Coupling and cohesion

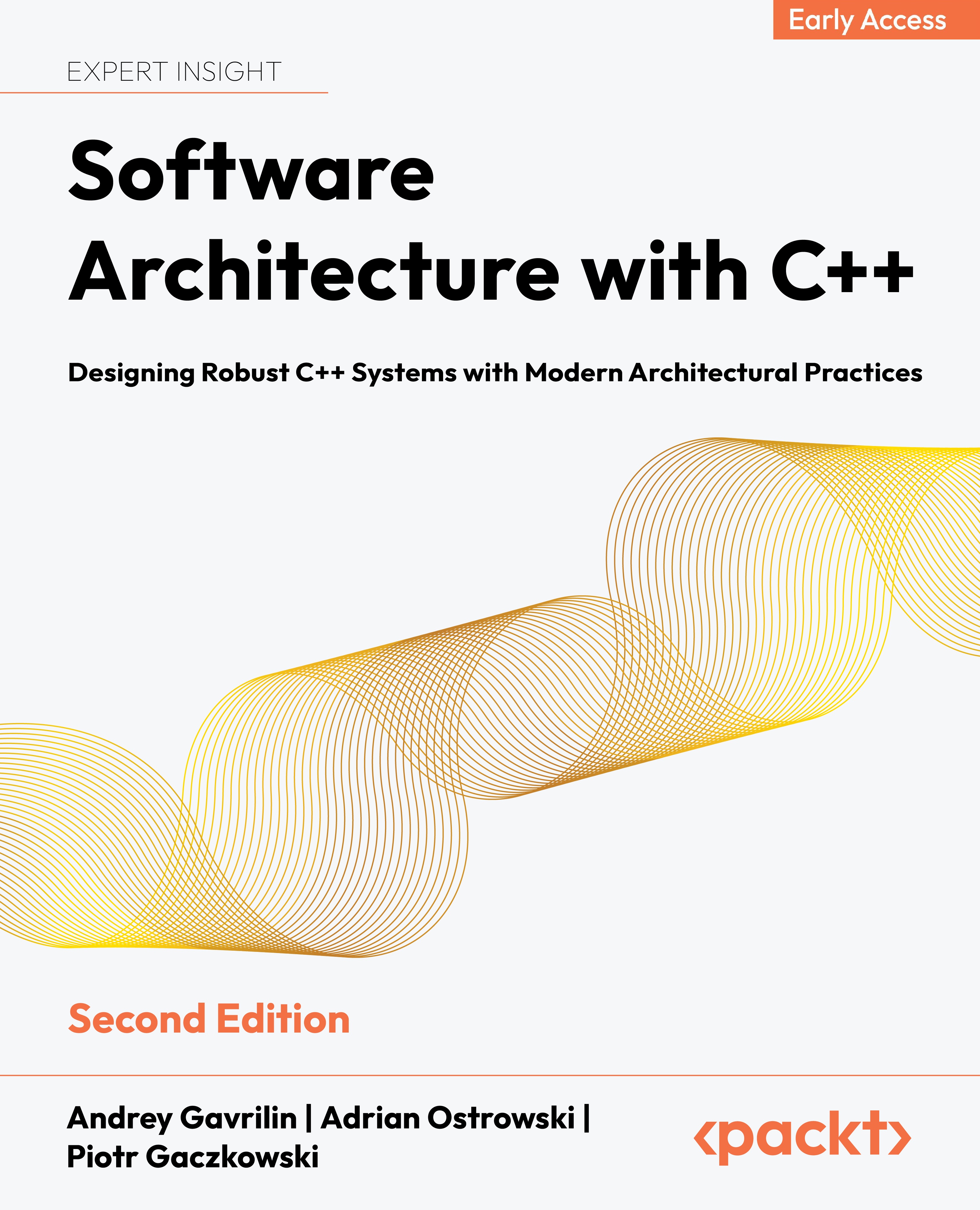

Low cohesion and high coupling are usually associated with software that's difficult to test, reuse, maintain, or even understand, so it lacks many of the quality attributes usually desired to have in software. Figure 1.2: Coupling versus cohesionThose terms often go together because often one trait influences the other, regardless of whether the unit we talk about is a function, class, module, library, service or even a whole system. To give an example, usually, monoliths are highly coupled and low cohesive, while distributed services tend to be at the other end of the spectrum.

Figure 1.2: Coupling versus cohesionThose terms often go together because often one trait influences the other, regardless of whether the unit we talk about is a function, class, module, library, service or even a whole system. To give an example, usually, monoliths are highly coupled and low cohesive, while distributed services tend to be at the other end of the spectrum.

Coupling

Coupling is a measure of how strongly one software unit depends on other units. A unit with high coupling relies on many other units. The lower the coupling, the better.An example of tightly coupled classes is the first implementation of the NotificationSystem and notifier classes while discussing the Dependency inversion topic. This principle reduces the degree of direct knowledge of modules about each other to reduce their coupling. Let's see what would happen if we were to add yet another notifier type:

class ChatNotifier {

public:

void sendMessage(const std::string &message) {

std::cout << "Chat channel: " << message << std::endl;

}

};

class NotificationSystem {

public:

void notify(const std::string &message) {

sms_.sendSMS(message);

email_.sendEmail(message);

chat_.sendMessage(message);

}

private:

SMSNotifier sms_;

EMailNotifier email_;

ChatNotifier chat_;

};It looks like instead of just adding the ChatNotifier class, we had to modify the public interface of the NotificationSystem class. This means they're tightly coupled and that this implementation of the NotificationSystem class actually breaks the OCP. For comparison, let's now see how the same modification would be applied to the implementation using dependency inversion:

class ChatNotifier {

public:

void notify(const std::string &message) { sendMessage(message); }

private:

void sendMessage(const std::string &message) {

std::cout << "Chat channel: " << message << std::endl;

}

};No changes to the NotificationSystem class were required, so now the classes are loosely coupled. All we needed to do was to add the ChatNotifier class. Structuring our code this way allows for smaller rebuilds, faster development, and easier testing, all with less code that's easier to maintain. To use our new class, we only need to modify the calling code:

using MyNotificationSystem =

NotificationSystem<SMSNotifier, EMailNotifier, ChatNotifier>;

auto sn = SMSNotifier{};

auto en = EMailNotifier{};

auto cn = ChatNotifier{};

auto ns = MyNotificationSystem{{sn, en, cn}};

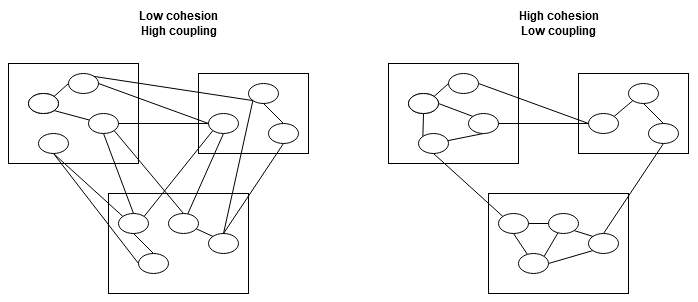

ns.notify("Azabeth Burns");This shows coupling on a class level. On a larger scale, for instance, if you're having a microservice architecture, a common pattern is to have multiple services use a shared database and communicate via this database. This causes high coupling between those services as you cannot freely modify the database schema without affecting all the microservices that use it. A better option is to have a database per service, wherein the low coupling can be achieved by introducing techniques such as message queueing, where services communicate by sending messages to a queue instead of calling each other. The services wouldn't then depend on each other directly, but just on the message format. However, having one database per service can be extremely expensive. Shared instance is a compromise pattern that helps solve the issue. Here, services must request data from other services via the API or other techniques because services must access only their parts of the data to loosen coupling. Figure 1.3: Microservices database design patternsLet's now move on to cohesion.

Figure 1.3: Microservices database design patternsLet's now move on to cohesion.

Cohesion

Cohesion is a measure of how strongly software elements belong together. In a system, the functionality offered by components in a module should be strongly related to make it highly cohesive.Consider the following example. It may seem trivial, but posting real-life scenarios, often hundreds if not thousands of lines long, would be impractical:

class CachingProcessor {

public:

Result process(WorkItem work);

Results processBatch(WorkBatch batch);

void addListener(const Listener &listener);

void removeListener(const Listener &listener);

private:

void addToCache(const WorkItem &work, const Result &result);

void findInCache(const WorkItem &work);

void limitCacheSize(std::size_t size);

void notifyListeners(const Result &result);

// ...

};We can see that our processor actually does three types of work and, therefore, violates SRP: the actual work, the caching of the results, and managing listeners. A common way to increase cohesion in such scenarios is to extract a class or even multiple ones:

class WorkResultsCache {

public:

void addToCache(const WorkItem &work, const Result &result);

void findInCache(const WorkItem &work);

void limitCacheSize(std::size_t size);

private:

// ...

};

class ResultNotifier {

public:

void addListener(const Listener &listener);

void removeListener(const Listener &listener);

void notify(const Result &result);

private:

// ...

};

class CachingProcessor {

public:

explicit CachingProcessor(ResultNotifier ¬ifier);

Result process(WorkItem work);

Results processBatch(WorkBatch batch);

private:

WorkResultsCache cache_;

ResultNotifier notifier_;

// ...

};Now each part is done by a separate, highly cohesive entity. Reusing them is now possible without much hassle. Even making them a template class should require little work. Last but not least, testing such classes should be easier as well.Putting this on a component or system level is straightforward – each component, service, and system you design should be concise and focus on doing one thing and doing it right. This concludes our introductory chapter. Let's now summarize what we've learned.