Developing architecture using Agile principles

Agile principles are concepts that encourage adaptability and efficiency in software development. The Agile Manifesto lists 12 guiding principles. You can refer to the link provided in the Further Reading section to read about the principles. Seemingly, architecture and Agile development methodologies are in an adversarial relationship, as there are many myths around Agile methodology; these are also mentioned in a resource linked at the end of the chapter. There are a few simple principles that you should follow in order to develop your product in an Agile way while still caring about its architecture.Agile, by nature, is iterative and incremental. This means preparing a big, upfront design is not an option in an Agile approach to architecture. Instead, a small, but still reasonable upfront design should be proposed. It's best if it comes with a log of decisions with the rationale for each of them. This way, if the product vision changes, the architecture can evolve with it. To support frequent release delivery, the upfront design should then be updated incrementally. Architecture developed this way is called evolutionary architecture.Thus, managing architecture doesn't require extensive documentation. In fact, documentation should cover only what's essential as this way it's easier to keep it up to date. It should be simple and cover only the relevant views of the system.Also, architect should not be considered as the single source of truth and the ultimate decision-maker. In Agile environments, it's the teams who are making decisions. Having said that, it's crucial that the stakeholders are contributing to the decision-making process – after all, their points of view shape how the solution should look.Nevertheless, an architect should remain part of the development team as often they're bringing strong technical expertise and years of experience to the table. They should also take part in making estimations, resolving conflicts over software architecture and planning the architecture changes needed before each iteration.In order for your team to remain Agile, you should think of ways to work efficiently and only on what's important. A good idea to embrace to achieve those goals is domain-driven design.

Domain-driven design

Domain-driven design (DDD) is a term introduced by Eric Evans in his book of the same title. In essence, it's about improving communication between business and engineering by bringing the developers' attention to the domain model that primarily consists of entities and their relationships. Aligning the implementation of the software with this model often leads to designs that are easier to understand and evolve together with the model changes.What has DDD got to do with Agile? Let's recall a part of the Agile Manifesto:

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools— The Agile Manifesto

Working software over comprehensive documentation

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

Responding to change over following a plan

So, how does DDD and Agile intersect? They have similar principles, which creates the basis for their integration:

- active stakeholder engagement: a ubiquitous language in DDD facilitates effective communication. Similarly, Agile focuses on collaboration.

- flexibility and adaptability: Agile embraces and implements changes, while DDD evolves the models to understand and represent domain specifics. Thus, both support dynamic environments.

- iterative development: Agile focuses on small incremental steps of software development, and DDD refines the models as they evolve. Thus, DDD aligns with the iterative nature of Agile as well as its tendency to avoid excessive documentation.

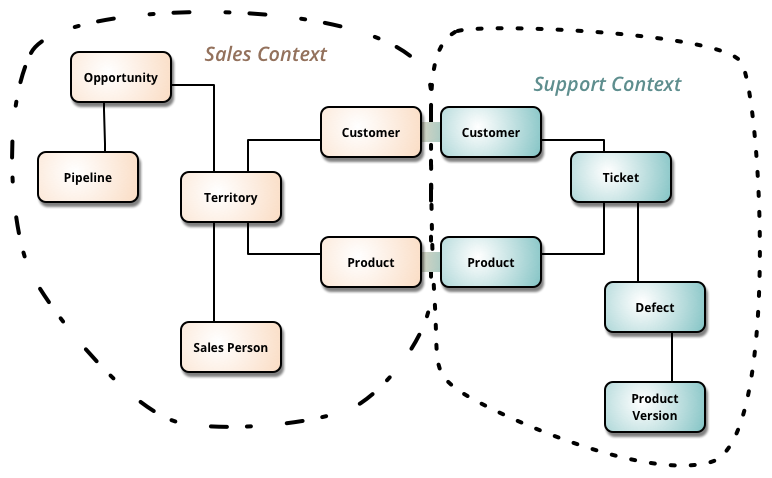

DDD and Agile complement each other and can provide better alignment with business requirements.In order to make the proper design decisions, you must understand the domain first. To do so, you'll need to talk to people a lot and encourage your developer teams to narrow the gap between them and businesspeople. The concepts in the code should be named after entities that are part of ubiquitous language. It's basically the common part of business experts' jargon and technical experts' jargon. Countless misunderstandings can be caused by each of these groups using terms that the other understands differently, leading to flaws in business logic implementations and often subtle bugs. Naming things with care and using terms agreed by both groups can improve the clarity of the project. Having a business analyst or other business domain experts as part of the team can help a lot here.If you're modeling a bigger system, it might be hard to make all the terms mean the same to different teams. This is because each of those teams really operates in a different context. DDD proposes the use of bounded contexts to deal with this. If you're modeling, say, an e-commerce system, you might want to think of the terms just in terms of a shopping context, but upon a closer look, you may discover that the inventory, delivery, and accounting teams actually all have their own models and terms.Each of those bounded contexts is a different subdomain of your e-commerce domain. Ideally, each subdomain can be mapped to its own bounded context managed by a dedicated team – a part of your system with its own vocabulary. Structuring teams around specific domains is consistent with Conway's Law described in the next chapter. It's important to set clear boundaries of such contexts when splitting your solution into smaller modules. When the boundaries are crossed, the domain models and terms may not remain relevant or acquire new meanings. Just like its context, each module has clear responsibilities, its own database schema, and its own code base. To help communicate between the teams in larger systems, you might want to introduce a context map, such as the one shown in Figure 1.1, which will show how the terms from different contexts relate to each other:

As you now understand some of the important project-management topics, we can switch to a few more technical ones.