We're going to begin by assuming that your experience in Backbone is very minimal; in fact, even if you've never used Backbone before, you should still be able to follow along just fine. The application we're going to build in this chapter is a very simple blog. As blogs go, it's going to have very few features; there will be posts that viewers can read and make comments on. However, it will introduce you to every major feature in the Backbone library, get you comfortable with the vocabulary, and how these features work together in general.

By the end of this chapter, you'll know how to:

Use Backbone's model, collection, and view components

Create a Backbone router that controls everything the user sees on the screen

Program the server side with Node.js (and Express.js) to create a backend for our Backbone app

So let's get started!

Every application has to be set up, so we'll begin with that. Create a folder for your project—I'll call mine simpleBlog—and inside that, create a file named package.json. If you've used Node.js before, you know that the package.json file describes the project; lists the project home page, repository, and other links; and (most importantly for us) outlines the dependencies for the application.

Here's what the package.json file looks like:

{

"name": "simple-blog",

"description": "This is a simple blog.",

"version": "0.1.0",

"scripts": {

"start": "nodemon server.js"

},

"dependencies": {

"express": "3.x.x",

"ejs" : "~0.8.4",

"bourne" : "0.3"

},

"devDependencies": {

"nodemon": "latest"

}

}Tip

Downloading the example code

You can download the example code files for all Packt books you have purchased from your account at http://www.packtpub.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit http://www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files e-mailed directly to you.

This is a pretty bare-bones package.json file, but it has all the important bits. The name, description, and version properties should be self-explanatory. The dependencies object lists all the npm packages that this project needs to run: the key is the name of the package and the value is the version. Since we're building an ExpressJS backend, we'll need the express package. The ejs package is for our server-side templates and bourne is our database (more on this one later).

The devDependencies property is similar to the dependencies property, except that these packages are only required for someone working on the project. They aren't required to just use the project. For example, a build tool and its components, such as Grunt, would be development dependencies. We want to use a package called nodemon. This package is really handy when building a Node.js backend: we can have a command line that runs the nodemon server.js command in the background while we edit server.js in our editor. The nodemon package will restart the server whenever we save changes to the file. The only problem with this is that we can't actually run the nodemon server.js command on the command line, because we're going to install nodemon as a local package and not a global process. This is where the scripts property in our package.json file comes in: we can write simple script, almost like a command-line alias, to start nodemon for us. As you can see, we're creating a script called start, and it runs nodemon server.js. On the command line, we can run npm start; npm knows where to find the nodemon binary and can start it for us.

So, now that we have a package.json file, we can install the dependencies we've just listed. On the command line, change to the current directory to the project directory, and run the following command:

npm install

You'll see that all the necessary packages will be installed. Now we're ready to begin writing the code.

I know you're probably eager to get started with the actual Backbone code, but it makes more sense for us to start with the server code. Remember, good Backbone apps will have strong server-side components, so we can't ignore the backend completely.

We'll begin by creating a server.js file in our project directory. Here's how that begins:

var express = require('express');

var path = require('path');

var Bourne = require("bourne");If you've used Node.js, you know that the require function can be used to load Node.js components (path) or npm packages (express and bourne). Now that we have these packages in our application, we can begin using them as follows:

var app = express();

var posts = new Bourne("simpleBlogPosts.json");

var comments = new Bourne("simpleBlogComments.json");The first variable here is app. This is our basic Express application object, which we get when we call the express function. We'll be using it a lot in this file.

Next, we'll create two Bourne objects. As I said earlier, Bourne is the database we'll use in our projects in this book. This is a simple database that I wrote specifically for this book. To keep the server side as simple as possible, I wanted to use a document-oriented database system, but I wanted something serverless (for example, SQLite), so you didn't have to run both an application server and a database server. What I came up with, Bourne, is a small package that reads from and writes to a JSON file; the path to that JSON file is the parameter we pass to the constructor function. It's definitely not good for anything bigger than a small learning project, but it should be perfect for this book. In the real world, you can use one of the excellent document-oriented databases. I recommend MongoDB: it's really easy to get started with, and has a very natural API. Bourne isn't a drop-in replacement for MongoDB, but it's very similar. You can check out the simple documentation for Bourne at https://github.com/andrew8088/bourne.

So, as you can see here, we need two databases: one for our blog posts and one for comments (unlike most databases, Bourne has only one table or collection per database, hence the need for two).

The next step is to write a little configuration for our application:

app.configure(function(){

app.use(express.json());

app.use(express.static(path.join(__dirname, 'public')));

});This is a very minimal configuration for an Express app, but it's enough for our usage here. We're adding two layers of middleware to our application; they are "mini-programs" that the HTTP requests that come to our application will run through before getting to our custom functions (which we have yet to write). We add two layers here: the first is express.json(), which parses the JSON requests bodies that Backbone will send to the server; the second is express.static(), which will statically serve files from the path given as a parameter. This allows us to serve the client-side JavaScript files, CSS files, and images from the public folder.

You'll notice that both these middleware pieces are passed to app.use(), which is the method we call to choose to use these pieces.

Tip

You'll notice that we're using the path.join() method to create the path to our public assets folder, instead of just doing __dirname and 'public'. This is because Microsoft Windows requires the separating slashes to be backslashes. The path.join() method will get it right for whatever operating system the code is running on. Oh, and __dirname (two underscores at the beginning) is just a variable for the path to the directory this script is in.

The next step is to create a route method:

app.get('/*', function (req, res) {

res.render("index.ejs");

});In Express, we can create a route calling a method on the app that corresponds to the desired HTTP verb (get, post, put, and delete). Here, we're calling app.get() and we pass two parameters to it. The first is the route; it's the portion of the URL that will come after your domain name. In our case, we're using an asterisk, which is a catchall; it will match any route that begins with a forward slash (which will be all routes). This will match every GET request made to our application. If an HTTP request matches the route, then a function, which is the second parameter, will be called.

This function takes two parameters; the first is the request object from the client and the second is the response object that we'll use to send our response back. These are often abbreviated to req and res, but that's just a convention, you could call them whatever you want.

So, we're going to use the

res.render method, which will render a server-side template. Right now, we're passing a single parameter: the path to the template file. Actually, it's only part of the path, because Express assumes by default that templates are kept in a directory named views, a convention we'll be using. Express can guess the template package to use based on the file extension; that's why we don't have to select EJS as the template engine anywhere. If we had values that we want to interpolate into our template, we would pass a JavaScript object as the second parameter. We'll come back and do this a little later.

Finally, we can start up our application; I'll choose to use the port 3000:

app.listen(3000);

We'll be adding a lot more to our server.js file later, but this is what we'll start with. Actually, at this point, you can run npm start on the command line and open up http://localhost:3000 in a browser. You'll get an error because we haven't made the view template file yet, but you can see that our server is working.

All web applications will have templates of some kind. Most Backbone applications will be heavy on the frontend templates. However, we will need a single server-side template, so let's build that.

While you can choose from different template engines, many folks (and subsequently, tutorials) use Jade (http://jade-lang.com/), which is like a Node.js version of the Ruby template engine Haml (http://haml.info/). However, as you already know, we're using EJS (https://github.com/visionmedia/ejs), which is similar to Ruby's ERB. Basically, we're writing regular HTML with template variables inside <%= %> tags.

As we saw earlier, Express will be looking for an index.ejs file in the views folder, so let's create that and put the following code inside it:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title> Simple Blog </title>

</head>

<body>

<div id="main"></div>

<script src="/jquery.js"></script>

<script src="/underscore.js"></script>

<script src="/backbone.js"></script>

<script src="/app.js"></script>

</body>

</html>At this point, if you still have the server running (remember npm start on the command line), you should be able to load http://localhost:3000 without getting an error. The page will be blank, but you should be able to view the source and see the HTML code that we just wrote. That's a good sign; it means we're successfully sending stuff from the server to the client.

Since Backbone is a frontend library, it's something we'll need to be serving to the client. We've set up our Express app to statically serve the files in our public directory, and added several script tags to the index.ejs file, but we haven't created these things yet.

So, create a directory named public in your project directory. Now download the latest versions of Underscore (http://underscorejs.org), Backbone (http://backbonejs.org), and jQuery (http://jquery.com) and put them in this folder. It's very likely that newer versions of these libraries have come out since this book was written. Since updates to these projects could change the way they work, it's best to stick to the following versions:

Backbone: Version 1.1.2

Underscore: Version 1.6.0

jQuery: Version 2.0.3

I will mention here that we're including Underscore and jQuery because Backbone depends on them. Actually, it only really depends on Underscore, but including jQuery does give us a few extra features that we'll be happy to have. If you need to support older versions of Internet Explorer, you'll also want to include the json2.js library (https://github.com/douglascrockford/JSON-js), and switch to a version of jQuery 1 (jQuery 2 doesn't support older versions of IE).

Once you have these three files in the public folder, you're ready to create the app.js file. In most of our Backbone applications, this is where the major portion of the work is going to be done. Now that everything else is in place, we can begin the app-specific code.

When building a Backbone app, the first thing I like to think about is this: what data will I be working with? This is my first question because Backbone is very much a data-driven library: almost everything the user will see and work will in some way be related to a piece of data. This is especially true in the simple blog we're creating; every view will either be for viewing data (such as posts) or creating data (such as comments). The individual pieces of data that your application will work on (such as titles, dates, and text) will be grouped into what are usually called models: the posts and comments in our blog, the events in a calendar app, or the contacts in an address book. You get the idea.

To start with, our blog will have a single model: the post. So, we create the appropriate Backbone model and collection classes. The code snippet for our model is as follows:

var Post = Backbone.Model.extend({});

var Posts = Backbone.Collection.extend({

model: Post,

url: "/posts"

});There's actually a lot going on in these five lines. First, all the main Backbone components are properties of the global variable Backbone. Each of these components is a class. JavaScript does not actually have proper classes; the prototype-backed functions pass for classes in JavaScript. They also have an extend method, which allows us to create subclasses. We pass an object to this extend method, and all properties or methods inside that object will become part of the new class we're creating, along with the properties and methods that make up the class we're extending.

Tip

I want to mention early in the book that a lot of the similar code you see between Backbone apps is just convention. That's one of the reasons I love Backbone so much; there's a strong set of conventions to use, but you can totally work outside that box just as easily. Throughout the book, I'm going to do my best to show you not only the common conventions, but also how to break them.

In this code, we're creating a model class and a collection class. We actually don't need to extend the model class at all for now; just a basic Backbone model will do. However, for the collection class, we'll add two properties. First, we need to associate this collection with the appropriate model. We do this because a collection instance is basically just a glorified array for a bunch of model instances. The second property is url: this is the location of the collection on the server. What this means is that if we do a GET request to /posts, we'll get back a JSON array of the posts in our database. This also means that we will be able to send a POST request to /posts and store a new post in our database.

At this point, now that we have our data-handling classes on the frontend, I'd like to head back to the server.js file to create the routes required by our collection. So, in the file, add the following piece of code:

app.get("/posts", function (req, res) {

posts.find(function (results) {

res.json(results);

});

});First off, I'll mention that it's important that this call to app.get goes above our /* route. This is because of the fact that Express sends the requests through our routes sequentially and stops (by default, anyway) when it finds a matching one. Since /posts will match both /posts and /*, we need to make sure it hits the /posts route first.

Next, you'll recall our posts database instance, which we made earlier. Here, we're calling its find method with only a callback, which will pass the callback an array of all the records in the database. Then, we can use the response object's json method to send that array back as JSON (the Content-Type header will be application/json). That's it!

While we're here in the server.js file, we add the POST method for the same route: this is where the post data will come in from the browser and be saved to our database. The following is the code snippet for the post() method:

app.post("/posts", function (req, res) {

posts.insert(req.body, function (result) {

res.json(result);

});

});The req object has a body property, which is the JSON data that represents our post data. We can insert it directly into the posts database. When Backbone saves a model to the server in this way, it expects the response to be the model it sent with an ID added to it. Our database will add the ID for us and pass the updated model to the callback, so we only have to send it as a response to the browser, just as we did when sending all the posts in the previous method using res.json.

Of course, this isn't very useful without a form to add posts to the database, right? We'll build a form to create new posts soon, but for now we can manually add a post to the simpleBlogPosts.json file; this file may not exist yet because we haven't written any data, so you'll have to create it. Just make sure the file you create has the right name, that is, the same name as the parameter we passed to the Bourne constructor in our server.js file. I'm going to put the following code in that file:

[

{

"id": 1,

"pubDate": "2013-10-20T19:42:46.755Z",

"title": "Lorem Ipsum",

"content": "<p>Dolor sit amet . . .</p>"

}

]Of course, you can make the content field longer; you get the idea. This is the JSON field that will be sent to our Posts collection instance and become a set of the Post model instance (in this case, a set of only one).

We've actually written enough code at this point to test things out. Head to http://localhost:3000 in your browser and pop open a JavaScript console; I prefer Chrome and the Developer tools but use whatever you want. Now try the following lines:

var posts = new Posts(); posts.length // => 0

We can create a Posts collection instance; as you can see, it's empty by default. We can load the data from the server by running the following line:

posts.fetch();

A collection instance's fetch method will send a GET request to the server (in fact, if your in-browser tools allow you to see a network request, you'll see a GET request to /posts). It will merge the models that it receives from the server with the ones already in the collection. Give a second to get a response and then run the following lines:

posts.length // => 1 var post = posts.get(1); post.get("title"); // Lorem Ipsum

Every collection instance has a get method; we pass it an ID and it will return the model instance with that ID (note that this is the id field from the database, and not the index number in the collection). Then, each model instance has a get method that we can use to get properties.

In simple applications like the one we're creating in this chapter, most of the Backbone code that we write will be in views. I think it's fair to say that views can be the most challenging part of a Backbone app, because there are so many ways that almost everything can be done.

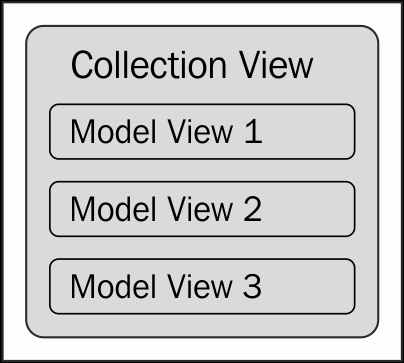

It's important to understand that a Backbone.View instance and a screen full of web apps aren't the same thing. One view in the browser may actually be many Backbone views. The first view that we want to create is a list of all the posts; these will be links to individual post pages. We could do this in two ways: as one big view or as multiple smaller views put together. In this instance, we're going to be using multiple views. Here's how we'll break it down: each list item will be generated by its own view instance. Then, the wrapper around the list items will be another view. You can picture it as looking something like this:

Let's start with the child views. We'll call this PostListView class. Naming views can be a little tricky. Often, we'll have a view for the collection and a view for the model, and we'll just append View to the end of their names, for example, PostView and PostsView. However, a model or collection will have multiple views. The one we're about to write is to list our models. That's why we're calling it PostListView:

var PostListView = Backbone.View.extend({

tagName: "li",

template: _.template("<a href='/posts/{{id}}'>{{title}}</a>"),

render: function () {

this.el.innerHTML = this.template(this.model.toJSON());

return this;

}

});Just like Backbone.Model and Backbone.Collection, we create a view class by extending Backbone.View. We have three properties in the extending object that make up our PostListView. The first one to look at is the template property; this property holds the template that our view will render. There are plenty of ways to create a template; in this case, we're using the Underscore's template function; we pass a string to _.template, and it returns a function which we can use to generate the correct HTML. Take a look at this template string: it's regular HTML with variables placed within double curly braces.

Next, let's look at the render method. By convention, this is the method that we call to actually render the view. Every view instance has a property named el. This is the base element for the view instance: all other elements for this view go inside it. By default, this is a div element, but we've set the tagName property to li, which means we'll get a list item instead. By the way, there's also a $el property, which is a jQuery object wrapping the el property; this only works if we have jQuery included in our application.

So, inside our render function, we need to fill in this element. In this case, we'll do that by assigning the innerHTML property. To get the HTML output, we use the template we just wrote. That's a function, so we call it, and pass this.model.toJSON(). The this.model portion comes from when we instantiate this view: we'll pass it a model. Every model has a toJSON method, which returns a raw object with just the attributes of the model. Since our model will have the id and title attributes, passing this to our template function will return a string with those values interpolated into the template string we wrote.

We end our render function by returning the view instance. Again, this is just convention. Because of this, we can use the convention where we get the element for this view via view.render().el ; this will render the view and then get the el property. Of course, there's no reason you couldn't return this.el directly from render.

There's one more thing to address here, but it's about Underscore and not Backbone. If you've used the Underscore's template function before, you know that curly braces aren't its normal delimiters. I've switched from the default <%= %> delimiters, because those are the delimiters for our server-side template engine. To change Underscore's delimiters, just add the following code snippet to the top of our app.js file:

_.templateSettings = {

interpolate: /\{\{(.+?)\}\}/g

};Of course, you realize that we could make the delimiters whatever we want, as long as a regular expression can match it. I like the curly braces.

Now that we have the view for our list items, we need the parent view that wraps those list items:

var PostsListView = Backbone.View.extend({

template: _.template("<h1>My Blog</h1><ul></ul>"),

render: function () {

this.el.innerHTML = this.template();

var ul = this.$el.find("ul");

this.collection.forEach(function (post) {

ul.append(new PostListView({

model: post

}).render().el);

});

return this;

}

});As views go, this is pretty simple, but we can learn a few new things from it. First, you'll notice that our template doesn't actually use any variables, so there's no reason for us to actually use a template. We could directly assign that HTML string as this.el.innerHTML; however, I like to do the little template dance anyway because I might change the template string to include some variables in the future.

Notice the second line of the render function: we're finding an ul element; the same ul element that we just made as a child element of our root element, this.el. However, instead of using this.el, we're using this.$el.

Next, we're looping over each item in the collection that we'll associate with this view (when we instantiate it). For each post in the collection, we will create a new PostListView class. We pass it an options object, which assigns the view's model as the current post. Then, we render the view and return the view's element. This is then appended to our ul object.

We'll end by returning the view object.

We're almost ready to actually display some content in the browser. Our first stop is back in the server.js file. We need to send the array of posts from the database to our index.ejs template. We do this by using the following code snippet:

app.get('/*', function (req, res) {

posts.find(function (err, results) {

res.render("index.ejs", { posts: JSON.stringify(results) });

});

});Just as we do in the /posts route, we call posts.find. Once we get the results back, we render the view as before. But this time, we pass an object of values that we want to be able to use inside the template. In this case, that's only the posts. We have to run the results through JSON.stringify, because we can't serve an actual JavaScript object to the browser; we need a string representation (the JSON form) of the object.

Now, in the index.ejs file of the views folder, we can use these posts. Create a new script tag under the other ones we created before. This time, it will be an inline script:

<script>

var posts = new Posts(<%- posts %>);

$("#main").append(new PostsListView({

collection: posts

}).render().el);

</script>The first line creates our posts collection; notice our use of the template tags. This is how to interpolate our posts array into the template. There's no typo there by the way; you might have expected an opening tag of <%=, but that opening tag will escape any possible characters in the string, which wrecks the quotes in our JSON code. So, we use <%-, which doesn't escape characters.

The next line should be pretty straightforward. We're using jQuery to find our main element and appending the element of a new PostsListView instance. In the options object, we'll set the collection for this view. We then render it and find the element to append.

Now, make sure your server is running, and go to http://localhost:3000 in the browser. You should see the following screenshot:

You're using the three main Backbone components—collection, models, and views—to create a mini-application! That's great, but we've only just got started.

Go ahead and click on the link that we've just rendered. You'll find that the URL changes and the page refreshes, but the content is still the same. This is because of a choice we've made in how our application works, that is, we made a catchall route that matches every GET request to our server. This means that /, /posts/1, and /not/a/meaningful/link show us the same content. This is what's often called a single-page web application, that is, as much as possible is done on the client side, with JavaScript doing the heavy lifting, and not a different language on the server. With this kind of application, the whole thing could work off a single URL that never changes. However, this makes it hard to bookmark parts of the application. So, we want to make sure our application uses good URLs. To do this, we need to create a Backbone router as follows:

var PostRouter = Backbone.Router.extend({

initialize: function (options) {

this.posts = options.posts;

this.main = options.main;

},

routes: {

'': 'index',

'posts/:id': 'singlePost'

},

index: function () {

var pv = new PostsListView({ collection: this.posts }

this.main.html(pv.render().el);

},

singlePost: function (id) {

console.log("view post " + id);

}

});Here's the first version of our PostRouter. You should see a familiar pattern as we begin: we extend the component Backbone.Router. The next important piece is the initialize method. We never add one of these to our model, collection, or views, but they can all take an initialize method. This is the constructor function for our router. In good old Backbone convention, we expect to get a single options parameter. We'll expect this object to have two properties: posts and main. These should be the posts collection and the div#main element, respectively. We'll assign these as properties on our router instance.

Note

Technically, the initialize function isn't the constructor function. It's a function that is called by the constructor function. To completely replace the default behavior, write a method called constructor, not initialize.

The next important part is the routes object. In this object, the keys are routes and the values are the router methods to call when those routes are used. So, the same page will be loaded from the server, but then the client-side router will look at exactly what URL was requested and show the right content.

The first route is an empty string; this is the / route (but it's best practice not to include the slash in the front, so that the router will work with both hash URLs and the pushState API). When we load that route, we'll run the router's index function.

So what does this function do? It should look familiar; it's like what we put in our index.ejs file as a quick test. It creates our PostsListView instance and puts it on the page. Notice that we're using the this.posts and this.main properties that we just created.

The other route we're creating here is /posts/:id, which runs the singlePost function. The colon-label portion of that route will catch the content after that slash and pass it to the route method as a parameter. Right now, all we're doing in the singlePost method is logging a message to the console, but there's more to come.

Now that we've written a router, we need to start using it. You know that inline script in the index.ejs file? Replace its content with the following code:

var postRouter = new PostRouter({

posts: new Posts(<%- posts %>),

main: $("#main")

});

Backbone.history.start({pushState: true});Once again, we're creating the posts collection and the references to the main <div> element. This time, however, they're properties of the router. We actually don't have to do anything with the router instance, just create it. However, we do have to start the history tracking: that's what the last line does. Remember, we're using a single-page app, so our URLs are not actual routes on the server. This used to be done with a hash in the URL, but the better and more modern way to do this is with the pushState API, which is a browser API that let's you change the URL in the browser's address bar without actually changing the contents of the page. So, that's what we do with the options object, where we set pushState to true.

If you browse your way over to http://localhost:3000/, you'll see our post listing. Now, click on the post link, and well, the page still reloads. However, on the new link, you see no page content but a line logged to the console. So, the router is working but it isn't stopping the reload. When the page reloads, the router sees the new route and runs the right method.

So the question now is, how do we keep the page from refreshing, but still change the URL? To do this, we have to prevent the default behavior of the link that we clicked on. To do this, we need to add the following pieces to our PostListView (in the app.js file):

events: {

'click a': 'handleClick'

},

handleClick: function (e) {

e.preventDefault();

postRouter.navigate($(e.currentTarget).attr("href"),

{trigger: true});

}The events property is important here, as it handles any DOM events that happen within the base element of our view. The keys in this object should follow the pattern eventName selector. Of course, eventName can be any DOM event. The selector should be a string that jQuery can match. Part of the beauty of this selector is that it only matches elements within this view, so you often don't have to make it very specific. In our case, just 'a' is good enough.

The value of each events property is the name of the method to call when this event occurs. The next step is to write this method as another property of this same view; it gets the jQuery event object as a parameter. Inside the handleClick method, we're calling e.preventDefault to keep the default behavior from happening. Since this is an anchor element, the default behavior is switching to the linked-to page. Instead, we perform that navigation inside our Backbone application: that's the next line.

What we're doing here isn't a completely good idea, but it will work for now. We're referencing the postRouter variable, which isn't created in this file; in fact, it's created after this file is loaded on the client. We can get away with this because this function won't be called until after the postRouter variable is created. However, in a more serious application, we would probably want better code decoupling. However, for our skill level, this is okay.

We're calling the router's navigate method. The first parameter is the route to navigate to: we get this from the anchor element. We also pass an options object, which sets trigger to true. If we don't trigger the navigation, the URL will change in the browser's location bar, but nothing else will change. Since we are triggering the navigation, the appropriate router method will be called, if one exists. One does in our case, singlePost, so you should see our message printed to the JavaScript console in the browser.

Now that we have the right URL for a post page, let's make a view for individual posts:

var PostView = Backbone.View.extend({

template: _.template($("#postView").html()),

events: {

'click a': 'handleClick'

},

render: function () {

var model = this.model.toJSON();

model.pubDate = new Date(Date.parse(model.pubDate)).toDateString();

this.el.innerHTML = this.template(model);

return this;

},

handleClick: function (e) {

e.preventDefault();

postRouter.navigate($(e.currentTarget).attr("href"),

{trigger: true});

return false;

}

});This view should mark an important milestone in your Backbone education: you understand most of the conventions that you're looking at in this code. You should recognize all the properties of the view, as well as most of the method content. I want to point out here there's much more convention going on than you may realize. For example, the template property is only ever referred to inside the render method, so you could call it something different, or put it inside the render method, as shown in the following line of code:

var template = _.template($("#postView").html());Even the render method is only used by us when rendering the view. It's convention to call it render, but really, nothing will break if you don't. Backbone never calls it internally.

Tip

You might wonder why we follow these Backbone conventions if we don't have to. I think it's partly because they are very sensible defaults, and because it makes reading other people's Backbone code much easier. However, another good reason to do it is because there are many third-party Backbone components that depend on these conventions. When using them, conventions become expectations that are required for things to work.

However, there are a few things in this view that will be new to you. First, instead of putting the template text in a string that gets passed directly to _.template, we're putting it in the index.ejs file and using jQuery to pull it in. This is something you'll see often; it's handy to do because most applications will have larger templates, and it's hard to manage a lot of HTML in JavaScript strings. So, put the following code in your index.ejs file related to your "actual" script tags:

<script type="text/template" id="postView">

<a href='/'>All Posts</a>

<h1>{{title}}</h1>

<p>{{pubDate}}</p>

{{content}}

</script>It's important to give your script tag a type attribute, so the browser doesn't try to execute it as JavaScript. What that type is doesn't really matter; I use text/template. We also give it an id attribute, so we can reference it from the JavaScript code. Then, in our JavaScript code, we use jQuery to get the element, and then get its content using the html method.

The other different piece of this view is that we're not passing this.model.toJSON() directly to the render method. Instead, we're saving it to the model variable, so that we can format the pubDate property. When stored as JSON, dates aren't very pretty. We use a few built-in Date methods to fix this up and reassign it to the model. Then, we pass the updated model object to the render method.

If you're wondering why we're using events and handleClick to override the anchor action again, notice the All Posts link in our template; this will be displayed above our post content. However, I hope you notice the flaw in this pattern: this will sabotage all links that might be in the content of our post, which might lead outside our blog. This is another reason why, as I said earlier, this pattern of view-changing isn't that great; we'll look at improvements on this in future chapters.

Now that we've created this view, we can update the singlePost method in our router:

singlePost: function (id) {

var post = this.posts.get(id);

var pv = new PostView({ model: post });

this.main.html(pv.render().el);

}Instead of just logging the ID to the console, we find the post with that ID in our this.posts collection. Then, we create a PostView instance, giving it that post as a model. Finally, we replace the content of the this.main element with the rendered content of the post view.

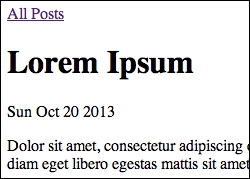

If you do a simple click-through test now, you should be able to go to our home page, click on the post's title, and see this:

You should be congratulated! You've just built a complete Backbone application (albeit an application with an extremely low level of functionality but an application nonetheless).

Now that we can show posts, let's create a form to make new posts. It's important to realize that we're just going to create a form. There's no user account and no authentication, just a form that anyone could use to make new posts. We'll start with the template, which we'll put in the index.ejs file:

<script type="text/template" id="postFormView"> <a href="/">All Posts</a><br /> <input type="text" id="postTitle" placeholder="post title" /> <br /> <textarea id="postText"></textarea> <br /> <button id="submitPost"> Post </button> </script>

It's a very basic form, but it will do. So now, we need to create our view; use the following code:

var PostFormView = Backbone.View.extend({

tagName: 'form',

template: _.template($("#postFormView").html()),

initialize: function (options) {

this.posts = options.posts;

},

events: {

'click button': 'createPost'

},

render: function () {

this.el.innerHTML = this.template();

return this;

},

createPost: function (e) {

var postAttrs = {

content: $("#postText").val(),

title: $("#postTitle").val(),

pubDate: new Date()

};

this.posts.create(postAttrs);

postRouter.navigate("/", { trigger: true });

return false;

}

});It's pretty big, but you should be able to understand most of it. We start by making the view a <form> element through the tagName property. We fetch the template we just created in the template property. In the initialize method, we take a Posts collection as an option and assign it as a property, much like we did in the router. In the events property, we listen for a click event on the button. When that happens, we call the createPost method. Rendering this view is pretty simple. Actually, the real complexity here is in the createPost method, but even that is pretty simple. We create a postAttrs object that has all the properties of our post: the content and the text from the form and a date that we add.

After creating this postAttrs object, we pass it to the Posts collection's create method. This is a convenience method, really, that creates the Post model instance, saves it to the server, and adds it to the collection. If we wanted to do this "manually", we'd do something similar to the following lines of code:

var post = new Post(commentAttrs); this.posts.add(post); post.save();

Every Backbone model constructor takes an object, which is a hash of attributes. We can add that model to the collection using the add method. Then, every model instance has a save method, which sends the model to the server.

Note

In this case, it's important to add the model to the collection before saving it, because our model class doesn't know the server route to POST to on its own. If we wanted to be able to save model instances that aren't in a collection, we'd have to give the model class a urlRoot property:

urlRoot: "/posts",

Finally, we navigate back to the home page.

The next step is to add a new route to the router. In the routes property of the router class, add the following line:

'posts/new': 'newPost'

Then, we add the newPost method, which is very simple:

newPost: function () {

var pfv = new PostFormView({ posts: this.posts });

this.main.html(pfv.render().el);

},That's all! Like I said, this isn't how you'd really do blog posting in a proper blog, but it shows us how to send model data back to the server.

Let's take things one step further, shall we? Let's add some (very primitive) commenting functionality.

Once again, we should start by thinking about the data. It's obvious, in this case: our basic data object, if you will, is the comment. However, we also need to think about how our data needs to interact with other data in the application, that is, every post that we have needs to be able to have multiple comments connected to it. Backbone doesn't have any conventions for inter-model-and-collection relationships, so we'll come up with something on our own.

We start with model and collection, as shown in the following code:

var Comment = Backbone.Model.extend({});

var Comments = Backbone.Collection.extend({

initialize: function (models, options) {

this.post = options.post;

},

url: function () {

return this.post.url() + "/comments";

}

});You remember the initialize function, right? This will run when we instantiate the collection. Conventionally, it takes two parameters: an array of models and an options object. We'll expect a collection of comments to be related to a single post, and we get that post as an option.

In our Posts collection, url was a string property; however, it can also be a function that returns a string if we need a more dynamic URL. This is exactly what we need for our Comments collection because the URL is dependent upon the post. As you can see, the server location of a collection of comments is the URL for the post, plus /comments. So, for a post with ID 1, it's /posts/1/comments. For a post with ID 42, it's /posts/42/comments, and so on.

Note

The url method on a model instance checks to see whether our model class has the property urlRoot; if so, it will use that. Otherwise, it uses its collection's url property. In either case, it will append its id property to the url property to get its own unique URL.

The next step is to loosely connect the Comments collection to the Post model. We need to add an initialize method to our Post model as shown here:

var Post = Backbone.Model.extend({

initialize: function () {

this.comments = new Comments([], { post: this });

}

});I say "loosely" because there's no actual relation here between a post and its own comments (apart from setting post: this in the options object, which helps set the current URL); all this does is create a new Comments collection whenever a post is created. It's important to realize that this comments property is not like the other properties of a model. To be specific, it's a regular JavaScript property of the object, but not an attribute of the post model itself. We can't get it with the model's get method.

The next step is to prepare the server to send and receive comments. Sending comments to the client is actually pretty; see here:

app.get("/posts/:id/comments", function (req, res) {

comments.find(

{ postId: parseInt(req.params.id, 10) },

function (err, results) {

res.json(results);

}

);

});Just like in the Backbone router routes, we can use colon-target-style tokens in our Express routes to take a variable. However, instead of showing up as function parameters, we can get them as a subproperty of the request object req.param.

We're using the comments database object we created previously. The database has a find method, which takes a query object as the first parameter. In this case, we just want to find all comment records that have a postId property that matches the id parameter from the URL. Since the id parameter is a string, we'll need to use parseInt to convert it to a number. When we get the records, we'll send them back as JSON, just like we did with the posts.

What about saving comments? These will be POSTed back to the server as the request body, and they're POSTed to the same URL, you can see in the following code:

app.post("/posts/:id/comments", function (req, res) {

comments.insert(req.body, function (err, result) {

res.json(result);

});

});Since we're parsing the request body as JSON (see the middleware we added), we can insert it directly into our database. In our callback, we're taking a result parameter and sending it back to the client as JSON. This is important, because the id property on Backbone models should be set on the server. Our database does this automatically, so the result we send back is the same object we received with a new id property. This is the response Backbone expects.

Now, we're ready to create the comment views. This could be done in many ways, but we're going to do it with three view classes. The first is to display individual comments. The second is the form to create new comments. The third wraps these two views and adds some important functionality.

The first is the simplest, so let's start with it:

var CommentView = Backbone.View.extend({

template: _.template($("#commentView").html()),

render: function () {

var model = this.model.toJSON();

model.date = new Date(Date.parse(model.date)).toDateString();

this.el.innerHTML = this.template(model);

return this;

}

});We're formatting the date, as we did previously, for posts. Also, we're once again putting the template content in a script tag. Here's the script tag that goes in the index.ejs file:

<script type="text/template" id="commentView">

<hr />

<p><strong>{{name}}</strong> said on {{date}}: </p>

<p>{{text}}</p>

</script>Pretty straightforward, isn't it?

Next up is the CommentFormView class. This is the form that viewers will use to add a comment to post. We'll start with the template this time by using the following code:

<script type="text/template" id="commentFormView"> <input type="text" id="cmtName" placeholder="name" /><br /> <textarea id="cmtText"></textarea><br /> <button id="submitComment"> Submit </button> </script>

Nothing too special: a textbox for the name, a text area for the text, and a submit button. A very basic form, you'll agree. Now we have the class itself:

var CommentFormView = Backbone.View.extend({

tagName: "form",

initialize: function (options) {

this.post = options.post;

},

template: _.template($("#commentFormView").html()),

events: {

'click button': 'submitComment'

},

render: function () {

this.el.innerHTML = this.template();

return this;

},

submitComment: function (e) {

var name = this.$("#cmtName").val();

var text = this.$("#cmtText").val();

var commentAttrs = {

postId: this.post.get("id"),

name: name,

text: text,

date: new Date()

};

this.post.comments.create(commentAttrs);

this.el.reset();

}

});This form view is long, but pretty similar to the other form, the one for creating posts. The tagName property sets the view's base element to a form. Since the comments this form makes need to be related to a post, we set the post as a property via the options object in the initialize method.

Note

Instead of creating a post property on this view, we could use the model property. As you may have noticed, this is a specially-named property that gets assigned automatically when it's part of the options object (so we wouldn't need an initialize method). However, that property is usually the model that is displayed in this view. Since that's not what we're using here, I prefer to make a custom property, so someone reading this code wouldn't misunderstand the purpose of the post model in this view.

Of course, we'll need to capture the click event on the Submit button. When that happens, the submitComment method will be run. The first portion of this method is simple; we're getting the values from the textbox and text area. Then, we're putting together a commentAttrs object with four properties: the ID of the post this comment belongs to, the name of the commenter, the text, and the date and time of the comment's creation (right now).

After creating this commentAttrs object, we pass it to the post's comment collection's create method, just as we did in the PostFormView. The final line in the submitComment method is a built-in DOM method that resets the form; it clears all fields.

The last view is CommentsView, which pulls these two view classes together, as shown here:

var CommentsView = Backbone.View.extend({

initialize: function (options) {

this.post = options.post;

this.post.comments.on('add', this.addComment, this);

},

addComment: function (comment) {

this.$el.append(new CommentView({

model: comment

}).render().el);

},

render: function () {

this.$el.append("<h2> Comments </h2>");

this.$el.append(new CommentFormView({

post: this.post

}).render().el);

this.post.comments.fetch();

return this;

}

});Just like CommentFormView, this view will be given a Post instance when it's created. In the render method, we first append a heading to the view element, and then we render and append our comment form. All this should look relatively familiar, but the rest is new. The second-last line in render calls the fetch method of the post's comments collection. This makes a GET request to the server and fills the collection with the comments that are returned from the server.

Now, look back at the initialize method; the last line is the first we've seen of Backbone's event capabilities. As we perform different tasks and call different methods of Backbone objects, different events are triggered, and we can listen for those events and react when they occur. In this case, we're listening for the comment collection's add event. This event occurs whenever we add a new model to this collection. If you think about the code we've written, you'll see that there are two places where we add models to this collection:

When calling

comments.createin thesubmitCommentmethod inCommentFormViewWhen calling

comments.fetchin therendermethod in this view

So, whenever a model is added to our collection, we want to call the this.addComment method. Notice that we're passing a third parameter to the on method: this. This is the context for the function we want to call. By default, there will be no value for this inside functions called by the on method, so we want to tell it to use this view instance as context.

The addComment method takes the freshly-added comment as a parameter (the collections object and an options object are also passed to functions that are responding to an add event, but we don't need them here). We can then create a CommentView instance for this model and append its element to our view element.

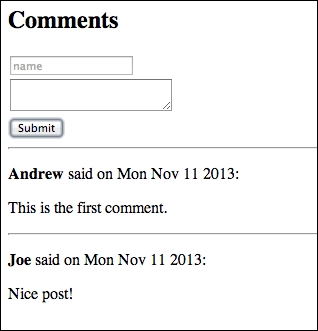

Well, it's all there now. You can go ahead and give it a try, that is, load a post page and add a few comments. Each time, you should see the comment appear below the form. Then, if you refresh the page, the comments you made will again appear under the post. You might notice a little delay in the loading of the comments. This is because we aren't loading them with the initial page load. Instead, they are loaded during the rendering of CommentsView. Granted, this is milliseconds after the page load, but you might see a quick flash. You will see the following on your screen:

This brings us to the end of the first chapter. If you hadn't dug into Backbone much before this, I hope that you're starting to feel comfortable with the basics of the library.

In this chapter, we looked briefly at all the main components of Backbone. We saw how models and collections are the homes for our data records, and how they drive the web application. We made a handful of views, some to display individual model instances, some to display a collection, and some to display other page components or wrap other views. We created a router and used it to direct almost all the traffic on our web application. We even got a little taste of Backbone's robust events API.

Besides the nitty-gritty of the Backbone API, I hope you picked up some of the bigger ideas. One of these is the options object, as almost every Backbone component constructor function takes an options object as the final parameter, and many functions that interact with the server do as well. There are some magic property names—such as model or collection—that Backbone handles automatically, but you can also pass your own options and work with them inside the classes.

The other big takeaway from this chapter is the balance between convention and choice when coding. Compared to the other similar libraries, Backbone is incredibly light and flexible and enforces very few coding patterns. The good part is that the few conventions that Backbone does strongly support are actually really great ideas that it makes sense to follow. Of course, it's just one programmer's opinion, but I've found that Backbone engenders an almost perfect balance of convention to follow and freedom to code however you want. We'll learn more about this balance when we build a photo-sharing application in the next chapter.