By running the first unique_ptr program, that is, ./a.out, we get the following output:

unique_ptr is a smart pointer that embodies the concept of unique ownership. Unique ownership, simply put, means that there is one and only one variable that can own a pointer. The first consequence of this concept is that the copy operator is not allowed on two unique pointer variables. Just move is allowed, where the ownership is transferred from one variable to another. The executable that was run shows that the object is deallocated at the end of the current scope (in this case, the main function): CruiseControl object destroyed. The fact that the developer doesn't need to bother remembering to call delete when needed, but still keep control over memory, is one of the main advantages of C++ over garbage collector-based languages.

In the second unique_ptr example, with arrays, there are three objects of the CruiseControl type that have been allocated and then released. For this, the output is as follows:

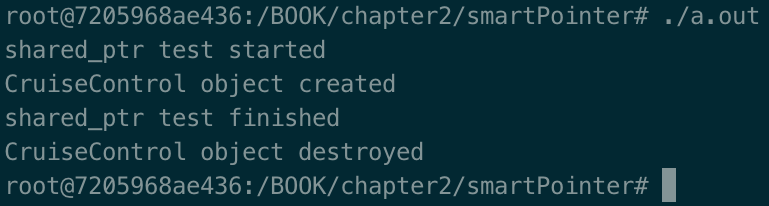

The third example shows usage of shared_ptr. The output of the program is as follows:

The shared_ptr smart pointer represents the concept that an object is being pointed at (that is, by the owner) by more than one variable. In this case, we're talking about shared ownership. It is clear that the rules are different from the unique_ptr case. An object cannot be released until at least one variable is using it. In this example, we defined a cruiseControlMaster variable pointing to nullptr. Then, we defined a block and in that block, we defined another variable: cruiseControlSlave. So far, so good! Then, still inside the block, we assigned the cruiseControlSlave pointer to cruiseControlMaster. At this point, the object allocated has two pointers: cruiseControlMaster and cruiseControlSlave. When this block is closed, the cruiseControlSlave destructor is called but the object is not freed as it is still used by another one: cruiseControlMaster! When the program finishes, we see the shared_ptr test finished log and immediately after the cruiseControlMaster, as it is the only one pointing to the CruiseControl object release, the object and then the constructor is called, as reported in the CruiseControl object destroyed log.

Clearly, the shared_ptr data type has a concept of reference counting to keep track of the number of pointers. These references are increased during the constructors (not always; the move constructor isn't) and the copy assignment operator and decreased in the destructors.

Can the reference counting variable be safely increased and decreased? The pointers to the same object might be in different threads, so manipulating this variable might be an issue. This is not an issue as the reference counting variable is atomically managed (that is, it is an atomic variable).

One last point about the size. unique_ptr is as big as a raw pointer, whereas shared_ptr is typically double the size of unique_ptr because of the reference counting variable.

United States

United States

Great Britain

Great Britain

India

India

Germany

Germany

France

France

Canada

Canada

Russia

Russia

Spain

Spain

Brazil

Brazil

Australia

Australia

Singapore

Singapore

Canary Islands

Canary Islands

Hungary

Hungary

Ukraine

Ukraine

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Estonia

Estonia

Lithuania

Lithuania

South Korea

South Korea

Turkey

Turkey

Switzerland

Switzerland

Colombia

Colombia

Taiwan

Taiwan

Chile

Chile

Norway

Norway

Ecuador

Ecuador

Indonesia

Indonesia

New Zealand

New Zealand

Cyprus

Cyprus

Denmark

Denmark

Finland

Finland

Poland

Poland

Malta

Malta

Czechia

Czechia

Austria

Austria

Sweden

Sweden

Italy

Italy

Egypt

Egypt

Belgium

Belgium

Portugal

Portugal

Slovenia

Slovenia

Ireland

Ireland

Romania

Romania

Greece

Greece

Argentina

Argentina

Netherlands

Netherlands

Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Latvia

Latvia

South Africa

South Africa

Malaysia

Malaysia

Japan

Japan

Slovakia

Slovakia

Philippines

Philippines

Mexico

Mexico

Thailand

Thailand