“Computer, draw a robot!” said my young cousin to the first computer he had ever seen. (Since I had instructed it not to listen to strangers, the computer wasn’t receptive to this command.) If you’re like me, your first thought would be “how silly” or “how funny”—but this is a mistake. We’re being educated to accommodate computers, to compensate for the lack of ability of computers to understand humans, but in an ideal world that spoken command should have been enough to have the computer please my cousin.

This book doesn’t aim to teach you how to create software applications that intelligently interact with children—we’re still far from that point. However, we’ll help you make a small but important step in that direction. We’ll teach you how to use web development technologies available today—AJAX and ASP.NET AJAX in particular—to enhance web users’ experience of your web site, by creating more usable and friendly web interfaces. As far as this chapter is concerned, we’ll discuss the following topics:

The Big Picture. . Here we’ll answer a question we’re often asked: “Why bother improving our applications’ user interfaces and features, when the existing ones perform satisfactorily?”

Building Websites Since 1990. . What are the fundamental principles of the Web, and what are the important technologies that make it work? You probably know most of this, but we hope you’ll welcome this quick refresher.

The World of AJAX. . As you will learn (if you don’t already know), AJAX is a powerful tool that you can use to improve your web interfaces. However, it’s important to understand when you should use it, and when you should probably not. We’ll also discuss the basic principles of AJAX, and refer to online resources and tools that can help you along the way.

Setting Up Your Environment. . In this book you’ll find plenty of code—and you’ll probably be curious to execute it, and see it in action. We’ve taken care of that by including step-by-step instructions with every exercise. To avoid any potential problems following the exercises, in this section we walk you through the installation and configuration process for the software you need.

Hello World! . After reading so much pure theory, and installing many software packages (and we all know how boring software installation can be), you’ll probably be eager to write some code, so at the end of this chapter, you’ll write your first AJAX application.

Let’s get started. We hope your journey through this book will be a pleasant and useful one!

The story about Cristian’s 7-years old cousin—which happened back in 1990—is still relevant today, regarding the way people instinctively work with computers. The ability of technology to be user-friendly has evolved very much in the past years, but there’s still a long way until we have really intelligent computers that self-adapt to our needs. Until then, people need to learn how to work with computers—some to the extent that they end up loving a black screen with a tiny command prompt on it!

We will be very practical and concise in this book, but before getting back to your favorite mission—writing code—it’s worth taking a little step back, just to remember what we are doing and why we are doing it. We love technology to the sound made by each key stroke, so it’s very easy to forget that the very reason technology exists is to serve people and make their lives at home more entertaining, and at work more efficient.

The computer-working habits of many are driven by software with user interfaces that allow for intuitive (and enjoyable) human interaction. Not coincidentally, successful companies are typically one step ahead of their competition in offering their users simple and natural ways of achieving their goals. This probably explains the popularity of the mouse, of fancy features such as drag and drop, and of that simple text box that searches all the Web for you in just 0.1 seconds (or so it says).

Understanding the way people’s brains work would be the key to building the ultimate software application. While we’re far from that point, what we do understand is that end users need intuitive user interfaces; they don’t really care what operating system they’re running as long as the functionality they get is what they want. This is a very important detail to keep in mind, as programmers typically tend to think and speak in technical terms when interacting with end users. If you disagree, try to remember how many times you’ve said the word “database” when talking to a non-technical person.

The behavior of any computer software that interacts with humans is now even more important than it used to be, because nowadays the computer user base varies much more than in the past, when the users were technically sound as well. Now you need to display good looking reports to Cindy, the sales department manager, and you need to provide easy-to-use data entry forms to Dave, the sales person.

By observing people’s needs and habits while working with computer systems, the term software usability was born—referring to the art of meeting users’ interface expectations, understanding the nature of their work, and building software applications accordingly. AJAX in general, and the ASP.NET AJAX Framework in particular, are modern tools that web developers can use to develop user-friendly Web Applications. As with any other tool, however, they can be used improperly, complicating the user experience, neglecting users with disabilities, or lowering search engine performance.

This being a programming book, our strong focus will regard the technical aspects of Microsoft AJAX Library. However, as a responsible web developer, you should not lose sight of the complementary aspects that affect the success of a web application. If you haven’t already, we strongly recommend that you check at least some of these resources:

Don’t Make Me Think: A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability, second edition, by Steve Krug (New Riders Press, 2005)

Prioritizing Web Usability, by Jakob Nielsen and Hoa Loranger (New Riders Press, 2006)

Designing Interfaces: Patterns for Effective Interaction Design, by Jenifer Tidwell (O’Reilly, 2005)

Web Accessibility: Web Standards and Regulatory Compliance, by Andrew Kirkpatrick, Richard Rutter, Christian Heilmann, Jim Thatcher, and Cynthia Waddell (Friends of ED, 2006)

Ambient Findability, by Peter Morville (O’Reilly, 2005)

Bulletproof Web Design, second edition, by Dan Cederholm (New Riders Press, 2007)

Professional Search Engine Optimization with ASP.NET: A Developer’s Guide to SEO, by Cristian Darie and Jaimie Sirovich (Wrox Press, 2007)

Historically, building user-friendly software has always been easier with desktop applications than with web applications, simply because the Web lacked the technical tools to implement more complex features. Indeed, the Web was designed as a means of delivering simple documents formed of text, images, and links. However, as the Internet gets more mature, the technologies it supports become increasingly potent.

Many technologies have been developed—and are still being developed—to add flashy lights, accessibility, and power to web applications. Notable examples include Java applets, Flash, and Silverlight, which execute inside web browsers that have specific plugins installed. AJAX and ASP.NET AJAX have similar purpose, but on a different scale. They offer support for implementing lightweight rich internet applications without requiring additional plugins, while using a simpler programming model.

These days it’s increasingly harder to discuss AJAX without mentioning Web 2.0 (

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_2

). What is Web 2.0? Some say it is simply a marketing buzzword without any special meaning, while others use this term to describe the new open, interactive web that facilitates online information sharing and collaboration.

How did it start? In the words of Tim O’Reilly, who coined the term, Web 2.0 was born in 2004 after “a brainstorming session between O’Reilly and Medialive International”. As a result, a series of Web 2.0 conferences was born, and the term ended up gaining huge popularity.

Even today, we can find controversies about the definition of “Web 2.0”, but the version number is an obvious allusion to the recent changes of the World Wide Web. The initial goal of the Web addressed the delivery of static content in the form of text and images. The new generation of web applications tends to offer a richer user experience, much closer to that of desktop applications, while using live data from the Internet.

Initially, Web 2.0 was associated with the Semantic Web (

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semantic_web

). The Semantic Web is envisioned to be the next step in the Web’s evolution, based on online social-networking applications, using tag-based folksonomies (user-generated tags for data categorization). W3C director Tim-Berners Lee stated that “people keep asking what Web 2.0 is. I think maybe when you’ve got an overlay of scalable vector graphics - everything rippling and folding and looking misty - on Web 2.0 and access to a semantic Web integrated across a huge space of data, you’ll have access to an unbelievable data resource”.

Even if the services offered by Web 2.0 are far away from those aimed by the Semantic Web, where machines are able to understand and extract meanings from the content they offer, Web 2.0 still represents a step forward. In the world of Web 2.0 AJAX plays an essential role, offering the technological support for implementing rich and responsive Web interfaces.

The story about Cristian’s 7-years old cousin—which happened back in 1990—is still relevant today, regarding the way people instinctively work with computers. The ability of technology to be user-friendly has evolved very much in the past years, but there’s still a long way until we have really intelligent computers that self-adapt to our needs. Until then, people need to learn how to work with computers—some to the extent that they end up loving a black screen with a tiny command prompt on it!

We will be very practical and concise in this book, but before getting back to your favorite mission—writing code—it’s worth taking a little step back, just to remember what we are doing and why we are doing it. We love technology to the sound made by each key stroke, so it’s very easy to forget that the very reason technology exists is to serve people and make their lives at home more entertaining, and at work more efficient.

The computer-working habits of many are driven by software with user interfaces that allow for intuitive (and enjoyable) human interaction. Not coincidentally, successful companies are typically one step ahead of their competition in offering their users simple and natural ways of achieving their goals. This probably explains the popularity of the mouse, of fancy features such as drag and drop, and of that simple text box that searches all the Web for you in just 0.1 seconds (or so it says).

Understanding the way people’s brains work would be the key to building the ultimate software application. While we’re far from that point, what we do understand is that end users need intuitive user interfaces; they don’t really care what operating system they’re running as long as the functionality they get is what they want. This is a very important detail to keep in mind, as programmers typically tend to think and speak in technical terms when interacting with end users. If you disagree, try to remember how many times you’ve said the word “database” when talking to a non-technical person.

The behavior of any computer software that interacts with humans is now even more important than it used to be, because nowadays the computer user base varies much more than in the past, when the users were technically sound as well. Now you need to display good looking reports to Cindy, the sales department manager, and you need to provide easy-to-use data entry forms to Dave, the sales person.

By observing people’s needs and habits while working with computer systems, the term software usability was born—referring to the art of meeting users’ interface expectations, understanding the nature of their work, and building software applications accordingly. AJAX in general, and the ASP.NET AJAX Framework in particular, are modern tools that web developers can use to develop user-friendly Web Applications. As with any other tool, however, they can be used improperly, complicating the user experience, neglecting users with disabilities, or lowering search engine performance.

This being a programming book, our strong focus will regard the technical aspects of Microsoft AJAX Library. However, as a responsible web developer, you should not lose sight of the complementary aspects that affect the success of a web application. If you haven’t already, we strongly recommend that you check at least some of these resources:

Don’t Make Me Think: A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability, second edition, by Steve Krug (New Riders Press, 2005)

Prioritizing Web Usability, by Jakob Nielsen and Hoa Loranger (New Riders Press, 2006)

Designing Interfaces: Patterns for Effective Interaction Design, by Jenifer Tidwell (O’Reilly, 2005)

Web Accessibility: Web Standards and Regulatory Compliance, by Andrew Kirkpatrick, Richard Rutter, Christian Heilmann, Jim Thatcher, and Cynthia Waddell (Friends of ED, 2006)

Ambient Findability, by Peter Morville (O’Reilly, 2005)

Bulletproof Web Design, second edition, by Dan Cederholm (New Riders Press, 2007)

Professional Search Engine Optimization with ASP.NET: A Developer’s Guide to SEO, by Cristian Darie and Jaimie Sirovich (Wrox Press, 2007)

Historically, building user-friendly software has always been easier with desktop applications than with web applications, simply because the Web lacked the technical tools to implement more complex features. Indeed, the Web was designed as a means of delivering simple documents formed of text, images, and links. However, as the Internet gets more mature, the technologies it supports become increasingly potent.

Many technologies have been developed—and are still being developed—to add flashy lights, accessibility, and power to web applications. Notable examples include Java applets, Flash, and Silverlight, which execute inside web browsers that have specific plugins installed. AJAX and ASP.NET AJAX have similar purpose, but on a different scale. They offer support for implementing lightweight rich internet applications without requiring additional plugins, while using a simpler programming model.

These days it’s increasingly harder to discuss AJAX without mentioning Web 2.0 (

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_2

). What is Web 2.0? Some say it is simply a marketing buzzword without any special meaning, while others use this term to describe the new open, interactive web that facilitates online information sharing and collaboration.

How did it start? In the words of Tim O’Reilly, who coined the term, Web 2.0 was born in 2004 after “a brainstorming session between O’Reilly and Medialive International”. As a result, a series of Web 2.0 conferences was born, and the term ended up gaining huge popularity.

Even today, we can find controversies about the definition of “Web 2.0”, but the version number is an obvious allusion to the recent changes of the World Wide Web. The initial goal of the Web addressed the delivery of static content in the form of text and images. The new generation of web applications tends to offer a richer user experience, much closer to that of desktop applications, while using live data from the Internet.

Initially, Web 2.0 was associated with the Semantic Web (

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semantic_web

). The Semantic Web is envisioned to be the next step in the Web’s evolution, based on online social-networking applications, using tag-based folksonomies (user-generated tags for data categorization). W3C director Tim-Berners Lee stated that “people keep asking what Web 2.0 is. I think maybe when you’ve got an overlay of scalable vector graphics - everything rippling and folding and looking misty - on Web 2.0 and access to a semantic Web integrated across a huge space of data, you’ll have access to an unbelievable data resource”.

Even if the services offered by Web 2.0 are far away from those aimed by the Semantic Web, where machines are able to understand and extract meanings from the content they offer, Web 2.0 still represents a step forward. In the world of Web 2.0 AJAX plays an essential role, offering the technological support for implementing rich and responsive Web interfaces.

Before getting into the details of ASP.NET AJAX, let’s take the inevitable history lesson, to make sure we’ve got our definitions straight. We promise to keep this short. If you’re a web development veteran, feel free to skip ahead to “The World of AJAX” section.

Although the history of the Internet is a bit longer, 1991 is the year when Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP), which is still used to transfer data over the Internet, was invented. In its first few initial versions, it didn’t do much more than opening and closing connections. The later versions of HTTP (version 1.0 in 1996 and version 1.1 in 1999) became the protocols that we all know and use.

HTTP is supported by all web browsers, and it does very well the job it was conceived for—retrieving simple web content. Whenever you request a web page using your favorite web browser, the HTTP protocol is assumed. So, for example, when you type www.msn.com in the location bar of your web browser, it will assume by default that you meant

http://www.msn.com

.

The standard document type of the Web is Hypertext Markup Language (HTML), and it is built of markup that web browsers understand, parse, and display. HTML is a language that describes documents’ formatting and content, which is basically composed of static text and images. HTML wasn’t designed for building complex web applications with interactive content or user-friendly interfaces. When you need to get to another HTML page via HTTP, you need to initiate a full page reload, and the HTML page you requested must exist at the mentioned location, as a static document, prior to the request. It’s obvious that these restrictions don’t really encourage building anything interesting.

Nevertheless, HTTP and HTML are still very successful technologies that both web servers and web clients (browsers) understand. They are the foundation of the Web as we know it today. Figure 1-1 shows a simple transaction where a user requests a web page from the Internet using the HTTP protocol:

|

Figure 1-1. A Simple HTTP Request

Note

|

Three points for you to keep in mind here:

1. HTTP transactions always happen between a web client (the software making the request, such as a web browser) and a web server (the software responding to the request, such as Microsoft’s IIS [Internet Information Services]). From now on in this book, when saying ‘client’, we refer to the web client, and when saying ‘server’, we refer to the web server.

2. The user is the person using the client.

3. Even though HTTP (and its secure version, HTTPS) is arguably the most important protocol used on the Internet, it is not the only one. Web servers use different protocols to accomplish various tasks, usually unrelated to simple web browsing. The protocol that we’ll use most frequently in this book is HTTP, and when we say ‘web request’ we’ll assume a request using HTTP protocol, unless another protocol is mentioned explicitly.

The HTTP-HTML combination is very limited in what it can do by itself—it only enables users to retrieve static content (HTML pages) from the Internet. To complement the lack of features, several technologies have been developed.

All the web requests from now on in this book will use the HTTP protocol for transferring the data, but the data itself can be built dynamically on the web server (for example, using information from a database), and this data can contain more than plain HTML allowing the client to perform some functionality rather than simply display static pages.

The technologies that enable the Web to act smarter are grouped in the following two main categories:

Client-side technologies enable the web client to do more interesting things than displaying static documents. Usually these technologies complement HTML rather than replacing it entirely.

Server-side technologies are those that enable the server to store logic and build web pages on the fly. They usually have support for implementing complex logical, object-oriented programming, working with databases, and so on.

ASP.NET is Microsoft’s server-side web development technology, offering a solid development platform. It has many competitors, such as PHP, Java Server Pages (JSP), Perl, ColdFusion, Ruby on Rails, and others, each of them having their own sets of weaknesses and strengths.

ASP.NET is part of the .NET Framework. Since .NET’s initial release Microsoft’s marketing team have come up with more definitions for it, but for our purposes, the .NET Framework is the core technology that allows developing and executing ASP.NET Web Applications.

Figure 1-2 shows a request for a ASP.NET page called Default.aspx. This time, instead of sending back the contents of Default.aspx, the server executes Default.aspx, and sends back the results. These results must still be in the form of HTML, or in another format that the client understands.

|

Figure 1-2 Client Requests an ASP.NET Page

To write the server-side code for ASP.NET web pages, you can use a number of programming langages, C# and VB.NET being the most popular. In this book we’ll use C#, but if you’re a VB.NET fan you should be able to easily translate the code. Since both C# and VB.NET work using the base functionality packaged in the .NET Framework, the major difference between these languages is the syntax.

Note

|

Since you’re reading this book, you’re probably already familiar with ASP.NET. Should you need further guidance, you can check out Cristian’s Build Your Own ASP.NET 2.0 Web Site Using C# & VB (Sitepoint, 2006).

However, even with ASP.NET that can build custom-made database-driven responses, the browser still displays a static, boring, and not very smart web document. The need for smarter and more powerful functionality on the web client generated a separate set of technologies, called client-side technologies. Today’s browsers know how to parse more than simple HTML. Let’s see how.

The various client-side technologies differ in many ways, starting with how they get loaded and executed by the web client (web browser). JavaScript is a scripting language, whose code is written in plain text and can be embedded into HTML pages to empower them. When a client requests an HTML page, that HTML page may contain JavaScript. JavaScript is supported by all modern web browsers without requiring users to install new components.

JavaScript is a language in its own right (theoretically it isn’t tied to web development), it’s supported by most web browsers under any platform, and it has object-oriented capabilities. However, JavaScript’s OOP support doesn’t follow the same paradigm you’re used to from typical ASP.NET coding—but more on this later. JavaScript is not a compiled language so it’s not suited for intensive calculations or writing device drivers, and it must arrive in one piece at the client to be interpreted. This doesn’t make it suited for writing sensitive business logic (this wouldn’t be a recommended practice anyway), but it does a good job when used in web pages.

With JavaScript, developers could finally build web pages with snow falling over them (remember the days?), with client-side form validation so that the user won’t cause a whole page reload (incidentally losing all typed data) if he or she forgot to enter all the required fields (such as password, or credit card number), or if the email address had an incorrect format. However, despite its potential, JavaScript was never used consistently to make the web experience truly user-friendly, like a desktop application.

Other popular technologies that perform functionality at the client side are Java applets and Macromedia Flash. Java applets are written in the popular and powerful Java language, and are executed through a Java Virtual Machine that needs to be installed separately on the system. Java applets are certainly the way to go for more complex projects, but they have lost the popularity they once had over web applications because they consume many system resources. Sometimes they even need long startup times, and are generally too heavy and powerful for the small requirements of simple web applications.

Macromedia Flash has very powerful tools for creating animations and graphical effects, and it’s the de-facto standard for delivering such kind of programs via the Web. Flash also requires the client to install a browser plug-in. Flash-based technologies become increasingly powerful, and new ones keep appearing.

At the time of writing this book Microsoft is preparing for the launch of Silverlight, a competitor to both Java applets and Flash. Silverlight applications execute inside the web browser though a lightweight version of the .NET Framework supported through browser plugins.

With all these options for developing powerful features inside web browsers, why would anyone want anything new? What’s been missing?

As pointed out at the beginning of this chapter, technology exists to serve market needs. And part of the market wants more powerful functionality to web clients without using Flash, Java applets, or other technologies that are considered either too flashy or heavy-weight for certain purposes. A typical example is that of interactive form validation, where the data typed by the visitor must be checked against some validation rules coded on the server for compliancy.

For such scenarios, developers have usually created websites and web applications using HTML, JavaScript, and ASP.NET (or another server-side technology). The typical request with this scenario is shown in Figure 1-3, which shows an HTTP request, and a response made up of HTML and JavaScript built programmatically with ASP.NET.

|

Figure 1-3 HTTP, HTML, ASP.NET, and JavaScript in Action

The hidden problem with this scenario is that each time the client needs new data from the server, a new HTTP request must be made to reload the page, freezing the user’s activity. The page reload is the problem in the present day scenario, and AJAX comes to our rescue.

AJAX is an acronym for Asynchronous JavaScript and XML. If you think it doesn’t say much, we agree. Simply put, AJAX can be read “empowered JavaScript”, because it essentially offers a technique for client-side JavaScript to make background server calls and retrieve additional data as needed, updating certain portions of the page without causing full page reloads. The next figure offers a visual representation of what happens when a typical AJAX-enabled web page is requested by a visitor.

|

Figure 1-4 A Typical AJAX Call

When put into perspective, AJAX is about reaching a better balance between client functionality and server functionality when executing the action requested by the user. Up until now, client-side functionality and server-side functionality were regarded as separate bits of functionality that work one at a time to respond to user’s actions. AJAX comes with the solution to balance the load between the client and the server by allowing them to communicate in the background while the user is working on the page.

To explain with a simple example, consider web registration forms where the user is asked to write some data (such as name, e-mail address, password, credit card number, etc) that has to be validated before being used by the server-side code of your application. There are three important ways to implement this:

1. Let the user type all the required data, let him or her submit the page, and perform the validation on the server. If the validation doesn’t succeed, the server sends back the form, asking the visitor to correct the invalid entries. In this scenario the user experiences a dead time after submitting the form, while waiting for the new page to load.

2. Do the validation at the client side, using JavaScript. This way, the user is told about invalid data, and he or she can correct the invalid entires, before submitting the form. However this technique only works for very simple validation that doesn’t require additional data from the server while the user is filling the form in. Also, it doesn’t work with proprietary or secret validation algorithms that can’t be transferred to the client in the form of JavaScript code.

3. Use AJAX form validation so that the web application can validate the entered data by making server calls in the background, while the user keeps typing. For example, after the user types the first letter of the city, the web browser calls the server to load the list of cities that start with that letter, without interrupting the user’s current activity.

The situations where AJAX can make a difference are endless. Here are just a few of them:

Windows Local Live (

http://local.live.com): Microsoft maps service equivalent to other similar services offered by Google (Google Maps –http://maps.google.com) and Yahoo (Yahoo Maps –http://maps.yahoo.com).Flickr (

http://flickr.com/): “the best way to store, search, sort and share your photos”.PageFlakes (

http://pageflakes.com): “your personalized start page with news, photos, music, bookmarks, blogs, weather and much more”.Google Suggest (

http://www.google.com/webhp?complete=1): a Google query autocompletion feature that helps you with your Google searches. Similar functionality is offered by Yahoo! Instant Search, accessible athttp://instant.search.yahoo.com/.GMail (

http://www.gmail.com): a very popular service by now and doesn’t need any introduction. Other web-based email services such as Yahoo! Mail and Hotmail have followed this trend and offer AJAX-based interfaces.Digg (

http://www.digg.com): This is a hugely popular social bookmarking website featuring community-powered content.

So AJAX is about creating more versatile and interactive web applications by enabling web pages to make asynchronous calls to the server transparently while the user is working. AJAX is a tool that web developers can use to create smarter web applications that behave better than traditional web applications when interacting with humans.

The technologies AJAX is made of are already implemented in all modern web browsers, such as Mozilla Firefox, Internet Explorer, Opera, or Safari, so the client doesn’t need to install any extra modules to run an AJAX website. AJAX is made up of the following:

JavaScript is the essential ingredient of AJAX, allowing you to build the client-side functionality. In your JavaScript functions you’ll make heavy use of the Document Object Model (DOM) to manipulate parts of the HTML page.

The XMLHttpRequest object enables JavaScript to access the server asynchronously, so that the user can continue working, while functionality is performed in the background. Accessing the server just involves a simple HTTP request for a file or script located on the server. HTTP requests are easy to make and don’t cause any firewall-related problems.

Except for the simplest applications, a server-side technology is required to handle requests that come from the JavaScript client. In this book, we’ll use ASP.NET to perform the server-side part of the job.

Note

|

None of the AJAX components is new, or revolutionary (or even evolutionary) as the current buzz around AJAX might suggest. The newest AJAX component is XMLHttpRequest, which was released by Microsoft in 1998. The name “Ajax” was born in 2005, in Jesse James Garret’s article at

http://www.adaptivepath.com/publications/essays/archives/000385.php

, and gained much popularity when used by Google in many of its applications. You can read more on the history of AJAX at

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AJAX

.

What’s new with AJAX is that, for the first time, there is enough energy in the market to encourage standardization and define a clear direction of evolution. As a consequence, many AJAX frameworks are being developed, and many AJAX-enabled websites have appeared. Microsoft through its ASP.NET AJAX project is pushing AJAX development as well.

For client-server communication, the JavaScript client code and the ASP.NET server-side code need a way to pass data and understand that data. Passing the data is the simple part. The client script accessing the server (using the XMLHttpRequest object) can send name-value pairs using GET or POST. It’s very simple to read these values with any server script.

The server script simply sends back the response via HTTP, but unlike with a usual website, the response will be in a format that can be simply parsed by the JavaScript code on the client. The two popular formats are XML and JavaScript Object Notation (JSON), both of which will be introduced in Chapter 3.

This book assumes that you are already familiar with the AJAX ingredients, except maybe the XMLHttpRequest object, which is less popular. However, to make sure that we’re all on the same level, we’ll have a look together at how these pieces work, and how they work together, in Chapter 2. Until then, for the remainder of this chapter we’ll focus on the big picture, and we will write an AJAX program for the joy of the most impatient readers.

As noted earlier, AJAX can improve your visitors’ experience with your web site, but it can also worsen it when used inappropriately. In the vast majority of cases, AJAX is best used in addition to the traditional web development paradigms, rather than changing or replacing them.

For example, unless your application has really special requirements, it’s wise to let your users navigate your content using the good, old hyperlinks. Web browsers have a long history of dealing with content navigation, and web users have a long history of using browsers’ navigational features.

Let’s quickly review the potential benefits AJAX can bring to your projects:

It makes it possible to create better and more responsive web applications.

It encourages the development of patterns and frameworks, such as ASP.NET AJAX, that help developers avoid re-inventing the wheel when performing common tasks.

It makes use of existing technologies and features supported by all modern web browsers.

It makes use of many existing developer skills.

Potential problems with AJAX are:

Using AJAX for the wrong purposes. Increased awareness of usability, accessibility, web standards and search engine optimization will help you make better decisions when designing and implementing web sites.

You can’t easily allow for bookmarking AJAX-enabled pages. Typically AJAX applications run inside a web page whose URL doesn’t change in response to user actions, in which case you can only bookmark the entry page. It is possible to enable bookmarking by dynamically adding page anchors using your JavaScript code, such as in

http://www.example.com/my-ajax-app.html#Page2. You also need to create supporting code that loads and saves the state of your application through the anchor parameter.The Back and Forward buttons in browsers don’t produce the same result as with classic web sites, unless your AJAX application is programmed to support loading and saving states.

Search engines cannot index content dynamically generated by JavaScript in an AJAX application, because they don’t execute any JavaScript code when indexing the web site. If search engine optimization is important for your web site, you shouldn’t use AJAX for content delivery and navigation.

JavaScript can be disabled at the client side, which makes the AJAX application non-functional.

To enable AJAX page bookmarking and the Back and Forward browser buttons, you can use frameworks such as Really Simple History by Brad Neuberg (

http://codinginparadise.org/projects/dhtml_history/README.html

), or Nikhil Kothari’s UpdateHistory control for ASP.NET AJAX (

http://www.nikhilk.net/UpdateControls.aspx

).

Following the popularity of AJAX, a large numbers of AJAX-enabled frameworks and toolkits have been developed, including common features and offering great, tested features. Max Kiesler (

http://www.maxkiesler.com/

) has put a list of such products on his weblog, but in reality there are many more. Some are server-agnostic, while others are specifically created for ASP.NET, Java, PHP, Coldfusion, Flash and Perl backends. Among the most popular server-agnostic toolkits are Dojo (

http://dojotoolkit.org

), Prototype (

http://prototype.conio.net), and script.aculo.us (

http://script.aculo.us

).

As far as ASP.NET developers are concerned, their main choice—strongly promoted by Microsoft—is ASP.NET AJAX. Another popular choice is Ajax.NET Professional—developed by Michael Schwartz (

http://www.ajaxpro.info

).

ASP.NET AJAX (

http://ajax.asp.net/

), initially known only by its code name, Atlas, is a powerful AJAX framework written by Microsoft for ASP.NET developers. ASP.NET AJAX includes a wealth of tested functionality allowing you to build solid, cross-browser AJAX-based interfaces.

ASP.NET AJAX is a complex framework which includes AJAX-enabled ASP.NET server controls, as well as a very powerful client-side library. The native integration with Visual Studio .NET 2005 allows the developer to build rich internet applications (RIA) that are built upon the .NET 2.0, .NET 3.0, and .NET 3.5 frameworks without forcing the end user to have anything installed on the client.

The world of ASP.NET AJAX is composed of:

1. Microsoft AJAX Library. This is a powerful client-side Javascript library that offers a common API for all modern browsers, and supports any backend web technology. In theory at least, you can use the Microsoft AJAX Library with a PHP or Java server script. In practice, the Microsoft AJAX Library is really meant to be used togehter with its server-side companion from the ASP.NET AJAX Extensions. Keep an eye on Jay Kimble’s Java integration project for Microsoft AJAX Library at

http://www.codeplex.com/dtajax/, and on the PHP integration athttp://www.codeplex.com/phpmsajax.2. ASP.NET AJAX Extensions includes the Microsoft AJAX Library, and also a set of server-side AJAX-enabled controls that integrate well with that library (

ScriptManager,UpdatePanel,Timer,UpdateProgress, andAsyncPostbackTrigger). At installation the product integrates with Visual Studio 2005 so that you can access its controls through the Visual Studio Toolbox, and will be included into the next version of Visual Studio, which at the time of writing this book is code-named Orcas.3. The ASP.NET AJAX Control Toolkit is a set of free, shared source controls and components that help you get the most value from the ASP.NET AJAX Extensions. At the time of writing this book, the control toolkit is still under development, and it isn’t part of the 1.0 release of ASP.NET AJAX. However, it will ship together with Visual Studio “Orcas”.

This book is dedicated to the first of these three parts of ASP.NET AJAX. We’ll cover the Microsoft AJAX Library in detail, and by end of it you’ll be able to masterfully use its features at their full potential.

Note

|

The Microsoft AJAX Library is the kind of technology that’s easy to start with, but as you dwelve into its details, you’ll notice that its complexity requires a longer learning curve than you may expect. In our opinion, there aren’t any real shortcuts to this process: you need to understand the foundations of this framework very well before you can be efficient with it.

Understanding the Microsoft AJAX Library also requires a good knowledge of JavaScript and its object-oriented model. In theory, working with an API only requires knowledge of that API’s publicly exposed features. In practice however, dealing with a JavaScript framework—especially one that is young and sometimes imperfect—frequently requires an understanding of the details of its inner workings. Sooner or later, you’ll be tempted to open the source code of the Microsoft AJAX Library. This is not something that you’d expect from a C# library, but we’re dealing with a different kind of “monster” here.

The first part of this book will cover the basics of AJAX with JavaScript and ASP.NET, without involving the Microsoft AJAX Library. You will find that you can implement simple AJAX features by hand, simply coding the necessary asynchronous server calls yourself. Then we’ll set the ground for ASP.NET AJAX by teaching the more advanced features of JavaScript, such as prototypes and closures.

If you already understand the theory of JavaScript and its interaction with ASP.NET, feel free to skip to Chapter 4. However, we advise you to look at Chapters 2 and 3 so that we’re on the same level when we meet again in Chapter 4.

Finally, here are a few places that may help you in your journey into the exciting world of AJAX. For starters, here are a few useful generic AJAX resources:

http://www.ajaxian.comis the AJAX website of Ben Galbraith and Dion Almaer, the authors of Pragmatic Ajax (Pragmatic Bookshelf, 2006).http://ajaxpatterns.orgis an informative website about AJAX design patterns, and the home page of Ajax Design Patterns by Michael Mahemoff (O’Reilly, 2006).http://www.fiftyfoureleven.com/resources/programming/xmlhttprequestis a comprehensive collection of articles about AJAX.http://www.sitepoint.com/subcat/javascriptis Sitepoint’s AJAX home, featuring some excellent articles.http://developer.mozilla.org/en/docs/AJAXis Mozilla’s page on AJAX.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ajaxis the Wikipedia page on AJAX.

This list is by no means complete. If you need more online resources, search engines will surely be available for help. For specific information on ASP.NET AJAX and related technologies, we recommend that you visit the following resources from time to time—ideally by subscribing to their RSS or Atom feeds:

|

Blogger or Resource Name |

URL |

|---|---|

|

Atlas team | |

|

Dino Esposito | |

|

Eilon Lipton | |

|

Alessandro Galo | |

|

Jay Kimble | |

|

Luis Abreu | |

|

Nikhil Kothari | |

|

Steve Marx |

In the next few pages we’ll guide you through installing the following softwares, which you’ll need for this book:

1. IIS (Internet Information Services), which is the Web Server used to serve ASP.NET pages.

2. Visual Web Developer 2005 Express Edition, which is the tool that you’ll be using to develop your ASP.NET applications.

3. The ASP.NET AJAX Framework.

To run ASP.NET web applications, you can use either Visual Web Developer’s integrated Web server (Cassini), or you can use IIS. Theoretically, the most important difference between the two environments are the credentials under which the code runs. Cassini runs with the credentials of the logged in user, while IIS uses a special system account named ASPNET.

Note

|

If you really want to, you can also run ASP.NET pages using Apache, although we’ve not tested this configuration for the purposes of this book. Read more details at

http://weblogs.asp.net/israelio/archive/2005/09/11/424852.aspx

.

The two major benefits of using Cassini are:

Cassini works on systems that don’t ship with IIS, such as Windows XP Home Edition.

Cassini can be used in case you don’t want to use your main IIS Web Server for development purposes.

Even if these advantages don’t convince you, we still recommend using IIS because your application would end up running under an IIS server anyway, so the development environment would more closely resemble the production environment.

IIS is delivered with most versions of server-capable Windows operating systems, including Windows Vista Business, Windows XP Professional, Windows XP Media Center Edition, Windows 2000 Professional, Server, Advanced Server, and Windows Server 2003, but it’s not installed automatically in all versions, which is why it may not be present on your computer.

IIS isn’t available in Windows XP Home Edition, Windows Vista Home Basic, or Windows Vista Home Premium—if you run one of these, you’ll need to rely on Cassini.

Note

|

The main development tool we’ll use in this book is Visual Web Developer 2005, which works best with IIS 6, which ships with Windows XP. Windows Vista, on the other hand, includes IIS 7, whose default settings aren’t very friendly with Visual Web Developer 2005. This explains that you have more configuration work to do before you’ll be able to run and debug your ASP.NET Web Applications under Windows Vista properly.

To install IIS, simply follow these steps:

1. In the Control Panel, select Programs and Features (in Windows Vista), or Add or Remove Programs (in Windows XP).

2. Choose Turn Windows features on or off (in Windows Vista), or Add/Remove Windows Components (in Windows XP). The list of components will become visible within a few seconds.

3. In the list of components, check Internet Information Services. If running Windows XP, expand the node and make sure that the IIS Frontpage Extensions node is checked.

In Windows Vista, also select the following options (also see Figure 1-4).

1. Web Management Tools | IIS 6 Management Compatibility node, and its IIS Metabase and IIS 6 configuration compatibility sub-node. (IIS 6 Management Compatbility is required by Visual Web Developer 2005 when connecting to your web site through FrontPage Extensions.)

2. World Wide Web Services | Application Development Features | ASP.NET node.

3. Select the World Wide Web Services | Security | Windows Authentication node, which is necessary if you want to run applications in debug mode.

Figure 1-5 Configuring IIS 7 Options in Windows Vista

4. Click Next or OK. Windows may prompt you to insert the Windows CD or DVD.

To administer IIS, you use the Internet Information Services (IIS) Manager tool (in Windows Vista) or the Internet Information Services tool (in Windows XP) that you can find in the Administrative Tools menu of the Control Panel.

Install Visual Web Developer 2005 Express Edition following these simple steps:

2. Click the Download link. You’ll download a file named

vwdsetup.exe.3. Execute the downloaded file.

4. Accept the default options. At one point you’ll be asked about installing Microsoft MSDN 2005 Express Edition, which is the product’s documentation. Installing it will do no harm, but you need to be patient, because it’s quite big.

5. Install the Visual Web Developer Service Pack 1. If you use Windows Vista, you should install the Service Pack 1 for Windows Vista.

6. The final step involves configuring ASP.NET with IIS. If you’ll be using Cassini or IIS 7, this step is not needed. Start a command-line console (Start | Run | cmd), and type the following commands:

cd C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v2.0.50727 aspnet_regiis.exe -i

To keep your hard drive tidy, let’s create a folder that we’ll be using for every exercise in this book. Create a folder named Atlas in an easily accessible place of your hard drive. I’ll assume you’re creating it as C:\Atlas.

Now we need to configure this folder as an IIS virtual directory so that it doesn’t interfere with other applications you may have on your machine. After preparing the Atlas Web Application, the http://localhost/Atlas/ application will be loaded from the C:\Atlas physical folder. If you can’t use IIS, then skip to the “Hello World!” section, a bit later in this chapter.

Because of the interface differences between the IIS 5/6 and IIS 7, separate installation instructions are provided for Windows XP and Windows Vista.

If you’re running Windows Vista and IIS 7, follow these steps to prepare your Atlas folder.

1. Open the IIS Manager tool from the Administrative Tools section of the Control Panel.

2. Find the Default Web Site in the Connections tab, and make sure it’s started. If its status is Stopped, right-click on it and select Start.

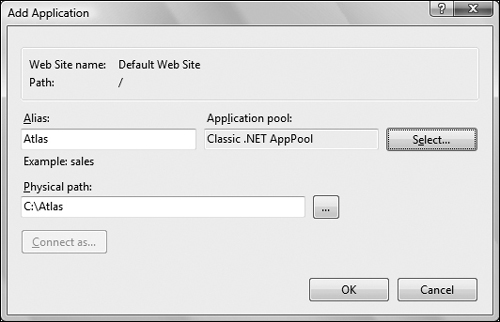

3. Right-click Default Web Site, and select Add Application from the context menu.

4. Choose Atlas for the alias name, and C:\Atlas for its “physical” path. Then click Select..., choose Classic .NET AppPool, and click OK. (If you don’t choose the Classic .NET AppPool, you won’t be able to debug the project using Visual Web Developer 2005.) In the end, the Add Application dialog should look like Figure 1-6.

Figure 1-6 Creating the Atlas IIS Application

5. After clicking OK to close the Add Application dialog, the Atlas virtual directory will show up as a child node under Default Web Site. Select the Atlas node, double-click the Authentication icon, and enable Windows Authentication.

6. Close the IIS Manager.

If you’re running Windows XP, follow these steps to prepare your Atlas folder

1. Open the Internet Information Services tool from the Administrative Tools section of the Control Panel. Then expand the node for your local computer, then expand the Web Sites node, as shown in Figure 1-7.

Figure 1-7 Internet Information Services Tool in Windows XP

2. Make sure that the Default Web Site is running. If its status is Stopped, right-click on it and select Start:

3. Right-click Default Web Site, and select New | Virtual Directory.

4. In the wizard that shows up, first click Next, then type Atlas for the name of the Virtual Directory. Then click Next.

5. Type the full path for the “physical” folder where you’ll save the examples from this book. If you created the folder as suggested, then the path whould be C:\Atlas.

6. In the next screen, check Read and Run scripts (such as ASP), and click Next.

7. Click Finish to close the wizard, then close the Internet Information Services applet.

ASP.NET AJAX is a powerful and exciting framework which comes with lot of built-in features, but in order to make the most out of it, it’s best to take a disciplined approach and learn the basics first. Chapter 2 and Chapter 3 will teach you the foundations, and how to implement basic AJAX features with ASP.NET without using the ASP.NET AJAX Framework. You’ll start using the Microsoft AJAX Library in Chapter 4.

This chapter ends with an exercise where we’ll build a simple AJAX application with ASP.NET, named Quickstart. This application doesn’t make use of any of the components of the Microsoft ASP.NET AJAX Framework. Instead, it uses simple JavaScript and C# code.

Note

|

Going through this exercise is optional. The exercise is for the most impatient readers willing to start coding as soon as possible, but it assumes you’re already familiar with JavaScript, ASP.NET, and XML. If this is not the case, or if at any time you feel this exercise is too challenging, feel free to skip to Chapter 2.

Quickstart is a simple AJAX form-validation application where the user is requested to type his or her name, and the server keeps verifying if it recognizes the typed name while the user is writing. Figure 1-8 shows the initial page, Quickstart.html, loaded by the user.

|

Figure 1-8 The Front Page of Your Quickstart Application

While the user is typing, the server is being called asynchronously, at regular intervals, to validate the current user input. The server is called automatically, approximately once per second, which explains why we don’t need a button (such as a Send button) to notify when we’re done typing. (This method may not be appropriate for real log-in mechanisms but it’s very good to demonstrate the basic AJAX functionality).

Depending on the entered name, the message from the server may differ; see an example in Figure 1-9.

|

Figure 1-9 User Receives a Prompt Reply From the Web Application

Check out this example online at

http://www.cristiandarie.ro/asp-ajax/Quickstart.html

. Maybe at first sight there’s nothing extraordinary going on there. We’ve kept this first example simple on purpose, to make things easier to understand. What’s special about this application is that the displayed message comes automatically from the server, without interrupting the user’s actions. (The messages are displayed as the user types a name.) The page doesn’t get reloaded to display the new data, even though a server call needs to be made to get that data. This wasn’t a simple task to accomplish using non-AJAX web development techniques. The application consists of the following three files:

Quickstart.htmlis the initial HTML file the user requests.Quickstart.jsis a file containing JavaScript code that is loaded on the client along withQuickstart.html. This file will handle making the asynchronous requests to the server, when server-side functionality is needed.Quickstart.aspxis an ASP.NET page residing on the server that gets called by the JavaScript code inQuickstart.jsfile from the client.

Figure 1-10 shows the actions that happen when running this application:

|

Figure 1-10 Diagram Explaining the Inner Works of Your Quickstart Application

Steps 1 through 5 are a typical HTTP request. After making the request, the user needs to wait until the page gets loaded. With typical (non-AJAX) web applications, such a page reload happens every time the client needs to get new data from the server.

Steps 5 through 9 demonstrate an AJAX-type call—more specifically, a sequence of asynchronous HTTP requests. The server is accessed in the background using the XMLHttpRequest object. During this period the user can continue to use the page normally, as if it were a normal desktop application. No page refresh or reload is experienced in order to retrieve data from the server and update the web page with that data.

Now it’s time to implement this code on your machine. Before moving on, ensure you’ve prepared your working environment as shown earlier in this chapter.

Note

|

All the exercises in this book assume that you’ve installed software on your machine as shown earlier in this chapter. If you set up your environment differently you may need to implement various changes, such as using different folder names, and so on.

1. Open Visual Web Developer, and select File | Open Web Site.

2. Select the Local IIS location, and the Atlas application, as shown in Figure 1-11. Then click OK.

Figure 1-11 Loading the Atlas Application in Visual Web Developer

3. Right-click the root node in Solution Explorer, and select Add New Item. Choose the HTML Page template, and type

Quickstart.htmlfor the name. Then click Add.4. Modify the HTML code generated for you like this:

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd"> <html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml"> <head> <title>AJAX with ASP.NET: Quickstart</title> <script type="text/javascript" src="Quickstart.js"></script> </head> <body onload="process()"> <div> Server wants to know your name: <input type="text" id="myName" /> </div> <div id="divMessage" /> </body> </html>5. Right-click the root node in Solution Explorer, then click Add New Item, and add a file named

Quickstart.jsusing the JScript File template. Then type the following code:// stores a reference to an XMLHttpRequest instance var xmlHttp = createXmlHttpRequestObject(); // retrieves the XMLHttpRequest object function createXmlHttpRequestObject() { // will store the reference to the XMLHttpRequest object var xmlHttp; // this should work for all browsers except IE6 and older try { // try to create XMLHttpRequest object xmlHttp = new XMLHttpRequest(); } catch(e) { // assume IE6 or older xmlHttp = new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP"); } // return the created object or display an error message if (!xmlHttp) alert("Error creating the XMLHttpRequest object."); else return xmlHttp; } // make asynchronous HTTP request using the XMLHttpRequest object function process() { // proceed only if the xmlHttp object isn't busy if (xmlHttp.readyState == 4 || xmlHttp.readyState == 0) { // retrieve the name typed by the user on the form name = encodeURIComponent(document.getElementById("myName"). value); // execute the Quickstart.aspx page from the server xmlHttp.open("GET", "Quickstart.aspx?name=" + name, true); // define the method to handle server responses xmlHttp.onreadystatechange = handleServerResponse; // make the server request xmlHttp.send(null); } else // if the connection is busy, try again after one second setTimeout("process()", 1000); } // executed automatically when a message is received from server function handleServerResponse() { // move forward only if the transaction has completed if (xmlHttp.readyState == 4) { // status of 200 indicates success if (xmlHttp.status == 200) { // extract the XML retrieved from the server xmlResponse = xmlHttp.responseXML; // obtain the root element of the XML structure xmlDocumentElement = xmlResponse.documentElement; // get the text message from the first child of the document helloMessage = xmlDocumentElement.firstChild.data; // display the data received from the server document.getElementById("divMessage").innerHTML = "<i>" + helloMessage + "</i>"; // restart sequence setTimeout("process()", 1000); } // a HTTP status different than 200 signals an error else { alert("There was a problem accessing the server: " + xmlHttp.statusText); } } }

6. Create a new file named

Quickstart.aspxin your project using the Web Form template. Choose Visual C# for the language, and make sure both the Place code in separate file and Select master page checkboxes are unchecked. While using code-behind files is a good idea in most cases, this time we don’t want to complicate things unnecessarily.7. Delete the template code generated by Visual Web Developer for you, and type the following code in

Quickstart.aspx:<script runat="server" language="C#"> protected void Page_Load() { // declare the names that are recognized by the server string[] names = new string[] { "CRISTIAN", "BOGDAN", "YODA" }; // retrieve the current name sent by the client string currentUser = Request.QueryString["name"] + ""; // set the response content type Response.ContentType = "text/xml"; // output the XML header Response.Write("<?xml version=\"1.0\" encoding=\"UTF-8\" standalone=\"yes\"?>"); Response.Write("<response>"); // if the name is empty... if (currentUser.Length == 0) { Response.Write("Stranger, please tell me your name!"); } // if the typed name is in the names array else if (Array.IndexOf(names, currentUser.ToUpper().Trim()) >= 0) { Response.Write("Hello, master " + currentUser + "!"); } // if the name is neither empty or recognized else { Response.Write(currentUser + ", I don't know you!"); } // output the XML document Response.Write("</response>"); // flush the response stream Response.Flush(); } </script>8. Double-click

Quickstart.htmlin Solution Explorer, and press F5 to execute the project in debug mode (You can also execute the project without debugging, by hitting CTRL+F5). Visual Web Developer will offer to enable debugging by creating aWeb.configfile with the appropriate settings for you, as shown in Figure 1-12. Click OK.

Figure 1-12 Visual Web Developer Offering to Enable Debugging

9. A browser window will load

http://localhost/Atlas/Quickstart.html, which should look like shown earlier in Figures 1-9 and 1-10.

Note

|

Should you encounter any problems running the application, check whether you correctly followed the installation and configuration procedures. Most errors happen because of small problems such as typos. In Chapter 2 you’ll learn how to implement error handling in your JavaScript and ASP.NET code.

Here comes the fun part—understanding what happens in that code. (Remember that we’ll discuss the technical details in the following chapters.)

Let’s start with the file the user first interacts with, Quickstart.html. This file references the mysterious JavaScript file called Quickstart.js, and builds a very simple web interface for the client.

In the following code snippet from Quickstart.html, notice the elements highlighted in bold:

<body onload="process()"> <div> Server wants to know your name: <input type="text" id="myName" /> </div> <div id="divMessage" /> </body>

When the page loads, a function from Quickstart.js called process() is executed. This somehow causes the <div> element to be populated with a message from the server. Before seeing what happens inside the process() function, let’s see what happens at the server side.

The server is represented by a page called Quickstart.aspx. This page receives the name typed by the visitor, and it replies with an XML message. You may want to have another look at Figure 1-10, which describes the process. This XML message Quickstart.aspx sends back to the client consists of a <response> element that packages the response message:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="yes"?> <response> ... message the server wants to transmit to the client ... </response>

If the user name received from the client is empty, the message will be, “Stranger, please tell me your name!”. If the name is Cristian, Bogdan, or Yoda, the server responds with “Hello, master <user name>!”. If the name is anything else, the message will be “<user name>, I don’t know you!”. So if Mickey Mouse types his name, the server will send back the following XML structure:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="yes"?> <response> Mickey Mouse, I don't know you! </response>

If you want to test this actually happens, it’s quite simple. The advantage of sending parameters from the client via GET is that it’s very simple to emulate such a request using your web browser, since GET simply means that you append the parameters as name/value pairs in the URL query string. So to simulate the server request done by the client when the user types Yoda, simply load http://localhost/Atlas/Quickstart.aspx?name=Yoda into your web browser. You should get the XML response shown in Figure 1-13.

|

Figure 1-13 The XML Data Generated by Quickstart.aspx

The Quickstart.aspx page contains a simple script that contains the Page_Load() method, which executes by default when the script is accessed. Page_Load() starts by declaring the array of strings that will be the names “known” by the server:

protected void Page_Load()

{

// declare the names that are recognized by the server

string[] names = new string[] { "CRISTIAN", "BOGDAN", "YODA" };Next, the Page_Load() method contains the entire server logic behind this example. It retrieves the name sent by the client:

// retrieve the current name sent by the client string currentUser = Request.QueryString["name"] + "";

The value of the name query string parameter is read using Request. QueryString["name"]. This returns null when name doesn’t exist in the query string, and we use a little trick—appending an empty string to it—to avoid errors when this happens. (In production code, when performance is a factor, you may prefer to use different error-avoiding techniques.)

Next, we set the content type of the response to text/xml, and we start building the XML response by opening the <response> element:

// set the response content type

Response.ContentType = "text/xml";

// output the XML header

Response.Write("<?xml version=\"1.0\" encoding=

\"UTF-8\" standalone=\"yes\"?>");

Response.Write("<response>");The Response.ContentType property corresponds to the Content-Type HTTP header. We use it to set the content type to text/xml, which is appropriate when the page sends back an XML structure. Response.Write() is used to send content to the output. The first bits we output are the XML document definition, and the <response> document element.

We continue by writing the message itself to the output. If the name is an empty string, the message will be “Stranger, please tell me your name!”

// if the name is empty...

if (currentUser.Length == 0)

{

Response.Write("Stranger, please tell me your name!");

}If the name is one of those in the names array, the message will be a bit more friendly:

// if the typed name is in the names array

else if (Array.IndexOf(names, currentUser.ToUpper().Trim()) >= 0)

{

Response.Write("Hello, master " + currentUser + "!");

}Here’s the code that outputs the text in case the name isn’t recognized:

// if the name is neither empty or recognized

else

{

Response.Write(currentUser + ", I don't know you!");

}Finally, we close the <response> element, and flush the response stream:

// output the XML document

Response.Write("</response>");

// flush the response stream

Response.Flush();

}This XML message outputted by the server (Quickstart.aspx) is read at the client by the handleServerResponse() function in Quickstart.js. More specifically, the following lines of code extract the Hello, master Yoda! message, assuming the reader has typed Yoda in the text box:

// extract the XML retrieved from the server xmlResponse = xmlHttp.responseXML; // obtain the document element (the root element) of the XML structure xmlDocumentElement = xmlResponse.documentElement; // get the text message, which is in the first child of the document element helloMessage = xmlDocumentElement.firstChild.data;

Here, xmlHttp is the XMLHttpRequest object used to call the server page Quickstart.aspx from the client. Its responseXML property extracts the retrieved XML document. XML structures are hierarchical by nature, and the root element of an XML document is called the document element. In this case, the document element is the <response> element, which contains a single child, which is the text message we’re interested in. Once the text message is retrieved, it’s displayed on the client’s page by using the DOM to access the <divMessage> element in Quickstart.html:

// update the client display using the data received

from the server

document.getElementById("divMessage").innerHTML = helloMessage;

document is a default object in JavaScript that allows you to manipulate the elements in the HTML code of your page.

The rest of the code in Quickstart.js deals with making the request to the server to obtain the XML message. The createXmlHttpRequestObject() function creates and returns an instance of the XMLHttpRequest object. This function is longer than it could be because we need to make it cross-browser compatible—we’ll discuss the details in Chapter 2. For now, it’s important to know what it does. The XMLHttpRequest instance, called xmlHttp, is used in process() to make the asynchronous server request:

// make asynchronous HTTP request using the XMLHttpRequest object

function process()

{

// proceed only if the xmlHttp object isn't busy

if (xmlHttp.readyState == 4 || xmlHttp.readyState == 0)

{

// retrieve the name typed by the user on the form

name = encodeURIComponent(document.getElementById("myName").

value);

// execute the Quickstart.aspx page from the server

xmlHttp.open("GET", "Quickstart.aspx?name=" + name, true);

// define the method to handle server responses

xmlHttp.onreadystatechange = handleServerResponse;

// make the server request

xmlHttp.send(null);

}

else

// if the connection is busy, try again after one second

setTimeout("process()", 1000);

}What you see here is, actually, the heart of AJAX—the code that makes the asynchronous call to the server.

You may wonder why it is it so important to call the server asynchronously. Asynchronous requests, by their nature, don’t freeze processing (and with it the user experience) from when the call is made until the response is received. Asynchronous processing is implemented by event-driven architectures, a good example being the way graphical user interface code is built. Without events, you’d probably need to check continuously if the user has clicked a button or resized a window. Using events, the button notifies the application automatically when it has been clicked, and you can take the necessary actions in the event handler function. With AJAX, this theory applies when making a server request—you are automatically notified when the response comes back.

If you’re curious to see how the application would work using a synchronous request, change the third parameter of xmlHttp.open() to false, and then call handleServerResponse() as shown below. If you try this, the input box where you’re supposed to write your name will freeze when the server is contacted (although the delay may not noticeable when testing this on the local machine).

// function calls the server using the XMLHttpRequest object

function process()

{

// retrieve the name typed by the user on the form

name = encodeURIComponent(document.getElementById("myName").value);

// execute the Quickstart.aspx page from the server

xmlHttp.open("GET", "Quickstart.aspx?name=" + name, false);

// synchronous server request (freezes processing until completed)

xmlHttp.send(null);

// read the response

handleServerResponse();

}The process() function is supposed to initiate a new server request using the XMLHttpRequest object. However, this is only possible if the XMLHttpRequest object isn’t busy making another request. In our case, this can happen if it takes more than one second for the server to reply, which could happen if the Internet connection is very slow. So process() starts by verifying that it is clear to initiate a new request. Chapter 2 will show more details about the various possible states of the request, but for now, it’s enough to know that a state of 0 or 4 means the connection is available to make a new request. (It’s not possible to perform more that one request through a single XMLHttpRequest object at any given time.)

// make asynchronous HTTP request using the XMLHttpRequest object

function process()

{

// proceed only if the xmlHttp object isn't busy

if (xmlHttp.readyState == 4 || xmlHttp.readyState == 0)

{So, if the connection is busy, we use setTimeout() to retry after one second (the function’s second argument specifies the number of milliseconds to wait before executing the piece of code specified by the first argument:

// if the connection is busy, try again after one second

setTimeout("process()", 1000);If the line is clear, you can safely make a new request. The lines of code that prepare the server request but don’t commit it:

// execute the Quickstart.aspx page from the server

xmlHttp.open("GET", "Quickstart.aspx?name=" + name, true);The first parameter specifies the method used to send the user name to the server, and you can choose between GET and POST (you will learn more about them in Chapter 2). The second parameter is the server page you want to access; when the first parameter is GET, you send the parameters as name/value pairs in the query string. The third parameter is true if you want the call to be made asynchronously. When making asynchronous calls, you don’t wait for a response. Instead, you define another function to be called automatically when the state of the request changes:

// define the method to handle server responses xmlHttp.onreadystatechange = handleServerResponse;

Once you’ve set this option, you can rest calm—the handleServerResponse() function will be executed by the system when anything happens to your request. After everything is set up, you initiate the request by calling the XMLHttpRequest object’s send method:

// make the server request xmlHttp.send(null); }

Let’s now look at the handleServerResponse() function:

// executed automatically when a message is received from the server

function handleServerResponse()

{

// move forward only if the transaction has completed

if (xmlHttp.readyState == 4)

{

// status of 200 indicates the transaction completed successfully

if (xmlHttp.status == 200)

{The handleServerResponse() function is called multiple times, whenever the status of the request changes. The data received from the server can be read only if xmlHttp.readyState is 4 (which happens when the response was fully received from the server), and the HTTP status code is 200, signaling that there were no problems during the HTTP request. We’ll learn more about these concepts in chapter 2. For now, suffice to say that when they are met, you can read the server response, which you can use to display an appropriate message to the user.

After the response is received and used, the process is restarted using the setTimeout() function, which will cause the process() function to be executed after one second (although that it’s not necessary, even with AJAX, to have repetitive tasks in your client-side code):

// restart sequence

setTimeout("process()", 1000);Finally, let’s reiterate what happens after the user loads the page (you can refer to Figure 1-6 for a visual representation):

1. The user loads

Quickstart.html(this corresponds to steps 1–4 in Figure 1-10).2. The user starts (or continues) typing his or her name (this corresponds to step 5 in Figure 1-10.

3. When the

process()method inQuickstart.jsis executed, it calls a server script namedQuickstart.aspxasynchronously. The text entered by the user is passed on the call as a query string parameter (viaGET). ThehandeServerResponse()function is designed to handle request state changes.4.

Quickstart.aspxexecutes on the server. It composes an XML document that encapsulates the message the server wants to transmit to the client.5. The

handleServerResponse()method on the client is executed multiple times as the state of the request changes. It’s called for the last time when the response has been successfully received. The XML is read; the message is extracted and displayed on the page.6. The user display is updated with the new message from the server, but the user can continue typing without any interruptions. After a delay of one second, the process is restarted from step 2.

This chapter was a quick introduction to the world of AJAX. In order to proceed with learning how to build AJAX applications, it’s important to understand why and where they are useful. As with any other technology, AJAX isn’t the answer to all problems, but it offers means to solve some of them.

AJAX combines client-side and server-side functionality to enhance the user experience of your site. The XMLHttpRequest object is the key element that enables the client-side JavaScript code to call a page on the server asynchronously. This chapter was intentionally short and probably has left you with many questions—that’s good! Be prepared for a whole book dedicated to answering questions and demonstrating lots of interesting functionality!