Tuples

A tuple object is similar to a list, but it cannot be changed. Tuples are immutable sequences, which means their values cannot be changed after initialization. You can use a tuple to represent fixed collections of items:

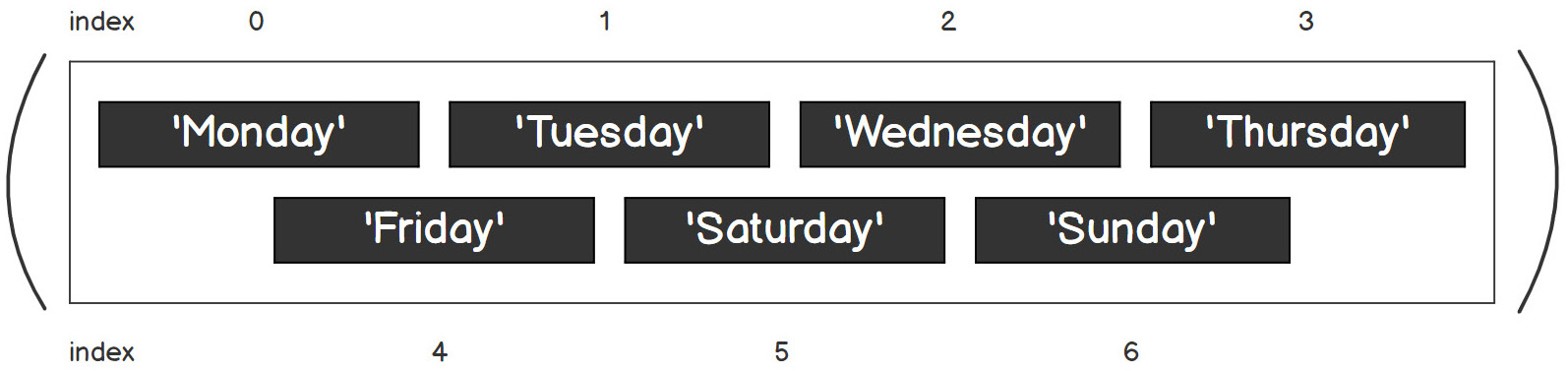

Figure 2.17 – A representation of a Python tuple with a positive index

For instance, you can define the weekdays using a list, as follows:

weekdays_list = ['Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday',

'Thursday','Friday','Saturday', 'Sunday']

However, this does not guarantee that the values will remain unchanged throughout their life because a list is mutable. What you can do is define it using a tuple, as shown in the following code:

weekdays_tuple = ('Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday',

'Thursday','Friday','Saturday', 'Sunday')

As tuples are immutable, you can be certain that the values are consistent throughout the entire program and will not be modified accidentally or unintentionally. In the next exercise, you will explore the different properties tuples provide a Python developer.

Exercise 31 – exploring tuple properties in a dance genre list

In this exercise, you will learn about the different properties of a tuple:

- Open a Jupyter notebook.

- Type the following code in a new cell to initialize a new tuple,

t:t = ('ballet', 'modern', 'hip-hop')print(len(t))

The output is as follows:

3

Note

Remember, a tuple is immutable; therefore, you can’t use the append method to add a new item to an existing tuple. You can’t change the value of any existing tuple’s elements since both of the following statements will raise an error.

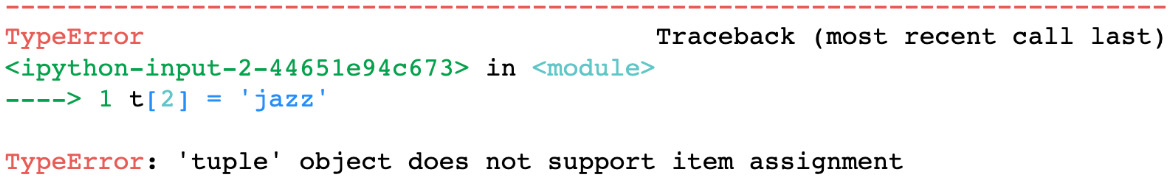

- Now, as mentioned in the note, enter the following lines of code and observe the error:

t[2] = 'jazz'

The output is as follows:

Figure 2.18 – Errors occur when we try to modify the values of a tuple object

The only way to get around this is to create a new tuple by concatenating the existing tuple with other new items.

- Now, use the following code to add two items,

jazzandtap, to our tuple,t. This will give us a new tuple. Note that the existingttuple remains unchanged:print(t + ('jazz', 'tap'))print(t)

('ballet', 'modern', 'hip-hop', 'jazz', 'tap')

('ballet', 'modern', 'hip-hop')

- Enter the following statements in a new cell and observe the output:

t_mixed = 'jazz', True, 3

print(t_mixed)

t_dance = ('jazz',3), ('ballroom',2),('contemporary',5)print(t_dance)

Tuples also support mixed types and nesting, just like lists and dictionaries. You can also declare a tuple without using parentheses, as shown in the code you entered in this step.

('jazz', True, 3)

(('jazz', 3), ('ballroom', 2), ('contemporary', 5))

Zipping and unzipping dictionaries and lists using zip()

Sometimes, you obtain information from multiple lists. For instance, you might have a list to store the names of products and another list just to store the quantity of those products. You can aggregate these lists using the zip() method.

The zip() method maps a similar index of multiple containers so that they can be used as a single object. You will try this out in the following exercise.

Exercise 32 – using the zip() method to manipulate dictionaries

In this exercise, you will work on the concept of dictionaries by combining different types of data structures. You will use the zip() method to manipulate the dictionary with our shopping list. The following steps will help you understand the zip() method:

- Open a new Jupyter Notebook.

- Now, create a new cell and type in the following code:

items = ['apple', 'orange', 'banana']

quantity = [5,3,2]

Here, you have created a list of items and a list of quantity. Also, you have assigned values to these lists.

- Now, use the

zip()function to combine the two lists into a list of tuples:orders = zip(items,quantity)

print(orders)

This gives us a zip() object with the following output:

<zip object at 0x0000000005BF1088>

- Enter the following code to turn that

zip()object into alist:orders = zip(items,quantity)

print(list(orders))

The output is as follows:

[('apple', 5), ('orange', 3), ('banana', 2)]

- You can also turn a

zip()object into atuple:orders = zip(items,quantity)

print(tuple(orders))

Let’s see the output:

(('apple', 5), ('orange', 3), ('banana', 2))

- You can also turn a

zip()object into a dictionary:orders = zip(items,quantity)

print(dict(orders))

Let’s see the output:

{'apple': 5, 'orange': 3, 'banana': 2}

Did you realize that you have to call orders = zip(items,quantity) every time? In this exercise, you will have noticed that a zip() object is an iterator, so once it has been converted into a list, tuple, or dictionary, it is considered a full iteration and it will not be able to generate any more values.