Decomposing problems

One of the most significant stumbling blocks, particularly when starting out, is breaking down a problem into smaller, more tractable parts. The tendency is to try to tackle the problem as a whole, rather than attempting to decompose it into smaller parts. There are two common reasons for this. The first is that the solver lacks confidence in their skills to correctly decompose. This is common among beginners. The second, which is more common among slightly more experienced solvers, is due to a fear of losing sight of the bigger picture. Obviously, one must keep track of the larger picture; a client would not accept a piece of software that solves one aspect of their problem but not the whole. A balance must be found between finding plausible routes to a solution without losing track of the overall problem.

Ideally, one would break down a problem into a number of isolated sub-problems, but generally this requires many steps of decomposition. Once you have sub-divided the problem several times, this might become the case, but generally, there will be dependencies between these sub-problems. These could be temporal dependencies – one problem must be solved before the other – or technical dependencies – where the solution to one problem depends on or is otherwise informed by the solution to (not the result of) another sub-problem. As the solver, you need to be wary of these constraints. Sometimes, embracing these interdependencies is key to finding a full solution.

Decomposing can also increase the overall complexity of the problem. Each stage of decomposition increases the number of items that must be incorporated back into the overall solution. This is not to say that these stages should be avoided, but it is something to keep in mind. Aim to decompose a problem as minimally as possible to avoid adding complexity and to make sure you don’t get too bogged down in the detail and lose track of the larger problem.

Some problems come with obvious decompositions, but this is not always the case. When this does happen, these easily defined sub-problems are almost always the best way to proceed. As you gain confidence and experience, more problems will start to look like this, and there will be more obvious divisions between parts of even complex problems.

Decomposing a simple thought experiment

Suppose you’re planning a dinner. The problem comes with already well-defined parts: the starter, main course, dessert, and drinks. Each of these is a specific problem to be solved, although they do have some weak linkages. (For example, the choice of main course will impact the choice of wine, which is a kind of technical dependency. Dinner is served after the starter, which is a temporal dependency. Both are weak, since one could technically order any wine with any main, and starters could be brought with mains.) If there are no complicating factors, such as specific dietary requirements, then each of these problems can be solved rather easily. In any case, these three parts will always need to be solved in some way or another in order to successfully deliver dinner to the guests.

To solve this problem, one might start by selecting the main course. Then one can select the starters and dessert courses (separately) to complement the mains. Finally, the drinks can be selected to complement each of the other components. In this way, we reduce the likelihood of having to backtrack because of incompatible course choices; the main course is the most important component, so solve this problem first.

General strategies for decomposing problems

Not all problems can be decomposed easily. Sometimes you must formulate an abstraction for a problem before you start trying to decompose it. Other times, the decomposition comes by recognizing that the problem is similar to some well-known class of problems. Usually, it will be a combination of both, along with a lot of trial and error. Over time, this process becomes easier, but it is never easy.

There are some general strategies for how to go about decomposing a problem, but there are often many “correct” decompositions. There is certainly a trade-off between finding the best decomposition versus finding a decomposition that is sufficient to solve the problem; don’t let perfect be the enemy of good. Ultimately, the most successful strategy is simple trial and error, taking obvious steps where they present themselves and relying on experience and similarity to other problems otherwise. Sometimes, you need to refine (or create) your abstractions before a pathway to decomposition appears.

A good way to start to collect parts of a problem together into coherent sub-problems is to ask reasonable questions about the problem or parts thereof: what is going to be the most difficult part of this problem; what information do I need for that part; do I need to apply any preprocessing to change the information before I can use it; do I need to apply any postprocessing to results before I return them to the user?

Most coding problems have at least three components. The first is acquiring the data from the user and converting it into a form that can be used. The second is doing the actual work required by the problem. The final step is performing any postprocessing and returning the results to the user. Sometimes this involves abstraction mechanisms made available through the programming language (e.g., classes).

Computing the average annual temperature differences

Let us assume that you have a database of regional temperature readings from around the world at regular intervals over many years. The problem in such a case is to compute the average year-on-year change in temperature in each region for each year. A very simple approach is to simply compute the average temperature of each region over each year, compute the difference from the previous year, and then collect these differences together. However, this does not quite capture the nuance of the problem.

The most difficult aspect of this problem is accounting for seasonal variation that occurs within the yearly cycle. Merely computing the differences between yearly averages would not account for this. A much better approach is to compute the difference between corresponding values within consecutive years and then average these differences over the whole year. However, even this isn’t perfect because it doesn’t account for short-term variability in temperature. A far better approach, provided we have enough data, is to compute an indicative temperature for a given period within the year. We can compute the average temperature within a short sliding window around the time in question to “smooth out” the volatility in local weather. These smoothed values should be broadly comparable year to year.

Another problem that might appear here, and in many similar problems, is whether all the measurements were taken with the same units: in many places, Celsius is the preferred unit of measurement for temperature, but in some places, Fahrenheit is the preferred unit. Many errors have been caused throughout history by failing to account for units of measurement, sometimes with catastrophic consequences. Ideally, all measurements should be converted to Kelvin (the SI unit for temperature on an absolute scale) before any computations are done.

To formulate a decomposition, we first look at the three high-level components. The first is loading and preprocessing data, which involves applying the conversion to Kelvin and placing the standardized data in a place where we can find it later (either on disk or in RAM, for instance). The second is doing the actual work of computing average differences. This will involve many sub-problems outlined above. The final high-level component is postprocessing the results to return to the user. For this problem, there is little, if any, postprocessing to be done, but sometimes this will be a significant step.

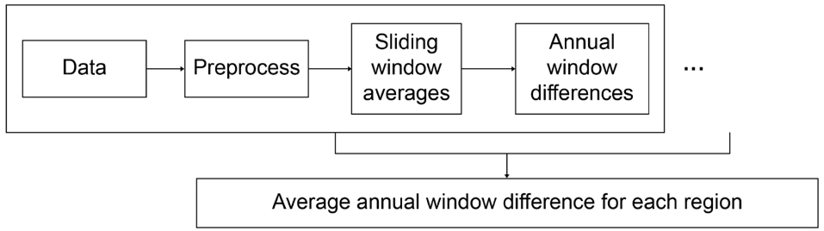

Computing the average regional differences is the main challenge. We have several sub-problems to solve here. A flow chart depicting the order of operations involved here is shown in Figure 1.1.

- For each source of data, we need to compute the averages over sliding windows of time over the whole year. None of these computations relies on any of the other computations, so they are a strong candidate for parallelization.

- We need to compute the annual differences between corresponding window averages. This can also be done in parallel.

- Finally, we need to average the window differences over each region for each pair of consecutive years.

Figure 1.1: Flow chart showing the order of sub-components of a regional weather comparison problem, including where the data has dependencies on previous steps and where solutions can be done in parallel

Now we have a reasonable understanding of the challenges that we will face in order to completely solve this problem. We have not yet made any attempt to actually solve these sub-problems. We don’t need to decompose further; each of the sub-problems already seems feasible without further decomposition. However, the option remains open to us should we need it.