Databases

A database is a structured collection of data that helps manage information easily. A software layer called the Database Management System (DBMS) is used to store, maintain, and perform operations on the data. Databases are of two types, relational databases and non-relational databases.

Relational Databases

Relational databases or Structured Query Language (SQL) databases store data in a pre-determined structure of rows and columns called tables. A database can be made up of more than one such table, and these tables have a fixed structure of attributes, data types, and relations with other tables. For example, as we just saw in Figure 2.1, the book inventory table has a fixed structure of columns comprising Book Number, Author, Title, and Number of Copies, and the entries form the rows in the table. There could be other tables as well, such as Student Information and Lending Records, which could be related to the inventory table. Also, whenever a book is lent to a student, the records will be stored per the relationships between multiple tables (say, the Student Information and the Book Inventory tables).

This pre-determined structure of rules defining the data types, tabular structures, and relationships across different tables acts like scaffolding or a blueprint for a database. This blueprint is collectively called a database schema. When applied to a database, it will prepare the database to store application data. To manage and maintain these databases, there is a common language for relational databases called SQL. Some examples of relational databases are SQLite, PostgreSQL, MySQL, and OracleDB.

Non-Relational Databases

Non-relational databases or NoSQL (Not Only SQL) databases are designed to store unstructured data. They are well suited to large amounts of generated data that does not follow rigid rules, as is the case with relational databases. Some examples of non-relational databases are Cassandra, MongoDB, CouchDB, and Redis.

For example, imagine that you need to store the stock value of companies in a database using Redis. Here, the company name will be stored as the key and the stock value as the value. Using the key-value type NoSQL database in this use case is appropriate because it stores the desired value for a unique key and is faster to access.

For the scope of this book, we will be dealing only with relational databases as Django does not officially support non-relational databases. However, if you wish to explore, there are many forked projects, such as Django non-rel, that support NoSQL databases.

Database Operations Using SQL

SQL uses a set of commands to perform a variety of database operations, such as creating an entry, reading values, updating an entry, and deleting an entry. These operations are collectively called CRUD operations, which stands for Create, Read, Update, and Delete. To understand database operations in detail, let's first get some hands-on experience with SQL commands. Most relational databases share a similar SQL syntax; however, some operations will differ.

For the scope of this chapter, we will use SQLite as the database. SQLite is a lightweight relational database that is a part of Python standard libraries. That's why Django uses SQLite as its default database configuration. However, we will also learn more about how to perform configuration changes to use other databases in Chapter 17, Deployment of a Django Application (Part 1 – Server Setup). This chapter can be downloaded from the GitHub repository of this book, from http://packt.live/2Kx6FmR.

Data Types in Relational databases

Databases provide us with a way to restrict the type of data that can be stored in a given column. These are called data types. Some examples of data types for a relational database such as SQLite3 are given here:

INTEGERis used for storing integers.TEXTcan store text.REALis used for floating-point values.

For example, you would want the title of a book to have TEXT as the data type. So, the database will enforce a rule that no type of data, other than text data, can be stored in that column. Similarly, the book's price can have a REAL data type, and so on.

Exercise 2.01: Creating a Book Database

In this exercise, you will create a book database for a book review application. For better visualization of the data in the SQLite database, you will install an open-source tool called DB Browser for SQLite. This tool helps visualize the data and provides a shell to execute the SQL commands.

If you haven't done so already, visit the URL https://sqlitebrowser.org and from the downloads section, install the application as per your operating system and launch it. Detailed instructions for DB Browser installation can be found in the Preface.

Note

Database operations can be performed using a command-line shell as well.

- After launching the application, create a new database by clicking

New Databasein the top-left corner of the application. Create a database namedbookr, as you are working on a book review application:

Figure 2.2: Creating a database named bookr

- Next, click the

Create Tablebutton in the top-left corner and enterbookas the table name.Note

After clicking the

Savebutton, you may find that the window for creating a table opens up automatically. In that case, you won't have to click theCreate Tablebutton; simply proceed with the creation of the book table as specified in the preceding step. - Now, click the

Add fieldbutton, enter the field name astitle, and select the type asTEXTfrom the dropdown. HereTEXTis the data type for thetitlefield in the database:

Figure 2.3: Adding a TEXT field named title

- Similarly, add two more fields for the table named

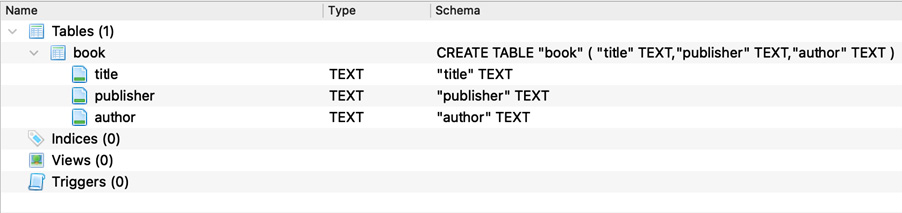

publisherandauthorand selectTEXTas the type for both the fields. Then, click theOKbutton:

Figure 2.4: Creating TEXT fields named publisher and author

This creates a database table called book in the bookr database with the fields title, publisher, and author. This can be seen as follows:

Figure 2.5: Database with the fields title, publisher, and author

In this exercise, we used an open-source tool called DB Browser (SQLite) to create our first database called bookr, and in it, we created our first table named book.