Design Principles and General Design Planning

Every day we interact with many elements in our environment, for example, turning off the alarm clock, opening doors, greeting our neighbors, or brushing our teeth.

Some of these interactions are positive, whereas other interactions can become really frustrating. We enjoy a fresh drink while relaxing on a sunny day. However, nobody likes waiting in a queue, getting lost in a building, or filling in long forms. Well-designed products and services result in positive interactions.

A saucepan with handles like the one shown in the preceding image is hard to lift when it is full. This is part of The Uncomfortable, a collection of deliberately inconvenient everyday objects, designed by Athens-based architect Katerina Kamprani. Unfortunately, finding uncomfortable objects around us is not that unusual (refer to the source available at https://www.flickr.com/photos/colalife/14624508474/).

The User Experience (UX) of a product or service is defined by how we perceive the summary of our interactions with it. A positive UX is the result of a careful design that is centered on the user needs. This perspective represents a big departure from the classical technology-driven approach that has produced many unusable products throughout history.

This book provides real-word guidance for a user-centered design process. The process described is based on both sound design theory and practical experience. We shall describe the steps to create successful mobile products and provide advice on how to apply these steps in the real world.

In this chapter, you'll learn the following essential aspects of a user-centered design:

- How to adopt a user-centered perspective

- The principles that make a product well-designed

- The basic steps in the design process

- The general challenges you'll find when you apply the concepts learned in the real world

All of these aspects are important for the design of mobile apps, but they are also useful in the design of other products.

Switching your perspective to focus on the user

All products are made for their users. So, what does a user-centered perspective mean, and what is special about it?

The taps shown in the preceding image represent two different approaches in design. The one on the left is the result of a technology-driven design, whereas the one on the right is the result of a user-centered design.

The first tap has two handles--one controls hot water, and the other controls cold water. The two-handle design is dictated by the pipe technology, which comes with separate pipes for hot and cold water. By adding a handle to each pipe you can control everything you need from a tap. The temperature can be adjusted by opening or closing the hot and cold handles to different degrees. However, once you find the ideal temperature, adjusting the flow of water requires to manipulate both handles in coordination to keep the temperature constant. This may not be convenient in many of the uses of the tap, such as filling a glass or washing your hands.

The second tap design starts instead from the user needs. Users need two different kinds of adjustments while operating a tap, that is, adjusting the water flow and the temperature. These independent needs are mapped to two independent movements of a single handle. Move the handle left or right to adjust the temperature. Move the handle up or down to control the water flow.

This makes it easy to keep the temperature constant as the water flow is adjusted, and even keep the preferred temperature every time you use it.

Starting the process from the user needs' perspective allows us to focus on what is easier for the user, as opposed to what is simpler for the technology. The second tap is easier to use, resulting in a better UX when you are washing your hands.

Shifting the complexity from people to technology makes life easier for your users. The drawback of shifting the complexity to technology is that this often represents more work for those building the product on the technical side. In the preceding example, connecting the second tap with the usual two-pipe technology requires a more elaborate mechanism.

People building a solution must understand the importance of providing a good experience to the users. Instead of understanding technology as a limiting factor, we need to understand technology as the magic that could support the best user experience.

Getting organizations to adopt a user-centered perspective

UX design has become a central part of many companies. From big organizations to small start-ups, many companies have adopted design techniques as part of their daily processes. However, the design process is not well-supported in all organizations.

During the initial stages of computing, software was written by developers, for developers. The introduction of mobile devices changed this idea radically. In 2010, the global sales of PCs were surpassed by smartphones and tablets. In the following years, the number of mobile users grew fast, and for many people, the mobile device became their main tool to access the digital world, or even their only one--mobile-only internet users accounted for 15% of all internet users globally in 2017, and represented more than 30% of internet users in countries such as Thailand or Malaysia.

People who were not technology savvy entered the digital world in large numbers, thanks to the wide adoption of mobile devices. People who were afraid to put their hands on a computer mouse previously were suddenly sharing pictures with their friends through social networks. This stressed the importance of making intuitive products that are simple and easy to use. If your product is too complex, users will be eager to look for an alternative.

Mobile devices, such as smartphones, tablets, or smart watches, opened a new world of possibilities and restrictions. Users were now capable of interacting with their devices with natural gestures and voice, but at the same time, they had to use a much smaller screen and care about the device's battery life. Compared to the old days of monochrome text-based terminals, the increasing diversity allowed and demanded more creative solutions.

Creating positive experiences benefits the user, but ultimately it is also beneficial for the organization that creates such products. There is a commonly known story in the design sector that illustrates this:

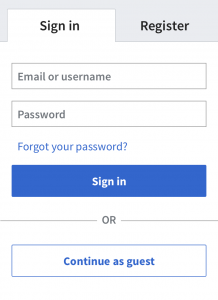

An online shop was forcing users to register with them before buying products. They discovered that most of the users who forgot their password never completed the process. Users were able to request a new password through the usual Forgot your password? link, but they never returned. Since this affected users who had already decided to purchase their products, this meant that many sales were lost. The solution was simple: a button to complete the process without registering. Providing such an option was technically easy, and it resulted in sales going up by 300 million dollars. The difficult part in this case was not building the solution, but identifying the needs of the user and picking a solution that met them.

Design principles

Many different factors contribute to the user experience. Imagine that you are using an e-book reading app. Your experience reading a novel can be ruined by different factors, for example, the use of a tiny font that is uncomfortable on your eyes, an inconvenient way to move through pages that makes you wait too long, or the app forgetting the page where you stopped reading.

Each of these issues is problematic, but each one fails to meet needs of different kinds. A well-designed product responds to user needs at different levels:

- Needs from our human condition

- Needs from general expectations

- Needs from the specific context of use

We'll provide more details on each of those needs.

Needs from our human condition

As humans, we probably experience our world very differently than bats, octopuses, or the fascinating water bears (half-millimeter-long animals that can survive in outer space) do. We experience the world through our human senses; we process information in a visual, auditive, and to a lesser degree, olfactive way--we use our hands to manipulate elements and our voice to communicate.

After a process of millions of years of evolution, our human capabilities have been shaped as a key factor for survival in the physical world. However, when using digital products, our experience is heavily influenced by these same senses and the way our brain is wired to process them.

Understanding how our senses work can help us to design solutions that better fit our natural behavior as humans. For example, our peripheral vision allows us to identify movement at the edges of our vision field. Although we cannot recognize shapes or colors perfectly in that area, we can quickly notice any movement. The evolution theory suggests that this may have been useful to our primitive ancestors to quickly react to predators.

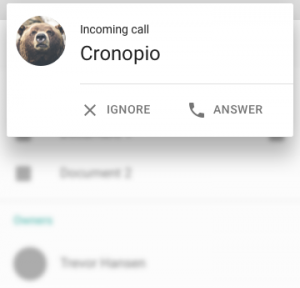

Nowadays, we use our peripheral vision to note the notifications that many apps show us as moving boxes at the top of the screen of our mobile devices. Designers of such interaction patterns took advantage of our capability to detect movement in the surroundings of our focus area. They decided that notifications should appear by moving in--as opposed to fading in--so our eyes notice them more easily.

We have intuitive reactions to different stimuli. Even the most basic aspects--such as shape or color--bring their own implicit meaning when we process them. We describe these effects as their psychology.

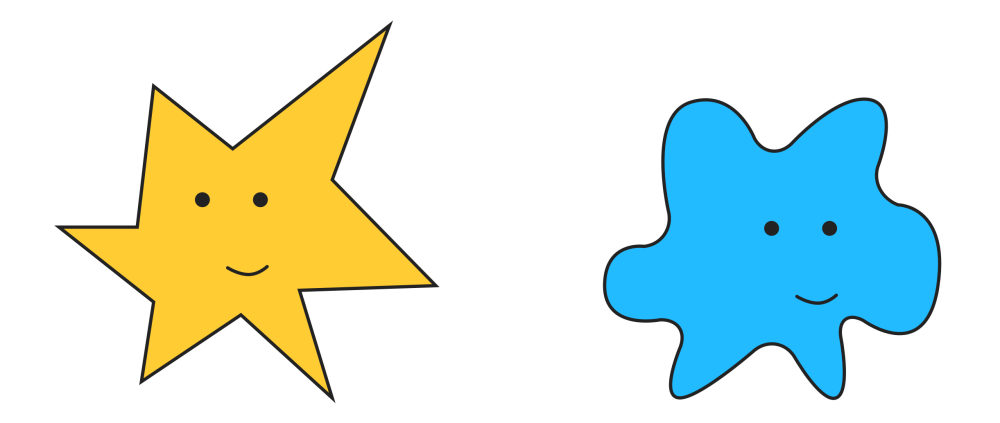

A simple experiment shows the psychology of shapes in action. When people are shown two apparently random shapes like the ones in the subsequent image and are asked to name them as either Bouba or Kiki, most people will pick the same names for the same shapes. Most people will associate the rounded shape figure with the Bouba name and the spiky figure with the Kiki name.

The psychology of shapes can affect many elements in the design of your app. For example, the use of straight corners or rounded corners in the interactive controls can help to provide a more serious or a more playful feel to it.

The psychology of color is another widely researched area. Technically, color is just a representation of light at different wavelengths. However, when classifying colors, we use temperature (warm or cold colors) based on some of their associations. Marketing and branding has studied how these associations affect the sales of products and the perception of the companies selling them. While red is associated with excitement, blue is associated with relaxation.

These implicit reactions should not be the main force driving our design decisions, but we should be aware of possible contradictions that can confuse users. These confusions may occur when the meaning we try to convey contradicts the implicit meaning of those elements. For example, a red text will catch the user's attention, so it may not be the best choice for an e-book app as the main text color for reading a book comfortably.

Beyond the perception of individual elements and their properties, it is interesting to think about how we understand them together to form our experience. Gestalt (form in German) psychologists studied human perception and defined a set of properties that have been influential for many designers. They described how our brain identifies individual elements and is eager to find meaning of those elements. In particular, gestalt principles for grouping have many applications in the design of digital products.

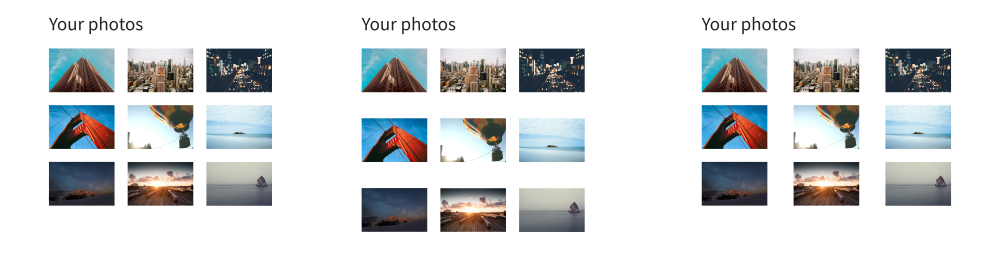

For example, the law of proximity dictates that elements that are close to each other are perceived as a group. By adjusting the space around elements, we can control how those are related to each other by our brains. Consider a photo gallery app; by adjusting the relative distance between pictures, we can make all photos look like a single group (keeping a uniform separation) or break them into rows or columns (increasing the vertical or horizontal space to guide our eyes).

Other gestalt principles suggest that our brain also groups together elements that look similar (law of similarity), move in the same direction (law of common fate), are connected without abrupt overlaps (law of continuity), or form a simple pattern (law of good form).

One of the main underlying ideas of these and other gestalt principles is the tension between similarity and contrast. This tension can occur in different dimensions (space, proportion, time, motion, and so on) and contributes to our perception of order.

When designing a product, we want to present physically connected what is conceptually related. Adjusting these different properties in the right way allows us to guide the eyes and the brain of our users to understand such organization as intended.

The Human Computer Interaction (HCI) community has been modeling many different human behaviors. For example, Fitt's law is a predictive model for human movement. In short, it states that the time it takes to hit a target (such as tap on a button) depends on how far away the target is and its size. This means that a small button far away will be harder to access than a big button you can access nearby.

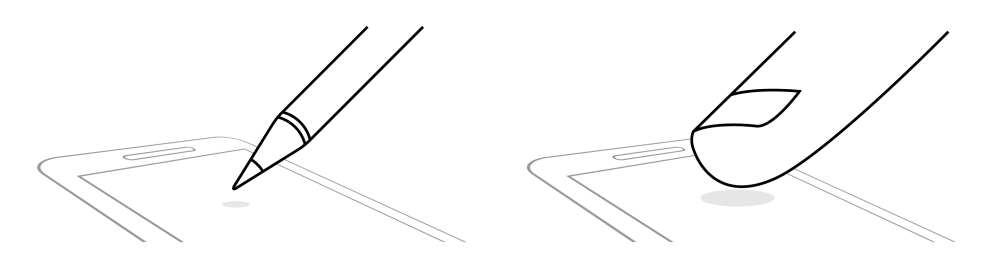

The size of the targets, such as buttons and other controls, have evolved in mobile design thorough history, affecting their ease of use. The first mobile devices adopted the stylus as a pointing device and required users to be precise when choosing their targets. The iPhone challenged the idea that a smaller screen required smaller targets. Increasing the size of the targets made it comfortable to use with fingers, resulting in more intuitive interactions.

Our bodies and brains are the platform we ultimately run our products on. There are many disciplines and much research that provides us with valuable information about this platform. You don't need to be an expert in psychology, medicine, or biology to design great products, but understanding how humans work at their basic level will help you to design better for them. Being curious about human nature and observing people's most intuitive and visceral reactions can help you to identify relevant behavior that, being a core part of our nature may otherwise go unnoticed.

Needs from general expectations

Even if our body and brain are capable of doing many activities, it does not mean all of them are convenient, comfortable, or pleasing for us. Regardless of the specific type of product, users have general expectations when using them. Failing to meet those expectations when designing our products will negatively affect the resulting user experience. Users will be confused to see a product not behaving as they expected, which is breaking the principle of least astonishment.

Each interaction the user performs with a product requires some mental effort. This mental effort is often referred as the cognitive load. For example, a navigation app can ask your destination during your vacation trip in different ways. It would be easier for you to indicate the destination by the name of the place (Eiffel Tower) rather than the specific address (Champ de Mars, 5 Avenue Anatole France, Paris) or using the exact coordinates (48° 51' 29.6" N, 2° 17' 40.2" E). The cognitive load could be reduced further if the app were capable of ignoring potential typos, allowed voice input to just say the destination, or could suggest the destination in the first place, anticipating your needs.

A well-designed product should demand as little effort from the user as possible, reducing the points of friction where the user has to stop and think, reorient, or gets confused. Reducing friction often requires moving most of the complexities--such as translating the name of a place into coordinates--from the user into the computer.

The effort to use a product can be divided in two stages--understanding how the product works and operating it. Design considerations are key in both stages.

Explaining how a product works should be the job of the product itself. Designing a product that is obvious to use is essential since no one is going to read the instructions.

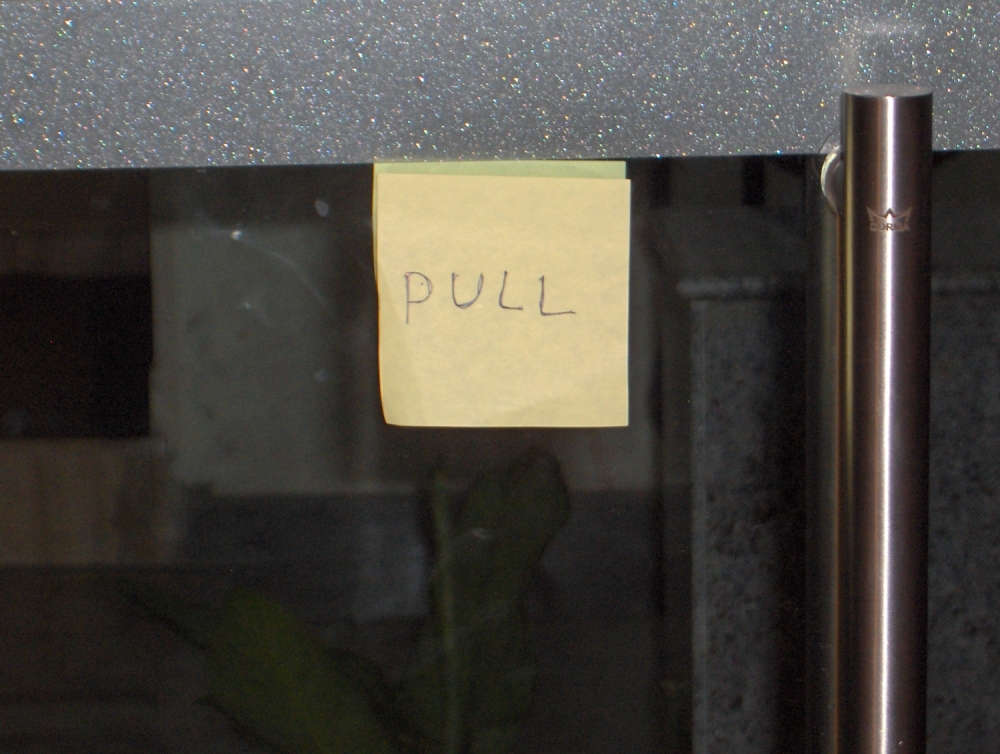

Donald Norman described the elements that communicate the possible actions of an object as affordances. Door handles are a classic example of affordances. They are placed at the hand reach and shaped to be manipulated by our hands. They are the way for the door to tell us how to open it. When affordances are applied wrong, they result in confusions about the possible actions. As a result, people find themselves pushing a door that should be pulled instead--those cases of badly designed doors are known as Norman Doors, named after the well-known designer.

Affordances can use different properties to suggest their intended use such as shape, position, color, or movement. That helps users to interpret their meaning, but their meaning is also reinforced by previous experiences. The direct or indirect associations with previous uses of similar cases helps with the learning of new ones. Products do not exist in isolation, and the use of existing products will influence our expectations of new ones.

The digital world also has its own conventions that millions of previous products have help to establish. For example, many users will identify an "X" icon to represent an action to close or discard.

Metaphors can help users connect the dots between a known concept and an old one. The digital concepts of desktop, folder, or windows rely on some of the aspects of their physical counterparts. A shopping app can use a shopping cart icon to signal the place where your selected products are.

However, we need to be careful and avoid mimicking the original concepts. It won't make much sense to use a 3D recreation of the shopping cart where you need to make the space to place each product in the cart as you would in a real supermarket. Avoid transferring the limitations of the physical world into the digital one. The digital space is better suited for many actions such as finding the products you bought last week. You don't want to follow a metaphor so literally that it limits the possible solutions.

Design guidelines capture important conventions to consider when you design for a specific platform, organization, or family of products. In this way, your solutions can reuse concepts that are familiar to users in the exact way they are used to interacting.

Breaking conventions may be needed at times, but it should be done only for a really good reason. We need to make sure that the benefit provided to our users is much greater than the potentially negative effects of possible confusions.

Social and cultural conventions also have their influence on what people expect from products. A hand gesture that means approval in one culture can be an offensive gesture in another, when found as an icon. Similarly, languages bring their own conventions. Concepts associated with directionality will be represented differently depending on the language direction. For example, a forward, next, or reproduce action in English--a left-to-right language--can be represented with a triangle or arrow pointing to the right, whereas it needs to point to the left for languages, such as Arabic, which are written in the opposite direction to keep its forward action.

In addition to understanding how products work, we want them to require minimal effort when they are used. The following principles contribute to a positive user experience for all kinds of products:

- Require minimal intervention: The fewer steps we need to solve a problem, the better. Our designs should avoid unnecessary steps for people when using our product. This can be supported by the following different strategies:

- Allowing flexible input: Information can be provided in many different ways. Some people use spaces, parenthesis, or dashes to group telephone numbers or monetary amounts in a transaction, others do not. Instead of imposing a specific format to meet the needs of the technology, allow your users to provide the information in all the ways that are most natural to them.

- Providing smart defaults: When asking users for information, we should avoid open questions, and provide options instead. Recognition is a much simpler mental process than recall from memory. Thus, anticipating possible answers will save time for the user. If any of those options is likely to be what the user needs, setting it as the default would save time in most cases. For example, navigation apps can assume that your current position is your starting point. That is not always the case, and you may need to change those defaults, but overall it will avoid an additional step to go through most of the time.

- Support direct manipulation: For a long time, the mouse was one of the most common input devices. Users moved the mouse on their desk to move the cursor on their screens in order to act on a digital object. The arrival of touch screens allowed users to tap the element directly, reducing indirection steps. Indirection steps require users to make mental efforts to go through them. For example, it is simpler to use a hand gesture to zoom a picture than accessing a separate zoom menu that is disconnected from the picture it affects.

- Inform users in relevant terms: Users want to know what is happening when using a product, but this feedback needs to be meaningful. Some aspects to consider:

- Make users feel in control: Regardless of the level of automation a product can provide, users want to feel in control. A user trying to send a message to a friend will be more comfortable when they are sure that the message is sent and has reached the destination. This confirmation can happen in many different ways, from a simple visual cue to a more explicit feedback text. Choosing the right level of prominence for feedback according to each case will allow users to feel in control without the system being perceived as annoying.

- Explain by comparing: Information is better understood when compared. During a car trip, knowing the distance to the destination can be useful. This distance is useful in your favorite distance unit--miles or kilometers--but it is even more useful when presented compared with the car speed as the time to reach your destination. Given a piece of information, it is important to identify the purpose it serves for our users in order to decide which is the most meaningful representation for it.

- Communicate in the user's terms: The closest we represent concepts to the way users understand them--what is referred to as the user mental model, the more fluent their interaction will be. We should avoid messages that refer to internal aspects of the system or using technical jargon. A user looking for a taxi will be confused to hear that no records were found. It is easier to understand instead that no taxis are available in the nearby area.

- Don't waste the user's time: Time is a precious resource. When helping users to solve their problems, they will always appreciate solutions that require them to use as little time as possible. These are some relevant concepts to be considered:

- Keep tools at hand: Providing the tools people need where they need them helps the user to avoid spending time looking for them elsewhere. After you call a telephone number that is not in your contacts, it is convenient to have an option to save it as a new contact. Identifying the next logical step and looking for ways to facilitate it will help you come up with these convenient shortcuts. Separating actions (the operations you commonly use to manipulate information) from configuration (the preferences you have and rarely change) also helps users to have the most needed options at hand.

- Performance: Nobody likes waiting. We should aim for our products to respond to user interactions as fast as possible. Anticipating the user next steps, caching, and other technical optimizations can help you to keep the user interactions under a reasonable response time. Regardless of the real time it takes to complete an action, even more important is how long the wait is perceived by the user. The perceived performance can be improved in many ways. Using placeholders similar to the content that will be loaded or communicating long waits with an adequate loading indicator will help the wait to feel shorter than what it actually is.

- Reduce interruptions: Asking the user to stop what they are doing will force them to switch context and break their flow of actions. Modal dialog and alerts can become annoying. We should aim to communicate relevant circumstances, such as the username proposed not being available or the internet connection being lost in a non-blocking way. Make your users aware of the information, but let them to decide when to act about it. Similarly, when waiting for some information, keeping the blocked elements to a minimum will help to reduce interruptions. For example, on a map application, it is convenient to make it still possible to manipulate the map--moving or zooming it--while the map tiles are being loaded with images.

- Avoid mistakes: People feel bad when they make mistakes. Your products should not harm the user or make them feel stupid. These are some possible approaches:

- Make it impossible to use it incorrectly: Ideally, a product should be designed in such a way that it is impossible to use it improperly. For example, using the appropriate controls, you can communicate that the range of dates for your hotel reservation can only include future dates. Preventing accidental side-effects and confusing errors contributes to creating an environment of safe exploration, where users are welcome to move around and find their way without the fear of messing things up.

- Avoid dead-ends: Users should always have a way forward to achieve their goals. We should avoid putting them in situations where there is no apparent way to move forward. For example, if there are no results for a user search, some alternatives can be suggested based on similar results--similarly spelled results--or you can provide alternative ways to find content--such as browsing by categories.

- Alleviate the unavoidable: In cases where mistakes are unavoidable, our product can consider ways to correct or alleviate those issues. For example, a network failure can be fixed by retrying the operation automatically without bothering the user. If the connection remains unavailable for a longer time, informing about the issue and keeping the pending changes locally to be saved later would help. In any case, never blame the user. Avoid messages that can be understood as an error being the fault of the user, since users only do what the system lets them do.

There are many general design and usability heuristics and pattern libraries and guidelines. These provide recommendations on important aspects to consider when designing positive interactions for all kinds of products. Following them will help your products to be more usable. However, these are not enough to guarantee that your solution will satisfy all the needs of your users.

Needs from the specific context of use

In addition to our needs as humans, and our general expectations as users, there is another set of needs that are specific to the context of use. These are defined by the purpose and goals of people using a product.

The video editing needs of a casual consumer documenting their last vacation trip are very different from those a professional filmmaker may have for a film. Therefore, a video editing app will be very different depending on which of these audiences we design the app for.

Conversely to the previous sets of needs, you can only learn about context-specific needs on a case-by-case basis. The users you will be designing for will be very different from yourself. There is no specific advice that applies to all kinds of products. Nevertheless, the design process will help you with the mindset and provide a set of activities to guide you to learn more about your users, identify their needs, and solve their problems.

In order to solve a user need, first you have to recognize what a need is. This may sound simple, but the distinction between a need and a solution is not always obvious.

Imagine that you live in a town next to a river. The town mayor calls and tells you: "We need a bridge. Can you design one for us?". At that point, you may be tempted to start thinking on how to design the perfect bridge. However, a bridge is not a need, the real need is to cross the river.

A bridge is just one of the many possible ways in which the underlying need of crossing to the other side of the river can be addressed. Other possible ways to cross the river are creating a ferry service, a cable car, or a zip-line. Failing to identify the underlying need limits the possible solutions you may consider.

Limiting the range of possible solutions too narrowly can lead you to suboptimal solutions, ignoring interesting ideas and limiting your capabilities to innovate. Asking "why?" is a good way to identify the underlying needs.

Asking why allows you to make the problem scope wider--maybe the town inhabitants don't need to cross the river if they have a food delivery service or if the course of the river can be diverted. The different constraints, priorities, and conflicts will limit the scope of the problem and will inform the selection of possible design solutions.

Design rarely happens in an environment with unlimited resources. There are many constraints we need to take into account instead. These constraints may come from different areas such as budget, law regulations, social conventions, and more. It is part of the designer's job to understand and consider those when looking for solutions.

In a constrained environment, not all needs have the same priority. It is important to consider how they impact the user since we'll have to support them at different levels. The model described by Noriaki Kano defines different patterns of user satisfaction:

- Must-haves: This indicates the basic needs users expect to be supported by a product. Failing to properly support these generates frustration for users. However, there is a certain point where improving the support will have diminishing returns. For example, users of a navigation app will expect to have some zoom capabilities. Providing no zoom at all would be frustrating for users to pick their destination; however, they don't need the app to compete with a NASA telescope in zoom capabilities and additional levels of detail won't improve the user experience significantly.

- Linear needs: This indicates the needs that add more value as they are better supported. In our navigation example, the time it takes to find a route will impact the user experience. There will be a point where the time is considered too long to be usable, and another point where it will be considered fast enough, but the faster it finds the best route, the more value it will bring to the user.

- Latent needs: These are needs that users do not realize they have. For products that don't support them, users won't miss them. Therefore, they don't get frustrated by their absence. However, as soon as a product solves those needs, they will greatly benefit from the new possibilities. A navigation app that suggests good places to eat when lunch time approaches can be helpful for many users, but it may not be something they ask for if it is not common in other apps. Latent needs are hard to discover since users cannot easily articulate them. Research techniques will help you to identify behavior patterns that can signal these needs.

- Indifferent aspects: Some aspects from a product may not be serving any particular user need. You would want to identify and remove those.

When designing a product, it is common to find conflicting needs. Users of a camera app may need it to be quick to shoot with. However, they may also need a high degree of control to adjust many different parameters. Design is about finding optimal balances between conflicting interests. Some useful considerations when dealing with conflicting needs:

- Adjust the prominence level based on frequency and impact: When satisfying multiple needs, the designer acts as an orchestra conductor. Supporting in a more prominent way--bigger, in an easier to find location, with a contrasting color, and so on; these needs occur more frequently or have a bigger impact on the user. Functionality, such as the shutter button of a camera, which is often used, should be more prominent than controls that are used infrequently or have a much lower impact.

- Identify what to optimize and what to just allow: When you cannot satisfy multiple needs to the fullest extent, you need to identify the ones you want to optimize your product for. Consider how to fully support the essential needs while still providing basic support for the secondary ones. It is often better to prioritize support for the critical needs at the expense of other less critical needs rather than providing mediocre support for all of them.

- Keep things simple: Between two solutions that solve a given problem well, you should prefer the simple one. Simple solutions are easier to understand and operate. Don't be afraid to drop some capabilities in favor of supporting the main needs better.

Solving design problems requires a deep understanding of the context of use. Every problem is different. Fortunately, the design process can be applied to different contexts.

The process we present in this book will guide you through the steps to identify different user needs, find solutions for them, and verify that your ideas work in practice. The great Italian designer Massimo Vignelli (more about his perspective on design can be found in his freely available Canon at http://www.vignelli.com/canon.pdf ) said, "If you can design one thing, you can design everything."

General design planning

The design process can be summarized in three simple steps: learn about the problem, explore possible solutions, and verify the solutions that work in practice.

The following chapters will elaborate on those steps to detail specific activities that can help you move through the process:

- Research: You cannot solve a problem if you don't understand it well. Learning about your users, their needs, and motivations is essential in order to solve their problems. Research techniques will help you get this knowledge and analyze it.

- Explore ideas: Given a problem, there is no single possible solution. Problems involving people normally have many potential solutions. Innovative ideas can be found quickly with an exploration process based on sketching.

- Mobile patterns: In order to meet the basic expectations of your mobile users, you'll need to follow the conventions on the different mobile platforms.

- Detail your solution: Communicating your ideas clearly is essential in a team. Design tools allow you to move your idea from the abstract to a more detailed representation.

- Prototyping: Design solutions are not static. To evaluate your ideas, you need to recreate how users interact with them. The prototyping process allows us to simulate our ideas without the effort needed to build them. Picking the right tool for the job is also part of the process.

- Prototyping with motion: Visual tools that embrace the concept of time are powerful prototyping tools. They provide control on how to communicate with motion by defining transitions and animations with great detail.

- Prototyping with code: Another perspective of prototyping is using code. Translating the prototyping concepts to code is a powerful approach to prototype your ideas.

- User testing: You don't know whether things work or not until they are used in practice. If you are able to recreate how an idea will work with a prototype, you can put it in the hands of a user and learn how well it will work.

This process is iterative in nature. Although it is described as a sequence of steps, you'll experience many different iterations for different parts of the product. Moving back and forth is totally expected and the results of each step will inform the next move.

For example, based on the results of testing a prototype of the general idea for your app, you can go back to learning about the problem, exploring more solutions on the drawing board, looking for a completely different approach, or further detailing your existing solution focusing on a specific aspect.

As with all chapters in this book, a Being pragmatic section will provide some advice in applying the design process in practice.

Being pragmatic

User experience design sounds like a simple process. Ideas such as understanding a problem before trying to solve it may not sound very radical. However, the number of badly designed products we encounter every day shows that this process is not always well applied in practice.

There are many challenges when following the design process in the real world. You may be tempted to consider these to be political issues caused by someone else or the result of a general lack of design culture in society. However, that perspective is not going to help in practice. Applying a proper design process in a team requires the efforts of the team to understand the benefits. You are in charge of helping them to change their mindset for the process to work in practice.

Design is not about making things look nice

Design is a process of finding solutions, and it starts before the problem is clearly defined and understood. However, many people identify design only with the aesthetic aspect of an object. They expect designers to come at the end of the process to make an existing product look good with few cosmetic adjustments. Although aesthetics definitely contribute to the user experience, that is just one component, and it won't help to fix the big usability issues in your product if those already exist.

You need to make sure that you are involved in a project from the very beginning. Emphasize in your team the need to understand the problem well before jumping into a solution in cases where they are already considering a predefined path of action. If you arrived late in the process, it is still useful to present alternative solutions. This will illustrate how design can be more valuable at the beginning of the process the next time.

Users are not able to tell you what they need

He was referring to the latent need for better transportation and the way people communicate those needs based on the solutions they already know, as opposed to potential solutions that do not exist yet, such as a car.

People are not good at describing their needs or predicting their future behavior. That does not mean you should be arrogant and ignore what people tell you. This means that you get feedback from them based on observing actual use, and make an effort to understand which are the underlying issues behind a user suggestion.

You (or your team) are not your users

People in your team, including yourself, may project their own needs or personal preferences onto the products. These opinions may not help solve the real needs of your users, and often lead to fruitless discussions among people with different preferences.

In these situations, it is important to change the perspective of the conversation--instead of discussing about what people in the team like, focus the conversation on what will work for your users. This encourages people to connect their feedback to the product goals and provide more context.

A complaint such as I don't like this drop-down menu is not very helpful. Framing it as I don't think this drop-down works since users are provided with too many options when making a quick decision brings more context and it is presented as an hypothesis that can be checked--you can ask for a situation in which such a problematic case would manifest, and recreate this when testing. This perspective change helps to focus on the user goals, and turns feedback into opportunities for learning more about your users. Making sure that the team regularly views real users using your products and prototypes will help with this shift of perspective.

User experience is not a list of features

Products are often described as a list of their features. However, that does not reflect the aggregated experience users have when using all those features combined in a product.

A great feature may be worthless if users cannot find it or they get confused when trying to use such a feature. Thinking only about adding more and more features often leads to ignoring how easy or hard is for users to use them.

Similarly, teams may be willing to cut corners of a product for an initial version or a Minimum Viable Product (MVP). A complete product with a small scope is preferred to an incomplete product with a wider scope. A small focused product is more useful than a bigger half-baked solution. Addressing many different needs poorly is not going to generate a very positive user experience. At the end of the day, a bike is much more useful than half a car.

Your goal is not to make your client or boss happy

As a designer, your goal is to find the best possible solution to a user problem. You are giving voice to the users of the product, who otherwise would have little room at the table.

While having a positive working relationship with clients and teammates is good, it is your responsibility to flag anything that negatively affects the users even if that leads to some serious conversations. Some of the user needs may conflict with the needs or interests of your organization. While it is part of your work to consider the different constraints such as production costs when solving a problem, you also need to make the organization understand that going against the user interests won't be good for the organization in the long run.

For example, an airline website that hides the option to opt-out from travel insurance to trick users into getting it will get some monetary benefit in the short term, but it will negatively affect the trust the users have with the brand in the long run. Tricks that make products hard to use on purpose are known as dark patterns, and you should never use them.

Summary

In this chapter, we introduced the importance of adopting a user-centered perspective when designing your products. Designing a positive user experience is the key to successfully addressing the needs of your users.

Throughout the chapter, we described different types of needs based on our human condition, general expectations, and the specific context of use. We introduced a set of basic design principles for you to consider when addressing these different types of needs.

We provided an overview on the general steps of a user-centered design process and provided advice on how to apply the process in practice. Each of the following chapters will focus on one specific step in this process.

In the next chapter, we'll present key research methods for you to discover, understand, and capture the specific needs of your users. Your understanding of the problem will inform many of your design decisions for your product. Having a deep understanding of the user needs will allow you to meet those needs more accurately.

Download code from GitHub

Download code from GitHub