The components of computational thinking

Solving problems is an iterative process. There are many things to consider at each step. As some challenges are overcome, others will emerge. Computational thinking provides the framework for deciding what step to take next. As with all iterative processes, there will be steps that don’t work out because the solutions you arrive at are unsatisfactory or simply don’t work, but this is all part of the process.

Before we continue, we need to discuss what we mean by a “problem.” For the purposes of this book, a problem is a specific task with well-defined constraints and parameters. The actual nature of the task can be relatively simple or highly complex, as long as it is specific. The constraints can also be broad in nature: they can be managerial (time constraints, deadlines), technical (performance), or domain-specific (physical limitations). The parameters describe the data and other information that is provided in order to solve the task.

The four components of computational thinking are as follows:

- Decomposition

- Abstraction

- Pattern recognition

- Algorithm design

Each step in the problem-solving process will involve one or more of these components, but they are not, in themselves, the steps that one must follow. For instance, some steps will fall into a class of well-known problems with “off-the-shelf” solutions that can be implemented with ease. Other steps will be complex and require decomposition into many smaller problems. Moreover, these components cannot be considered in isolation. One cannot decompose a problem without understanding the essential constituents of the problem or recognizing standard patterns among the noise of contextual information that may or may not be relevant. You must consider all the components at once.

It is sometimes easy to miss the bigger picture when you are solving small and nuanced problems – especially how your solution will interface with the larger system. This could be the larger piece of software in which your solution will live, or the way clients interact with your software. These issues are also part of the problem that you would need to solve, using the components of computational thinking to guide you.

As you gain experience, the number of patterns and standard problems that you recognize will grow, and the speed at which you arrive at useful abstractions will increase. In the beginning, these aspects will be the most troublesome. In the remainder of this book, we will look at common techniques and some standard problems that will allow you to get started with problem-solving. Unfortunately, we cannot simply give you a complete catalogue of patterns and abstractions: if all problems were already solved, there would be no need for a framework for solving problems.

Solving problems is not only an iterative process, but also a dynamic process. Some choices will have implications for the rest of the process and possibly even for previous steps. For example, selecting a programming language, such as C++, will have a dramatic effect on the way you go about designing algorithms, selecting abstractions, the standard patterns available, and the way you further decompose problems. For example, if one solves a problem in Python, one might try to lean on the numerous high-performance libraries, which may or may not provide the exact functionality required. However, in C++, you have more freedom to implement your own high-performance primitive operations.

There will be times when you have to undo several steps of the process, especially while you’re still building experience. The important thing here is to understand that this is a necessary step in the learning process. You must endeavor to understand why that particular line of investigation failed and how to incorporate this knowledge into the next iteration. Don’t be afraid to go back to the beginning (time allowing) and start again. Sometimes this is the only way to make progress.

In the remainder of this chapter, we look in more detail at the four components of computational thinking. For now, we will only discuss the components in general. We will revisit these components in far more detail in later chapters, when we look at real examples and how to apply these concepts using C++.

General advice

Solving problems can be hard, especially when you’re fairly new to a particular domain, language, tool, or working environment. Here is some general advice on how to make this easier and more enjoyable.

- Keep a journal of patterns, abstractions, and other information that you can refer back to when new problems appear. As you get more experience, you will internalize many of these, but there will always be some that you forget about that you might need to call on in the future.

- Seek out small problems to hone your skills. Websites such as LeetCode (https://leetcode.com/) have huge libraries of small problems that are designed to teach specific patterns and techniques. This can help, especially at the beginning when you don’t have your own catalogue to draw upon. The greater the variety of problems that you see, the more you have to draw upon when you’re looking for patterns and abstractions when solving entirely new problems; the problems don’t need to be identical, just similar enough to provide inspiration.

- Talk to colleagues and friends about problems, where this is appropriate. Sometimes the act of explaining a problem can help make it clearer for you and will sometimes help you to solve the problem directly. If you can find a more senior or experienced colleague who is willing to help, then they can share their own expertise with you, which can sometimes help you arrive at solutions more quickly. If no colleagues or friends are available, even talking the problem through with your rubber duck can help – and they are always willing to listen.

A far too mathematical example

Before we go into detail about the components of computational thinking, we should first look at an example where many of these ideas manifest. The example we will use is solving a specific differential equation from elementary calculus. Don’t be put off by the presence of equations in this section. The actual mathematics used here is not the important part; the way that we work through the problem is. Nevertheless, this example is a good choice precisely because of this added complexity; you will sometimes have to operate outside your comfort zone.

A differential equation is an equation that involves one or more derivatives of a function that evolves according to some other variable  . Differential equations are used in many fields to describe how a system evolves depending on various factors. For instance, Newton’s theory of mechanics is described using differential equations (he invented calculus in order to describe the world through these equations). The equation we consider here is far simpler; it involves the first and second derivatives of

. Differential equations are used in many fields to describe how a system evolves depending on various factors. For instance, Newton’s theory of mechanics is described using differential equations (he invented calculus in order to describe the world through these equations). The equation we consider here is far simpler; it involves the first and second derivatives of  , denoted

, denoted  and

and  , whose coefficients are simple constants. The equation is

, whose coefficients are simple constants. The equation is

with some initial conditions  . The objective here is to find an expression for the function

. The objective here is to find an expression for the function  , written in terms of

, written in terms of  , that when “plugged in” to this equation on the left-hand side, gives the right-hand side. To solve this problem, one has to break it down into smaller parts; it cannot be solved directly as a whole (at least not easily).

, that when “plugged in” to this equation on the left-hand side, gives the right-hand side. To solve this problem, one has to break it down into smaller parts; it cannot be solved directly as a whole (at least not easily).

The first level of decomposition involves solving two separate problems: first, we find a solution to the simpler equation where the right-hand side is zero; the second is to find an expression that “displaces” the solution to the first sub-problem to obtain the correct right-hand side. This is akin to fitting a straight line to a set of data; first, you find the gradient and then move the line up and down until it fits properly. (In fact, mathematically speaking, it is exactly this.)

Let’s focus on the first sub-problem, finding the “general solution.” Here, we’re asked to find a solution to the simpler equation

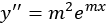

This seems tricky until one realizes that an equation of this kind has solutions that look like  . The derivatives of this are

. The derivatives of this are  and

and  , so plugging those into the equation gives

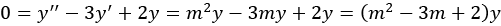

, so plugging those into the equation gives

There are two ways the far-right expression can be zero. The first is that the function  is constantly zero (which cannot be true, since

is constantly zero (which cannot be true, since  ), or if the quadratic equation

), or if the quadratic equation  holds. We have reduced solving a part of the differential equation to finding the roots of a simple quadratic polynomial – a common pattern often taught in high-school mathematics.

holds. We have reduced solving a part of the differential equation to finding the roots of a simple quadratic polynomial – a common pattern often taught in high-school mathematics.

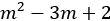

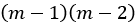

The so-called auxiliary equation  can be factorized into

can be factorized into  , meaning the two roots (the values of

, meaning the two roots (the values of  for which the quadratic equals

for which the quadratic equals  ) are

) are  or

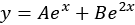

or  . The general solution to our simple differential equation is thus given by a linear combination of

. The general solution to our simple differential equation is thus given by a linear combination of  and

and  , something like

, something like

To find the values of the two constants  and

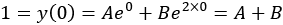

and  , we need to use the two initial conditions. The condition

, we need to use the two initial conditions. The condition  is straightforward to apply, because we just substitute for

is straightforward to apply, because we just substitute for  and

and  in the equation to get

in the equation to get

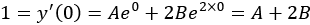

For the second equation, we need to differentiate, but this is also not too hard:

This is a common pattern in mathematics called a system of simultaneous equations (again, often taught in high-school level mathematics). We can solve this by subtracting the former equation from the latter to get  , leaving

, leaving  . (Don’t worry too much if you haven’t seen this before; it isn’t important.) This means our general solution is now

. (Don’t worry too much if you haven’t seen this before; it isn’t important.) This means our general solution is now  .

.

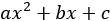

Now we have a solution that behaves correctly, in shape, but it doesn’t solve our original equation. For that, we need to find an “offset” that translates our general solution into the true solution. To do this, we look at the right-hand side of the original equation  . It’s quite reasonable to presume that the factor by which we need to translate our general solution has a similar form to this expression, perhaps something like

. It’s quite reasonable to presume that the factor by which we need to translate our general solution has a similar form to this expression, perhaps something like  , where

, where  ,

,  , and

, and  are constants that we need to find.

are constants that we need to find.

We need to plug our proposed translation into the differential equation, so we need to differentiate it. The first derivative is  and the second derivative is just

and the second derivative is just  . (Again, don’t worry if you’re not following this working; it isn’t important.) Thus, we need to solve the new equation

. (Again, don’t worry if you’re not following this working; it isn’t important.) Thus, we need to solve the new equation

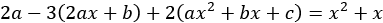

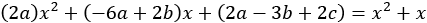

This is yet another common pattern in mathematics called “comparing coefficients” of the left and right. (Two quadratic expressions are equal if and only if each pair of corresponding coefficients is equal.) Let’s rearrange the left-hand side to make this more clear:

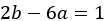

From this, we see that we need each of the equations  ,

,  , and

, and  (no constant term appears on the right-hand side) to hold. Again, we find ourselves back at solving simultaneous equations. To avoid repeating the process, the solution is

(no constant term appears on the right-hand side) to hold. Again, we find ourselves back at solving simultaneous equations. To avoid repeating the process, the solution is  ,

,  , and

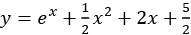

, and  . Putting everything back together now gives the solution

. Putting everything back together now gives the solution

Now for the important bit, reflecting on what we have done. In solving this single mathematics problem, we have actually decomposed it into a number of smaller problems, which required far less knowledge of mathematics. We divided the initial problem into two: the simpler problem (general solution) and then the translation problem (specific solution).

- Within the general solution branch, we recognized the form of the equation (pattern recognition). Finding the roots of the auxiliary equation is another sub-problem – one that is completely isolated from the main problem – and then solving the system of equations to obtain the general solution is yet another. This gives us the form of the general solution, which we must then use the two initial conditions to turn into the actual general solution, yet another sub-problem. We differentiate the form of the general solution and apply the initial conditions to obtain a system of equation. We can apply the standard techniques for solving such a system (pattern recognition) to obtain the true general solution.

- Within the particular solution branch of the problem, we recognize that the translation must have a similar form as the right-hand side of the original equation, prompting us to find the derivatives of a general quadratic expression (two sub-problems where the second is dependent on the first). After plugging these derivatives into the equation, we observed that we could compare coefficients (pattern recognition) we obtain another system of equations to solve.

After resolving both branches, we have to put everything back together to obtain the full solution. This is actually a crucial step, and often non-trivial, especially as the division into smaller problems becomes more complex, and where there are interdependencies.

You might be wondering where abstraction and, to a lesser extent, algorithms come into this problem. Mathematical problems are often abstract in nature; they are already an instance of a larger, specific problem in which the crucial components have been extracted. However, this is not to say there is no room for abstraction within this problem. For instance, finding the roots of a quadratic expression and solving systems of linear equations are both well-understood general problems that appear all over the place. We didn’t mention this explicitly, but the techniques we used (factorization and Gaussian elimination) are general techniques for solving the respective abstract problem, applied specifically here.

The question of algorithm design is trickier to discuss here. Obviously, solving this kind of problem is a fairly standard “algorithm” in mathematics. Indeed, it is taught in many mathematics courses at various levels. It might not be presented in the usual way that an algorithm is presented in computer science, but it is a set of simple steps that one can repeat to solve exactly this kind of problem. Gaussian elimination (the process we used to solve both systems of equations) is a well-known algorithm from numerical linear algebra that is used all over the place. Perhaps you could try and think of a few places where systems of equations like these might appear in your field of work?

Now that we have seen an example of solving a multifaceted problem (albeit from a very different context), we can examine the components of computational thinking in more detail and see how these components work together to derive solutions to new problems.