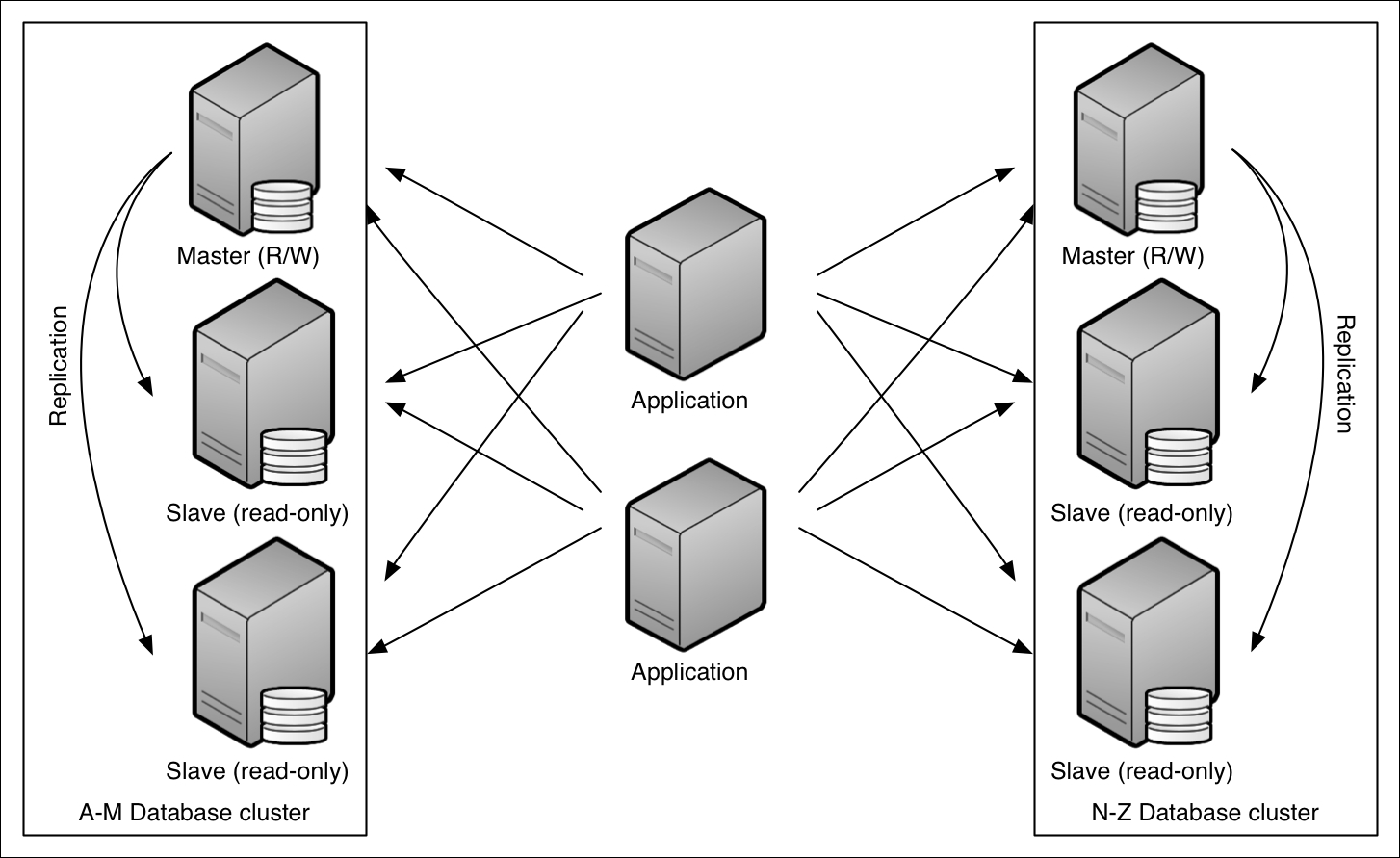

Cassandra's peer-to-peer approach

Unlike either monolithic or master-slave designs, Cassandra makes use of an entirely peer-to-peer architecture. All nodes in a Cassandra cluster can accept reads and writes, no matter where the data being written or requested actually belongs in the cluster. Internode communication takes place by means of a gossip protocol, which allows all nodes to quickly receive updates without the need for a master coordinator.

This is a powerful design, as it implies that the system itself is both inherently available and massively scalable. Consider the following diagram:

Note that in contrast to the monolithic and master-slave architectures, there are no special nodes. In fact, all nodes are essentially identical and as a result Cassandra has no single point of failure, and therefore no need for complex sharding or leader election. But how does Cassandra avoid sharding?

Cassandra is able to achieve both availability and scalability using a data structure that allows any node in the system to easily determine the location of a particular key in the cluster. This is accomplished by using a distributed hash table (DHT) design based on the Amazon Dynamo architecture.

As we saw in the previous diagram, Cassandra's topology is arranged in a ring, where each node owns a particular range of data. Keys are assigned to a specific node using a process called consistent hashing, which allows nodes to be added or removed without having to rehash every key based on the new range.

The node that owns a given key is determined by the chosen partitioner. Cassandra ships with several partitioner implementations, or developers can define their own by implementing a Java interface.

These topics will be covered in greater detail in the next chapter.

Replication across the cluster

One of the most important aspects of a distributed data store is the manner in which it handles replication of data across the cluster. If each partition were only stored on a single node, the system would effectively possess many single points of failure, and a failure of any node could result in catastrophic data loss. Such systems must therefore be able to replicate data across multiple nodes, making the occurrence of such loss less likely.

Cassandra has a sophisticated replication system, offering rack and data center awareness. This means it can be configured to place replicas in such a manner so as to maintain availability even during otherwise catastrophic events such as switch failures, network partitions, or data center outages. Cassandra also includes a mechanism that maintains the replication factor during node failures.

Replication across data centers

Perhaps the most unique feature Cassandra provides to achieve high availability is its multiple data center replication system. This system can be easily configured to replicate data across either physical or virtual data centers. This facilitates geographically dispersed data center placement without complex schemes to keep data in sync. It also allows you to create separate data centers for online transactions and heavy analysis workloads, while allowing data written in one data center to be immediately reflected in others.

Chapter 3

, Replication

and

Chapter 4

, Data Centers, will provide a complete discussion of Cassandra's extensive replication features.

The consistency continuum

Closely related to replication is the idea of consistency, the C in ACID that attempts to keep replicas in sync. Cassandra is often referred to as an eventually consistent system, a term that can cause fear and trembling for those who have spent many years relying on the strong consistency characteristics of their favorite relational databases. However, as previously discussed, consistency should be thought of as a continuum, not as an absolute.

With this in mind, Cassandra can be more accurately described as having tunable consistency, where the precise degree of consistency guarantee can be specified on a per-statement level. This gives the application architect ultimate control over the trade-offs between consistency, availability, and performance at the call level, rather than forcing a one-size-fits-all strategy onto every use case.

Any discussion of consistency would be incomplete without at least reviewing the CAP theorem. The CAP acronym refers to three desirable properties in a replicated system:

Consistency: This means that the data should appear identical across all nodes in the cluster

Availability: This means that the system should always be available to receive requests

Partition tolerance: This means that the system should continue to function in the event of a partial failure

In 2000, computer scientist Eric Brewer from the University of California, Berkeley, posited that a replicated service can choose only two of the three properties for any given operation.

The CAP theorem has been widely misappropriated to suggest that entire systems must choose only two of the properties, which has led many to characterize databases as either AP or CP. In fact, most systems do not fit cleanly into either category, and Cassandra is no different.

Brewer himself addressed this misguided interpretation in his 2012 article, CAP Twelve Years Later: How the "Rules" Have Changed:

".. all three properties are more continuous than binary. Availability is obviously continuous from 0 to 100 percent, but there are also many levels of consistency, and even partitions have nuances, including disagreement within the system about whether a partition exists"

In that same article, Brewer also pointed out that the definition of consistency in ACID terms differs from the CAP definition. In ACID, consistency refers to the guarantee that all database rules will be followed (unique constraints, foreign key constraints, and the like). The consistency in CAP, on the other hand, as clarified by Brewer, refers only to single-copy consistency, a strict subset of ACID consistency.

Note

When considering the various trade-offs of Cassandra's consistency level options, it's important to keep in mind that the CAP properties exist on a continuum rather than as binary choices.

The bottom line is that it's important to bear this continuum in mind when designing a system based on Cassandra. Refer to

Chapter 3

, Replication, for additional details on properly tuning Cassandra's consistency level under a variety of circumstances.