Generic collisions

A large part of this book was dedicated to finding the most efficient way of determining whether two shapes intersect. The most robust, general purpose algorithm we have talked about so far has been Separating Axis Theorem (SAT). SAT has several limitations, the biggest one being curved surfaces. The execution time of SAT also gets out of hand when a complex mesh has many faces.

In this section, we will discuss a different generic algorithm--the Gilbert Johnson Keerthi or GJK algorithm. GJK runs in near linear time, often outperforming SAT. However, it is difficult to achieve the stability SAT provides using GJK. GJK should be used to find intersection data with complex meshes that have many faces. The GJK algorithm needs a support function to work, and this support function is called Minkowski Sum.

Note

For an algorithm to run in linear time, adding an iteration increases the execution time of the algorithm by the same amount every time, regardless of the size of the dataset. More information on runtimes is available online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Time_complexity.

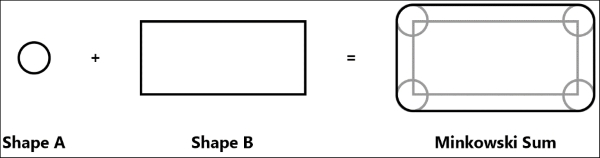

Minkowski Sum

The Minkowski Sum, also called Minkowski Addition, is an operation that we perform on two shapes; let's call them A and B. Given these input shapes, the result of the Minkowski Sum operation is a new shape that looks like shape A was swept along the surface of shape B. The following image demonstrates what this looks like:

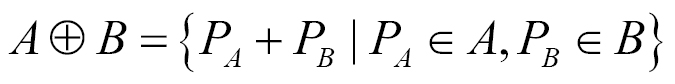

We can describe this operation as every point in the Minkowski Sum is a point from shape A added to a point from shape B. We can express this with the following equation:

Note

The preceding equation might be hard to read. The  symbol means element of and the

symbol means element of and the  symbol means the direct sum of two groups. We are defining how to take the direct sum of two shapes that might not have the same number of vertices.

symbol means the direct sum of two groups. We are defining how to take the direct sum of two shapes that might not have the same number of vertices.

This means that we find the Minkowski Sum of two shapes by adding all the vertices of each shape together. If we take object B and reflect it around the origin, we effectively negate B:

We often refer to taking the Minkowski Sum of A + (–B) as the Minkowski Difference because it can be expressed as (A – B). The Minkowski Difference produces what is called a Configuration Space Object or CSO.

If two shapes intersect, their resulting CSO will contain the origin of the coordinate system (0, 0, 0). If the two objects do not intersect, the CSO will not contain the origin.

This property makes the Minkowski Sum a very useful tool for generic collision detection. The shape of each object does not matter; so long as the CSO of the objects contains the origin, we know that the objects intersect.

Gilbert Johnson Keerthi (GJK)

Taking the Minkowski Difference of two complex shapes can be rather time consuming. Checking whether the resulting CSO contains the origin can be time consuming as well. The Gilbert Johnson Keerthi, or GJK, algorithm addresses these issues. The most comprehensive coverage of GJK is presented by Casey Muratori, which is available on the Molly Rocket website at https://mollyrocket.com/849.

The GJK algorithm, like the SAT algorithm, only works with convex shapes. However, unlike the SAT, implementing GJK for curved shapes is fairly easy. Any shape can be used with GJK so long as the shape has a support function implemented. The support function for GJK finds a point along the CSO of two objects, given a direction. As we only need an object in a direction, there is no need to construct the full CSO using the Minkowski Difference.

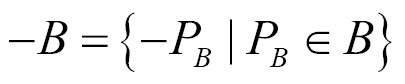

GJK is a fast iterative method; in many cases, GJK will run in linear time. This means for many cases, GJK is faster than SAT. GJK works by creating a simplex and refining it iteratively. A simplex is the generalized notion of a triangle in any arbitrary dimensions. For example, in two dimensions, a simplex is a triangle. In three dimensions, a simplex is a tetrahedron and in four dimensions, a simplex is a five cell. A simplex in k-dimensions will always have k + 1 vertices:

Once the simplex produced by GJK contains the origin, we know that we have an intersection. If the support point used to refine the simplex is further from the origin than the previous closest point, no collision has happened. GJK can be implemented using the following nine steps:

Initialize the (empty) simplex.

Use some direction to find a support point on the CSO.

Add the support point to the simplex.

Find the closest point in the simplex to the origin.

If the closest point is the origin, return a collision.

Else, reduce the simplex so that it still contains the closest point.

Use the direction from the closest point to origin to find a new support point.

If the new support is further from origin than the closest point, return no collision.

Add the new support to the simplex and go to step 4.

Expanding Polytope Algorithm (EPA)

The GJK algorithm is generic and fairly fast; it will tell us if two objects intersect. The information provided by GJK is enough to detect when objects intersect, but not enough to resolve that intersection. To resolve a collision, we need to know the collision normal, a contact point, and a penetration depth.

This additional data can be found using the Expanding Polytope Algorithm (EPA). A detailed discussion of the EPA algorithm is available on YouTube in the form of a video by Andrew at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6rgiPrzqt9w. Like the GJK, the EPA uses the Minkowski Difference as a support function.

The EPA algorithm takes the simplex produced by GJK as its input. The simplex is then expanded until a point on the edge of the CSO is hit. This point is the collision point. Half the distance from this point to the origin is the penetration depth. The normalized vector from origin to the contact point is the collision normal.

Using GJK and EPA together, we can get one point of contact for any two convex shapes. However, one point is not enough to resolve intersections in a stable manner. For example, a face to face collision between two cubes needs four contact points to be stable. We can fix this using an Arbiter, which will be discussed later in this chapter.