Now that we have our top level or the root window ready, it is time to think over a question—which components should appear in the window? In Tkinter jargon, these components are called widgets.

The syntax that is used to add a widget is as follows:

my_widget = Widget-name (its container window, ** its configuration options)

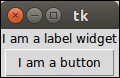

In the following example (1.02.py), we will add two widgets, a label, and a button to the root frame. Note how all the widgets are added between the skeleton code that we defined in the first example:

from tkinter import * root = Tk() label = Label(root, text="I am a label widget") button = Button(root, text="I am a button") label.pack() button.pack() root.mainloop()

The following is a description of the preceding code:

This code added a new instance named

labelfor the Label widget. The first parameter definedrootas its parent or container. The second parameter configured its text option asI am a label widget.Similarly, we defined an instance of a Button widget. This is also bound to the root window as its parent.

We used the

pack()method, which is essentially required to position the label and button widgets within the window. We will discuss thepack()method and several other related concepts when exploring the geometry management task. However, you must note that some sort of geometry specification is essential for the widgets to be displayed within the top-level window.

Running the preceding code will generate a window with a label and a button widget, as shown in the following screenshot:

Note the following few important features that are common to all widgets:

All widgets are actually objects derived from their respective widget classes. So, a statement such as

button = Button(its_parent)actually creates a button instance from theButtonclass.Each widget has a set of options that decides its behavior and appearance. This includes attributes such as text labels, colors, and font size. For example, the Button widget has attributes to manage its label, control its size, change its foreground and background colors, change the size of the border, and so on.

To set these attributes, you can set the values directly at the time of creating the widget, as demonstrated in the preceding example. Alternatively, you can later set or change the options of the widget by using the

.config()or.configure()method. Note that the.config()or.configure()methods are interchangeable and provide the same functionality. In fact, the.config()method is simply an alias of the.configure()method.

There are two ways to create widgets in Tkinter.

The first way involves creating a widget in one line and then adding the pack() method (or other geometry managers) in the next line, as follows:

my_label = Label(root, text="I am a label widget") my_label.pack()

Alternatively, you can write both the lines together, as follows:1

Label(root, text="I am a label widget").pack()

You can either save a reference to the widget created (my_label, as in the first example), or create a widget without keeping any reference to it (as demonstrated in the second example).

You should ideally keep a reference to the widget in case the widget has to be accessed later on in the program. For instance, this is useful in case you need to call one of its internal methods or for its content modification. If the widget state is supposed to remain static after its creation, you need not keep a reference to the widget.

Tip

Note that calls to pack() (or other geometry managers) always return None. So, consider a situation where you create a widget, save a reference to it, and add a geometry manager (say, pack()) on the same line, as follows:

my_label = Label(...).pack()

In this case, you are actually not creating a reference to the widget. Instead, you are creating a None type object for the my_label variable.

So, when you later try to modify the widget through the reference, you get an error because you are actually trying to work on a None type object.

If you need a reference to a widget, you must create it on one line and then specify its geometry (like pack()) on the second line, as follows:

my_label = Label(...) my_label.pack()

This is one of the most common errors committed by beginners.

Now, you will get to know all the core Tkinter widgets. You have already seen two of them in the previous example—the Label and Button widgets. Now, let's see all the other core Tkinter widgets.

Tkinter includes 21 core widgets, which are as follows:

|

Toplevel widget |

Label widget |

Button widget |

|

Canvas widget |

Checkbutton widget |

Entry widget |

|

Frame widget |

LabelFrame widget |

Listbox widget |

|

Menu widget |

Menubutton widget |

Message widget |

|

OptionMenu widget |

PanedWindow widget |

Radiobutton widget |

|

Scale widget |

Scrollbar widget |

Spinbox widget |

|

Text widget |

Bitmap Class widget |

Image Class widget |

Let's write a program to display all of these widgets in the root window.

The format used to add widgets is the same as the one that we discussed in the previous task. To give you an idea about how it's done, here's some sample code that adds some common widgets:

Label(parent, text="Enter your Password:") Button(parent, text="Search") Checkbutton(parent, text="Remember Me", variable=v, value=True) Entry(parent, width=30) Radiobutton(parent, text="Male", variable=v, value=1) Radiobutton(parent, text="Female", variable=v, value=2) OptionMenu(parent, var, "Select Country", "USA", "UK", "India", "Others") Scrollbar(parent, orient=VERTICAL, command= text.yview)

Can you spot the pattern that is common to each widget? Can you spot the differences?

As a reminder, the syntax for adding a widget is as follows:

Widget-name(its_parent, **its_configuration_options)

Using the same pattern, let's add all the 21 core Tkinter widgets into a dummy application (the 1.03.py code). We do not produce the entire code here. A summarized code description for 1.03.py is as follows:

We create a top-level window and a main loop, as shown in the earlier examples.

We add a Frame widget and name it

menu_bar. Note that Frame widgets are just holder widgets that hold other widgets. Frame widgets are great for grouping widgets together. The syntax for adding a frame is the same as that of all the other widgets:frame = Frame(root) frame.pack()

Keeping the

menu_barframe as the container, we add two widgets to it:Menubutton

Menu

We create another Frame widget and name it

frame. Keepingframeas the container/parent widget, we add the following seven widgets to it:Label

Entry

Button

Checkbutton

Radiobutton

OptionMenu

Bitmap Class

We then proceed to create another Frame widget. We add six more widgets to the frame:

Image Class

Listbox

Spinbox

Scale

LabelFrame

Message

We then create another Frame widget. We add two more widgets to the frame:

Text

Scrollbar

We create another Frame widget and add two more widgets to it:

Canvas

PanedWindow

All of these widgets constitute the 21 core widgets of Tkinter.

Now that you have had a glimpse of all the widgets, let's discuss how to specify the location of these widgets using geometry managers.