Chapter 1: The Business of Composing for Clients

In this chapter, you will learn about the business of composing music for clients. We will discuss how to land a job composing music so you can get started, how to prepare for meetings with clients, and how to obtain actionable project requirements. This way, you'll be able to strategically satisfy your clients every time.

We will discuss planning a film score and useful methods for collaborating with other musicians so that you can work efficiently. Finally, we will discuss how to collect music royalty revenue so you can earn passive income from your compositions.

We will cover the following topics in this chapter:

- Landing your first composing gig

- Preparing for meeting clients

- Planning a music score

- Collaborating with others

- Advice for avoiding rookie mistakes

- The day-to-day tasks of composing

Landing your first composing gig

Landing a job creating music for clients is not like getting a regular office job. Music jobs are rarely posted on job boards and the interview is different from traditional interviews. This is for a good reason. The task of composing music requires a very specific set of traits that are not easily evaluated by reading a resume or asking traditional interview questions.

Let's take a moment to put ourselves in the client's shoes. Imagine you're a director who has just finished creating a movie. You've spent time carefully revising a script, running casting calls to find actors who look the part and have the right chemistry, scouting filming locations, and planning shoots, and are finally in the process of editing the footage in postproduction. You now need scenes in your film to hit certain emotions, and you need music that's tailored just right to do this.

After expending all that effort trying to make sure every detail fits the film precisely, do you think you would hire someone you've never met to make the music? Perhaps if they're famous with a solid track record you might. But if you haven't heard of them before, then you're going to need some evidence to prove they can deliver. You need to trust that whatever music is composed will be aligned with the overall style of the film. That information can't be obtained by reading a resume or asking traditional interview questions.

When a client needs someone to compose music for their project, the first thing they do is think about their current connections. Is there someone they already know who can do the job? With the exception of music videos, the music doesn't come first—the project comes first…which means the music is often an afterthought. An important afterthought, but if there is no project, then no one is asking for music.

What does this mean? It means that the best odds of you landing a music job is being already known by the people creating projects. Ideally, they should know about you long before they start looking for someone to compose music. If you want to compose music for films, you should be hanging around with people who are actively making films. If you want to compose music for video games, you need to be hanging out with people who are making video games.

Figure out which films or video games are getting created locally and find ways to enter those communities. Learn everything you can about the projects getting created. Ask questions, explore their past projects, and volunteer to help with their projects in any way that you can. The more you can do to establish your presence, the more natural it will be for you to compose music for them. Of course, you also need to establish yourself as a capable and professional music composer.

How to establish yourself as a professional

What should you do before you start applying for composing jobs? You should do everything you can to establish a brand portraying you as a capable music-composing professional. There are lots of musicians out there—only a subset of them can make original music for other people in a professional setting. You want potential clients to know that you are part of that special group.

Many good live musicians don't have the skills to be good composers, while many composers aren't great live musicians. There's overlap for sure, but there is also a separate composer skillset that is required to do composing that is much more than being good at playing music. Not to worry, though—this book will teach you everything you need to know to get your skills up to par.

Here are a few quick steps to make you appear instantly more professional to potential clients:

- Have a professional-looking music website that displays your music and music-creating services. The website should at a minimum have samples of your music, a short biography about you, and your contact information.

- Have your past music easily accessible so you can provide it at a moment's notice. I personally use SoundCloud as my site of choice when I need to provide links to my portfolio. SoundCloud is a website where you can upload your music, and listeners can listen to it without having to log in.

To learn more about SoundCloud, visit https://soundcloud.com.

- Get business cards. Even though people don't need business cards anymore when contact information can be plugged into your phone, a business card makes people think you're serious about what you do. Business cards are also convenient to hand out at events. If you don't have business cards already, go make some.

- Create an email account dedicated to music business-related activities. Make sure your email address sounds professional.

- Create a Facebook page dedicated to your music-related business. When you share a post saying that you made music for a project, it acts as free advertisement for you.

- Even better than a Facebook page, create a local community group or Facebook group related to your music business. When I was in university, I wanted to create films, but there weren't any film-making groups on campus. So, I created my own. This helped to foster a community of filmmakers and gave me opportunities to get started creating my music portfolio. I was also lucky enough to enroll in classes about creating video games, which gave me my first shot at composing for games. If you're a student, you have a golden opportunity to organize student groups around music/films/video games. There are always lots of like-minded people eager to join as members. Make the most of these student opportunities while you can.

Next, let's talk about networking.

How to network

If you want to compose, you should be going to meetup events where films and games are being planned. Find out where the producers, filmmakers, actors, and writers are gathering.

If you're interested in finding existing groups or creating a local community group, consider checking out the following website: https://meetup.com/. Meetup is a website that helps you find or host local events. Sometimes, you can find film- or video game-related events near you. If they aren't any nearby, consider starting a Meetup group yourself.

Another good place to start networking is at amateur film festivals, where there are always parties for meeting and greeting. Meet and greets at festivals may not be specifically listed on the event brochure. If so, ask around at the event, and you'll invariably discover that some members are going for refreshments afterward. At meet and greets, give your business card to everyone before you leave, and get their contact information. Do everything you can to make friends with the people who are the project creators.

After the event, send a text or email reminding people of who you are, something relevant to the conversation you had with them, and that you'd like to follow up. Perhaps send them a link to a song you made. Then, routinely follow up with them on a regular basis by calling or sending them a message to keep up to date with their activities. I have always found the atmosphere at amateur film festivals to be inclusive and welcoming to newcomers, so if you're new, this is a good place to start.

It's unlikely that meeting someone at a meet-and-greet event will land you a job outright. I've never seen that happen at a first meeting. It's always a series of bumping into the same people at several events until people eventually begin to recognize your face. Each time they see you, it becomes easier to make yourself relevant to their project. Then, when you feel it's time, mention you have some music you'd like to send to them for consideration.

Don't know what to do at these events to get started when networking or how to break the ice? Here are some safe conversation starters:

- I find it's often good to play the new-in-town card. People like to introduce new people to events. You can ask what the host likes about the event and how they got into it and ask who's attending and whether you can be introduced to them. Even if you've been to a particular event once or twice before, sometimes it still helps to pretend that you'd like to be introduced around as this can make it easier to enter into a new circle.

- What project are you working on at the moment? Be genuinely curious and find out any details that you can about their project. People like to brag. When they brag, you can learn a lot if you listen.

- How did you get into ____? For example, directing, producing, writing, game making, and so on.

You can volunteer to help organize existing networking events; this is an easy way to get your foot in the door and make yourself relevant. It might even give you the opportunity to show off some of your past work. Perhaps you can find some excuse for a demonstration to show off your past projects. If there's some way you can make a short presentation, it's a guaranteed way to get your face recognized at an event.

What if I don't already have a portfolio of music?

In order to get a composing gig, you usually need to have some previous music-composing experience. People want to see what you've created in the past before they can trust you. In the beginning, it may feel like a nasty loop you're stuck in. You need work to get experience, but you need experience to get work. What if you don't have any past work to point at? Then, you may need to create some work for yourself. Sign up to create films for amateur film festivals. Go to these film festivals and try to recruit people who are interested in creating a short film. These people may turn out to be looking to hire a composer further down the road or—more likely—happen to know an event to attend or someone who happens to be working on a project.

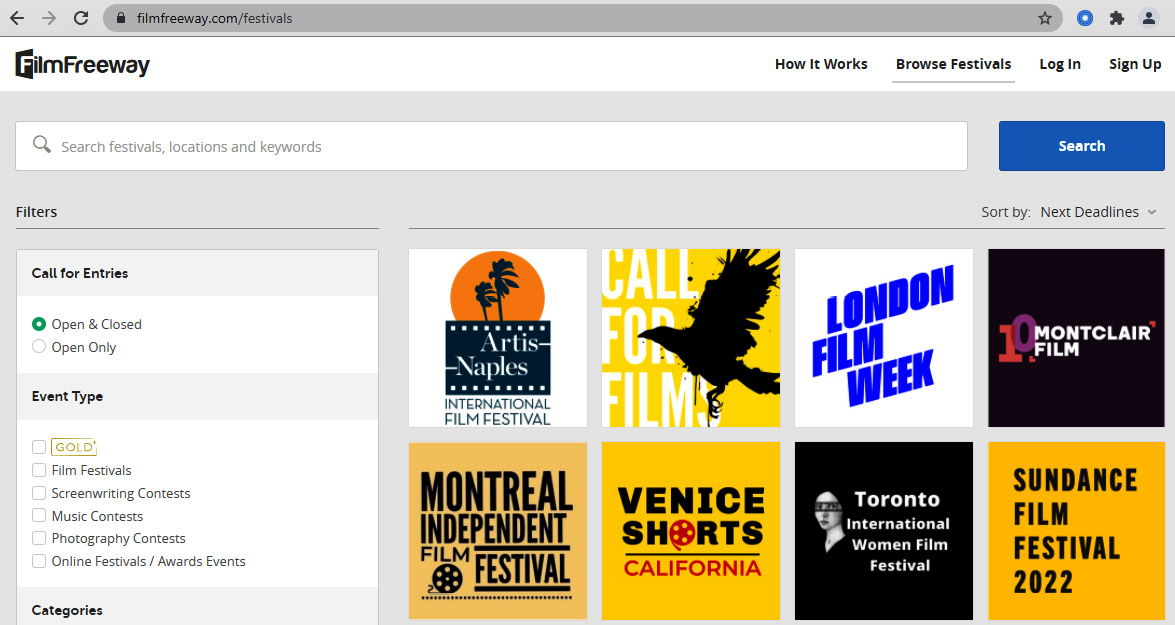

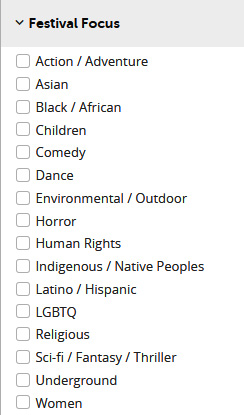

There are lots of film contests that are open to the public. If you're interested in submitting films to film festivals, the following website lists festivals, contact information, and submission criteria to enter into them: https://filmfreeway.com/. You can see a screenshot from the FilmFreeway website here:

Figure 1.1 – FilmFreeway

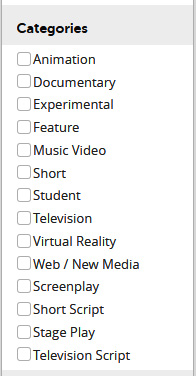

The FilmFreeway website has filters that help you narrow down the type of film that you want to participate in. You can filter for entry fees, countries, dates, and submission deadlines. The website breaks down film festivals into the following categories to make it easy to find the type of film you're interested in:

Figure 1.2 – FilmFreeway Categories

In addition to Categories, you can also filter by the film's genre/focus:

Figure 1.3 – FilmFreeway Festival Focus

If you're looking to find film festivals to participate in, FilmFreeway is an excellent resource.

In recent years, I've found Facebook to be a useful tool for cold calling. On Facebook, you can join Facebook groups dedicated to your local film- and game-making community. In these groups, you can see postings from people networking and making film role-call postings. I've found that messaging people in these groups can sometimes lead to gigs or referrals. Even if a post is only to recruit actors, applying with an email describing the services you offer can sometimes get your foot in the door. On several occasions, I've found that applying as a composer to an actor role call has led to an opportunity.

When you find a contact who is in need of music, you need to find a way to show that you are the best person for the job. If you send a generic resume, you're probably not going to get the job. Before applying, research everything about the project you can find. When sending an initial message to the client, explain how you can create music that is tailored to their project. Then, go and create some demo music that you think would fit their project. Best-case scenario—the creator loves the demo music, and you have a starting musical idea to build off of. Worst-case scenario—you created some music for free that you can add to your portfolio. But if you're reading this book, it means you love making music, so you should think of this as fun rather than being a burden. The goal is to get a job making music. How do you get that job? You make music. See, you're already winning!

A worthy mention is the following website: https://soundbetter.com/. You can see a screenshot from the SoundBetter website here:

Figure 1.4 – SoundBetter

The SoundBetter website allows you to hire or sell music-related services. You can list your services for hire on this site. There's a section of the site dedicated to music job postings.

Landing a composing gig is hard if you approach it through traditional job search methods. Composing gigs are rarely advertised to the public. If you're looking for job postings to send your resume, you're probably going to have a hard time. Most composing gigs come from established networks. They come from people who already know you and your work. You need to go and establish relationships with people who are actively creating music-related projects long before they need music.

The good news is that once you've landed one gig, the client will often use your services time and time again, and it'll be much easier to find referrals for further projects.

Preparing for meeting clients

What you'll soon discover going into interviews with clients is they often don't know what they're looking for in a soundtrack. Sometimes, the client thinks they know what they want, but they aren't musicians themselves and often have no idea how to make music. They might know what they like and have a vision of what it might sound like, but that's like pointing at a piece of art and saying, I want something just like that…but also tailored toward my preferences. Very vague. You're getting hired by someone who doesn't know how to do the job themselves...and they're super picky about the work delivered.

Landing a composing job with a client requires the ability to translate the client's vision into musical ideas and explain it to the client without using music terminology. To get hired, you need to demonstrate you have the skills to do this when you're pitching yourself for a client's project. It's your job to figure out what the client wants and to guide them along the way if they aren't sure. If the client claims they know what kind of music they want, it's your job to get it out of them and articulate it to all parties.

The person who can best figure out what the client wants and explain it clearly back to them is a likely candidate to get the job. This is also the reason that directors usually rely on composers they've worked with before—they know they can trust their composer to deliver an idea that meets their vision. So, the conversation with the client is a lot about building trust and rapport. In order to get them to trust you, you have to show them that you're genuinely curious and interested in their project.

Don't play hard to get at this stage. It's too early on to think about money. In fact, I recommend not bringing up the topic of money until the client has already decided that they want you for the project. You want to get as many details as you can, show that you're capable, and have a plan of attack as to how you'll add value to the film. If you simply list off a price before the client sees the value you bring, then you might put yourself into a bidding war for the lowest price with other composers.

The price you can charge a client depends on the following factors:

- The client's budget.

- The size of the project (for example, number of songs/length required).

- Your track record. If you have a strong portfolio or reputation, it's easier to charge more.

- Expenses that are required to create a score (for example, hiring musicians, recording sessions, and equipment rentals).

- The value your music adds to the project.

You might ask, How much is this value? Well, art is subjective, and the value that music adds to any project is assessed differently every time It's up to you to convince the client your music has value. Lots of value. Yes—you might put a number of hours into a project and arbitrarily assign an hourly rate, but how much to price those work hours is up to negotiation. Whatever amount you can convince the client of, you can charge.

A lot of composing gigs are freelance contracts. As a general rule of thumb, as a freelance contractor, it's smarter to charge a high price per hour. For example, let's say the client has a budget of $500 (US dollars). You might say, I'll charge $50/hour for 10 hours to get the job done, rather than saying you need $10/hour for 50 hours. You get $500 either way, but in the first approach, if something happens and the client needs more music, the client will respect your time a lot more than they will in the second scenario. In order to charge a higher price, you need to come across as a professional. The more capable and professional you come across, the more reasonable your price will seem to the client.

We've discussed landing a job with a client. Next, let's discuss what to do once you've got the gig.

Planning a music score

Getting the planning right for a music score is a crucial part of the job. The more prepared and detailed your plan, the easier it will be to do the job. Careful planning acts as a safeguard checklist to ensure you correctly gathered all the requirements needed and didn't forget anything. The first part of planning a music score is gathering client requirements in a document that we'll refer to as the music design document.

During your interviews with clients, you'll want to write down as much detail as you can in this document. There are a number of key items you will want to consider putting in the document. What follows are some suggestions.

Composing for films

For film music, you'll break down each scene into significant events to determine what kinds of sounds are required. Here are some items you'll want to account for:

- What emotion/tone/mood does the director want?

- What's the intensity of the scene?

- Is there dialogue in the scene?

- What Foley sounds are present (sounds that are part of the actual scene)?

List out the ideas you have and what you have in mind for the client. If you need specific instruments, equipment, session musicians, and so on, you can list your requirements here. You can use the music design document as a sort of proposal to get approval if you need to ask for a music budget later.

Composing for video games

For video games, the composer is usually brought into the development phase much earlier than in films. You will likely only have concept art to work on to get an idea of what the game could look like. The music can help to set the emotional tone and may influence other design aspects of the game, so your music may have a large influence on the design of the game itself. Many games incorporate music as part of the gameplay.

Video games have a variety of events that require music, and these requirements need to be gathered and itemized in the planning stage. Examples of situations requiring music in games include the following:

- Menus

- Loading level screens

- Entering new levels

- Completing levels

- Music for each boss

- Entering new rooms

- Obtaining items

- Unlocking achievements

- Ambient sounds for environments

- Battle sounds

- Cutscenes

- Music that characters are listening to within the game

- Winning the game

- Losing the game

The nature of your involvement may vary depending on the type of game. Most video games have a variety of cutscenes that require music. You can treat these cutscenes as you would any film score.

For some video games, you may be involved in more of the development of the game. You may have to design interactive music that changes throughout the game. If composing interactive music, you'll need a much more comprehensive music design document. The document will need to keep track of how music changes throughout the levels. If there are layers of music that are played on top of each other, the design document could specify conditions where these music layers are added. You will want to keep this document maintained and up to date each time you complete a piece of music for the project.

We discuss music for video games in more detail in Chapter 7, Creating Interactive Music for Video Games with Wwise.

Gathering soundtrack requirements for the design document

For film projects, composers are usually brought in after filming has commenced or been completed and is in the postproduction stage. This usually means there is a rough cut of gathering for the design document. It may be missing audio, but there are some visuals for you to get an idea of what the film will look like. This makes everything significantly easier because you can see how pieces fit together, how long each song should be, and the key moments the music needs to hit.

If the client provided you with a rough cut of the video, they'll usually give you suggested timings for when music could be played. For video games, there will usually be an itemized list you or the client will create for each thing/level/environment requiring sound.

Temp music is music that has been temporarily placed in a film or game to give the viewer an idea of what the music could sound like. It's usually music that was composed for other films or video games that the client likes. Composers have a conflicting view of temp music. On one hand, it gives an idea of what the director has in mind. On the other hand, it could cause you or the director to get so attached to the temp music that you try to compose music mimicking it. This is a trap that's easy to fall into. Trying to recreate a great piece of music used in another film is not a task you want to be doing. If the temp music is perfect, then they don't need you to compose anything else. You may as well just use the temp music. You want to be inspired by the temp music, and then go out and create something original.

Consider how the temp music adds value to the film and where it's lacking. Don't accept the temp music as a requirement for the project at face value—it's just a placeholder. You should ask the director why they chose each temp track and figure out what their intention was for the chosen piece. It could be that the director wants a certain emotion or intensity, but you won't know for sure unless you ask.

There's a quote sometimes attributed to Pablo Picasso: Good artists borrow, great artists steal. Let's discuss how to "steal" ideas in the right way. Listening to temp music and copying is, of course, bad practice. However, if you take ideas from multiple songs and combine them in a new way, you're no longer stealing—now, you're being inspired. Take the idea that you want to copy, then find a few more ideas that you want to copy, and finally, create a hybrid of the bunch.

Watching the film with the client

Arrange a time to sit down with the client and watch the film together, stopping at moments where music should come in. Discuss the emotional tone that should be delivered by the music at key moments in the film. When I do this, as we're watching, I'll have my laptop out and will furiously type down notes, timings for the film, desired emotions, and any comments that come up in conversation.

Most of the time, in client conversations, you'll explain music using examples as a reference—references such as other famous movies and descriptions of iconic scenes. You'll probably never discuss music theory with the client. More likely, you'll discuss how a scene makes the client feel. What is it about the scene that makes them feel that way?

If the director provided temp music, I'll go through and write the timings for each temp music track. Any notes and thoughts that come to mind while watching the footage I'll record down.

After the meeting, I'll collect the notes, organize the thoughts in a logical manner, and rewrite them into the design document.

Once the design document is done and approved, it's then time to create a document I like to call the Soundtrack Planner. This document will schedule the entire music score for the project. It will take all the requirements that we identified in the design document and itemize everything into actionable pieces. The Soundtrack Planner document will also serve to be the communication tool to help all parties plan the music score.

Creating a Soundtrack Planner

How do you organize a film score? If it were a single song, you might not need much planning. But we're not talking about a single song. We're talking about dozens, potentially hundreds of different pieces of sound. If you're working on a video game soundtrack, you might need to keep track of programming consideration details as well.

When you get feedback from the client for your music, it's not as simple as just asking an opinion. You'll get an answer, but it might not be something you know how to act upon. You need to have a logical method to keep track of all suggestions and changes and formulate them into actionable steps you can carry out.

If you're looking at a big-budget film, the company may have some sort of ticket-tracking software they want to use. More often, though, the client leaves you in charge of organizing your own score.

I personally find that a good old Google Drive document or SharePoint shared document is simple and does the job. Most people already know how to use shared drive documents, so you don't have to worry about the client not knowing how to use the software.

You can share a link to the editable document with the director and crew. Everyone has access to the same document, so everyone can always see the latest version. Make sure you keep a backup copy of the document at regular intervals just in case someone comes in and accidentally messes everything up.

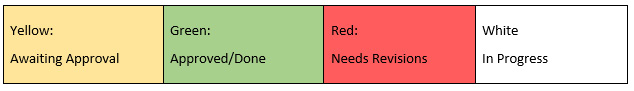

Here's an example of a Soundtrack Planner that I used for a client. I included a Time column showing the suggested location to place the music in the film, a column with the filename of the song, a column for a description of the song requirements, a column for the song status, and columns for comments from the client and composer:

Figure 1.5 – Soundtrack planner

In the document, I include a legend that's color-coded to make it easy for the director to understand the status each song is currently in. For example, I use white for In Progress, yellow for Awaiting Approval, green for Approved/Done, and red for Needs Revisions, as illustrated here:

Figure 1.6 – Soundtrack planner legend

If the director were to quickly glance at this table, they would be able to get an idea of the status for each song in the project. Whenever I make progress on the songs, I'll update the shared drive with the songs and update the document with the relevant information. Then, I'll send a link with the shared document to the director to let them know some changes were made.

If you don't use an organized method for your score, it's very easy to lose track of what work has already been done. Make sure you name your filenames in an easy-to-understand method. I like to include the song name and a suggested timing for the song in the film. For example, I might call a song 00.46.00 – Boss Fight – Version 3.

This title lets the director know where to place the music timewise in the film, what the scene is about, and the current song version so that they can make sure they're using the latest version. You might also want to consider including the song tempo and song key in the name.

You want to make it as little work as possible for the director to use your music. If the director is losing track of where your music is, unsure which song goes where in the film, what the status of a song's progress is, or which version of a song they should be using, this means your music could be organized more effectively.

If you do your job right, the director should be able to open the Soundtrack Planner and instantly know what work has been done. They can then open a folder containing your music and easily navigate through the folder structure to find your song. The song should be labeled in such a way that the director knows exactly what it is and how to use it based on the comments in the Soundtrack Planner.

I've received positive feedback from directors in the past saying they really liked this Soundtrack Planner method of organizing music. They said they found it clear and easy to use and that it helped them know how the project is coming along and how much more work needs to be done.

Researching music ideas for the project

Once you've got the outline for your Soundtrack Planner, the fun part now begins: the research for musical ideas. You have your soundtrack requirements; now, you need to go out into the field and get inspired. It's time to create an inspiration board of resources to draw from.

I usually look up music in movies or games that were discussed with the client during conversations. I'll review the temp music used. I'll pay special attention to the instruments. I'll note the style and see whether I can dig up information on which tools and software techniques were used. The goal isn't to recreate the sounds but to get ideas about what has been done before so you have the information to hand if you need it later.

Clips from films and games can always be found online on YouTube. I'll create a document filled with links and descriptions of relevant clips. If I need inspiration for a scene, I can use this document for reference.

If I have time, I may spend effort curating original sounds and instruments. Some composers go around recording sounds on their phones. They can then use the sounds as audio samples and manipulate the samples into whatever they need.

I personally like to search for new genres of music that I normally wouldn't listen to—sounds that pull me out of my comfort zone often give me ideas for composing. When I'm not composing, I'm usually listening to electronic dance music. But when I'm composing for clients, I'll go on adventures seeking out unusual blends of sounds I'd normally never listen to. The weirder, the better. If it's a style of music I've never heard before, that really piques my attention.

At some point, you're going to run into writer's block. At these times, it's imperative you have something to turn to so that you can get your ideas flowing again. Having done your research beforehand and having a reference document on hand will help get the creative juices flowing when you need it. We'll cover many more tips for coming up with ideas for music composing in Chapter 3, Designing Music with Themes, Leitmotifs, and Scales, and we'll learn how to overcome writer's block in Chapter 8, Soundtrack Composing Templates.

In this section, we learned how to plan a film score. We also learned a method for researching your project. We learned how to organize your score using a Soundtrack Planner to help you and your client keep track of your music.

Next, let's learn how to collaborate on group projects with additional composers. This next tip is slightly more advanced and will likely be more relevant when you work on larger projects rather than when you're first starting out.

Collaborating with others

Sharing your music with collaborators requires organization and planning. If you're prepared, sharing your projects and music can be a relatively easy experience.

Make sure your music is in a format easily understood by your team members. You'll have to come up with an agreed-upon folder structure of files and formats. Talk about this beforehand to make sure that everyone understands how to locate the music.

Make it easy for collaborators to know what your music is just by reading the file- and folder-naming structure. Consider labeling folders with information such as the following:

- Filenames and formats

- The genre of the music

- The tempo and song key

- Instrumentation

Problems with collaborating

When collaborating with other composers, you'll soon encounter the difficulties of trying to share project files and keeping track of the latest file. If someone else needs to access your music project file and they don't have access to your computer, what can they do?

First, think about what happens if you send the entire project file to someone else. If they try to open up the project and don't have the same digital audio workstation as you, they won't be able to open it directly as their project files will be incompatible.

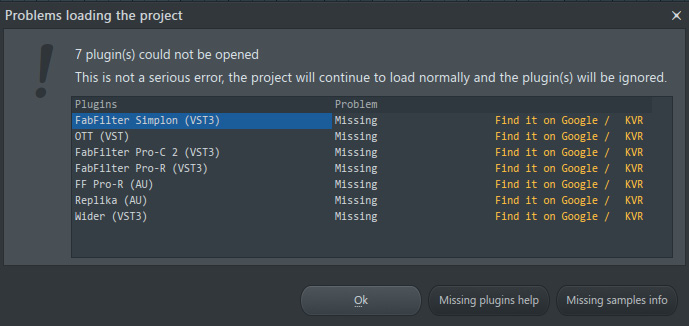

If they do have the same digital audio workstation as you but don't have the same instrument plugins installed, they'll be able to open the project but still won't be able to use it because plugins will be missing. This will result in an annoying error screen, such as the following:

Figure 1.7 – Opening projects with missing plugins

Trying to navigate missing plugins is a nightmare. You have to figure out what plugins are missing. Then you have to try to recreate the settings used. Not fun!

These problems come up all the time if you don't communicate in advance. This is easy to overlook if you haven't collaborated with another musician before, but it can cause you many hours of frustration and is easy to avoid. To avoid all of this, make sure you figure out and agree upon which digital audio workstation and plugins you and your collaborators will have access to before you begin. Make sure you only use plugins that all parties have access to.

Version control with Splice

What if you and your collaborators are using different digital audio workstations? This means you won't be able to send the entire project file, since the collaborators won't be able to open it. If that's the case, you're going to need to plan to export audio stems from your project each time you want to send music to someone else.

If you are both using the same digital audio workstation, then collaborating is much easier. But you'll still need to figure out which instrument and effect plugins you both have access to. Then, you'll need to have a discussion about how to update each other on changes when you make them—for example, send each other a message each time you make changes to your music project to let the other know there's a new project version.

Have I lost you yet? If this sounds confusing, it's because it is. Trying to figure out the latest version of a project file is tedious and messy. Fortunately, there is a solution: version control software. Software developers figured out that there needed to be a way to manage file versions long before musicians did. Using version control software such as Git is now mandatory for most programmers.

In recent years, version control software has emerged for musicians too. One of the most popular music version control software solutions is called Splice. It allows you to save your project at different stages in a remote repository and open up previous versions of your project. Most importantly, you can share your Splice project file with collaborators so that they have access to the latest project version at all times.

Note

You can download Splice for free at https://splice.com.

Once in Splice, you can share the project file with your collaborators' Splice accounts, and they'll gain access to all the versions of the project file. The following screenshot shows the Splice home page:

Figure 1.8 – Splice site

At the time of writing, Splice doesn't have the ability to merge changes between file versions like Git does, so only one of you will be able to make changes at a time to the newest project version. You won't be able to make changes simultaneously. This means that each time you plan to work on the project file, it's essential that you log in to Splice and open up the most recent version of the project. If you don't do this, you'll probably find yourself working on an outdated version of the project file.

Splice also offers a library of royalty-free sounds that you can pay for and use in your projects. It also allows you to rent instrument plugins until you've paid off the amount that it would take to originally buy the plugin and lets you own it afterward. So, if you're strapped for cash at the moment but need plugin equipment, this may be a handy alternative to buying instrument plugins outright.

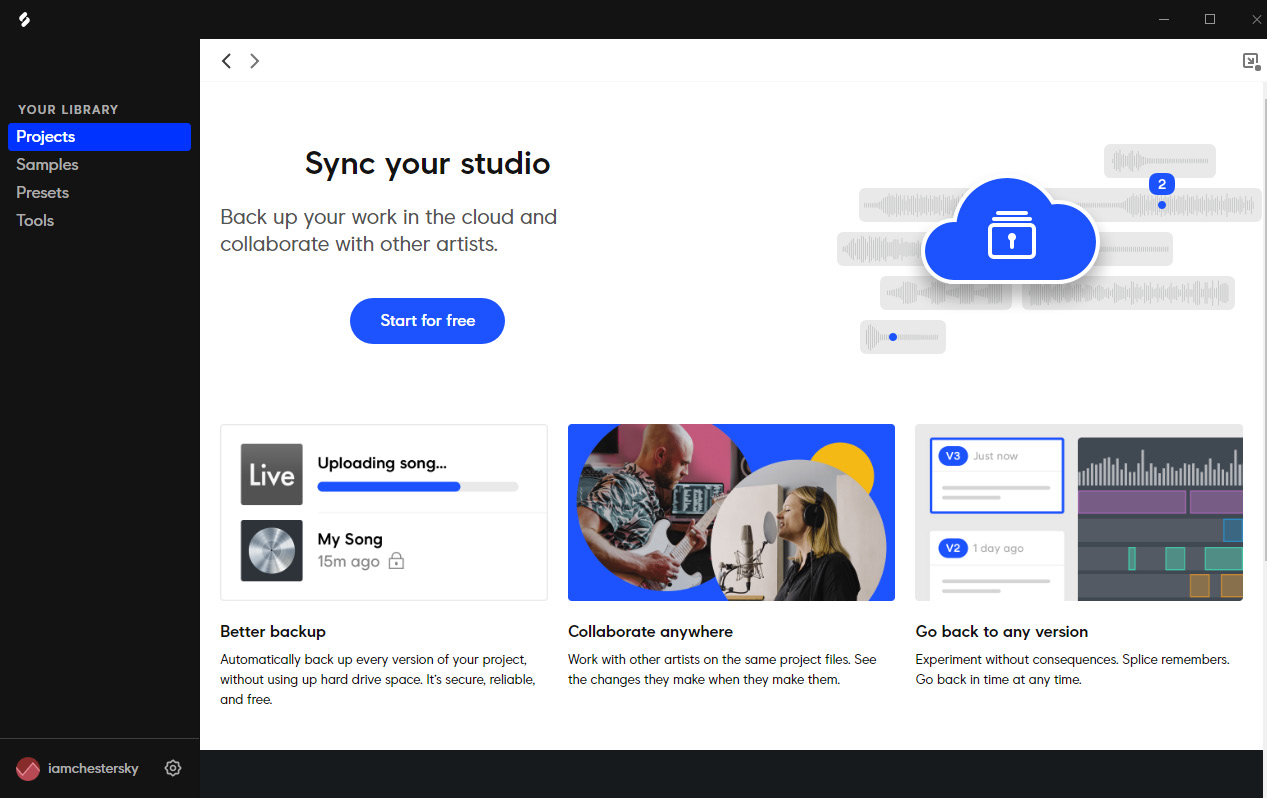

When you log in to Splice, you'll see a screen similar to this:

Figure 1.9 – Splice dashboard

On the left-side panel, you'll see the ability to navigate to your project, download samples, or see tools available in Splice.

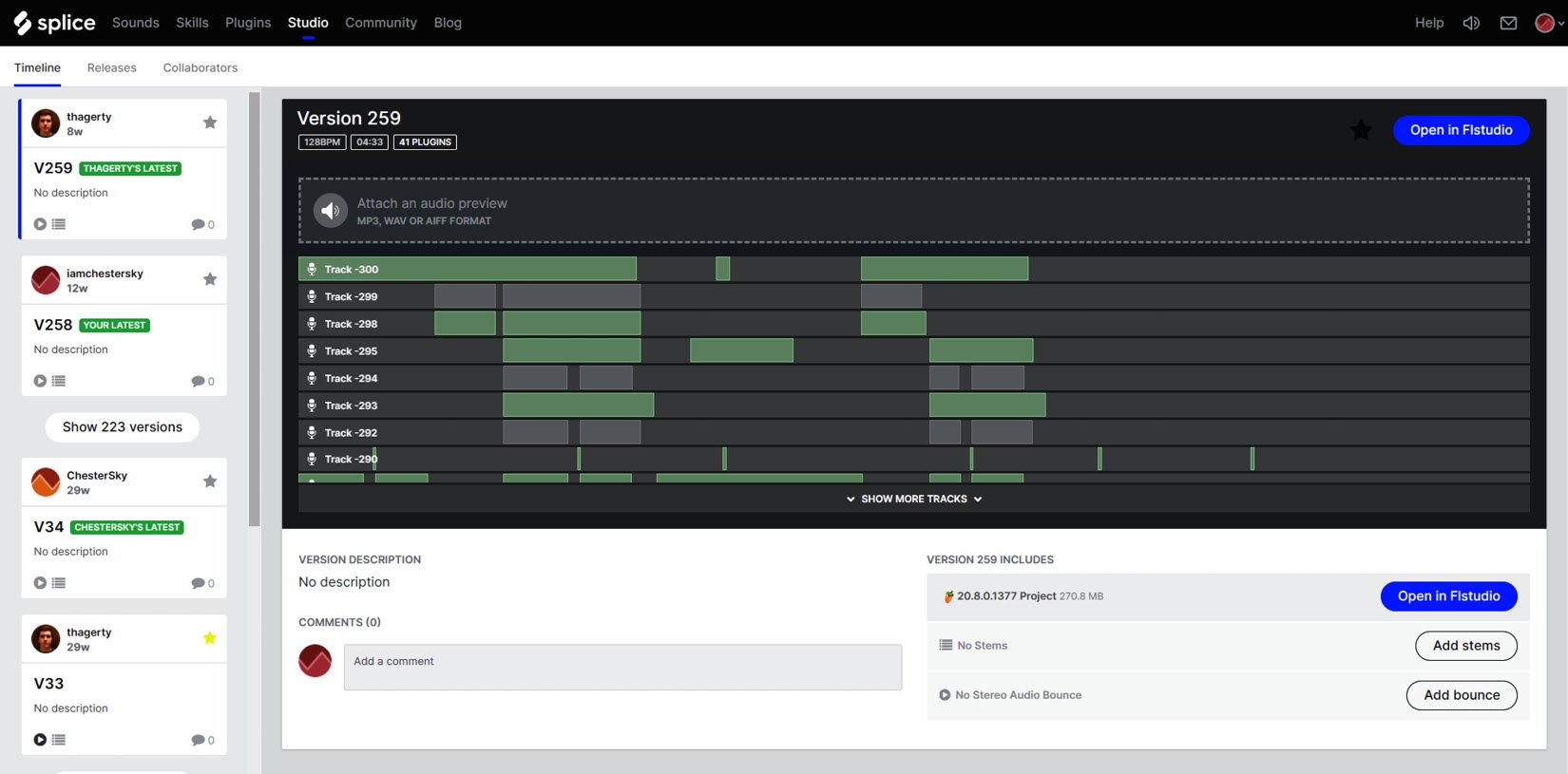

Each time you save your project, Splice will add a new version to the repository. You can add comments to individual tracks for collaborators to see. If you are using the same digital audio workstation, you can open up the project file from Splice and it will automatically keep your project files in sync going forward. The following screenshot shows an example of Splice Studio, which allows you to manage song versions:

Figure 1.10 – Splice versions

In the preceding screenshot, you can see an example of how Splice displays your project for collaboration. On the left side, it lists previous versions of the project that you can choose to open. The top middle shows any changes made, and the bottom lets you enter any notes and comments you wish to record.

Using Splice to collaborate with team members can work great if you have solid communication. If you don't have good communication, then you're going to run into problems. Problems come when you start working on a song version that isn't the latest.

Each time you work on a new song version, you need to notify your team members that you are saving a new version. This way, they can remember to open up the new version before making modifications. As long as you're all taking turns working on the latest version, you'll be able to avoid problems.

We've discussed how to share music with collaborators. Next, let's learn some tips for newbies.

Advice for avoiding rookie mistakes

What follows are a few items you might overlook if you're new to composing music.

Get the project in writing

You should have some sort of documentation stating the services you plan on providing for the client before you begin work. This sounds obvious, but when you're starting out, the client may not have a contract drafted up ready for you. If you don't have any documentation to say you have the job, you should assume you don't officially have the job.

The client could easily swap you out with another composer at any moment's notice, and there wouldn't be much you could do about it. If the client doesn't have a contract for you, it's not a problem. Just draft up an invoice and send it to them confirming the fees for your project to seal the deal. Agreeing to something in writing psychologically makes people feel like they're serious about the agreement. It also allows all parties to know what the expectations are of each other to help avoid confusion.

If you're drafting up an invoice, include the following details:

- Contact information of you/your company

- Contact information of the client

- Services you're providing for the client

- Dates for services and/or deadlines

- Itemized pricing for the services or hourly rate, depending on how you want to bill the client

By the time you're drafting up the invoice, you've probably discussed the budget for the project already. The invoice is usually just confirming whatever you already agreed to earlier on. However, if you haven't officially agreed on a price yet, an invoice is a way to make the first offer while at the same time providing reasons to back up why you are charging your prices. You could, for example, list out songs that need creating and assign an expected number of budgeted hours for each.

The nice thing about drafting up your own invoice is you can put on it whatever you want. It's then up to the other party to disagree and request adjustments, but oddly enough, clients rarely do. Usually, whatever you put into an invoice ends up staying.

I've even used invoices to intentionally get myself out of composing gigs I didn't want. One time, a client came to me with an uninteresting assignment that would have been a huge commitment that I didn't have time to do at that moment. Saying no to someone offering a music job is something I always want to avoid. It might burn a bridge with them, and who knows who they are connected with. Instead of saying no, I simply listed out the services as usual on my invoice and itemized each with a very high price that was still justifiable, but unlikely that the client would be willing to pay. It was a way for me to back out of the deal while saving face.

Ask for feedback

One of the biggest mistakes you can run into when composing is not getting enough feedback. Now, this may sound like common sense, but it's not. The way you obtain feedback and adapt is a delicate balancing act. This is a fragile part of the job. If you do it wrong, you'll annoy the people you ask and look like you don't know what you're doing, and no matter how good your music is, you'll create a bad impression. Do it right, and you'll establish trust with the client and be brought back again and again to do more jobs.

Most of the time when playing music, your audience isn't scrutinizing every detail of your song and telling you what they think. Even if you get feedback when playing for a live audience, they probably don't have a specific critique that is easily actionable.

This is not the case when composing for clients. Working with a client is a completely different environment where feedback is everything. If your client says nothing when you hand them music, that doesn't mean they love the music. It means that the client isn't thinking about the music. That's a big distinction.

I made this mistake on my first composing gig. On my very first movie, I composed a soundtrack for the whole film. It took a few months of work. The client said nothing when I sent him the music throughout, and I thought that meant he must like the music. Why would someone hire you for a job and say nothing when you send them the work? It turned out it was because his attention was focused on other things. When I told the client I was done, he said he hadn't listened to any of the music yet. When he put the music in the film, he said he didn't like what he heard. He wanted me to redo the whole thing.

He thought that it was my fault. With some time and distance from the event, when I look back on it, he's right. It's the composer's job to put in the effort to make sure their music is received. Don't let my mistake happen to you. As often as you can, check in with the client and ask for feedback constantly. If they haven't said anything about your music for a while, always assume that they haven't reviewed the music yet and that you need to follow up.

It was because of this experience that I was forced to look into a better approach for planning out my soundtrack scores. After experimenting, I settled upon the Soundtrack Planner method discussed earlier in this chapter. If you keep updating the Soundtrack Planner and notifying the client about your changes, you should be able to collect feedback effectively and guarantee effective communication.

We've discussed advice for rookies. Next, let's discuss what an average day might look like on the job.

The day-to-day tasks of composing

Here's what a typical day might look like when composing. First, I'll check my Soundtrack Planner to see what items need to be completed and what priority they have. I'll also check my design document to see any notes regarding the music.

If I don't already have an idea of what music to make, I'll spend some time reviewing my previous research reference documents. I might have some instruments I want to use, references that inspire me, or a visual to get me in the right frame of mind.

If it's a film or game cutscene, I'll set markers for the video footage in my digital audio workstation. I'll put labels onto key moments to visually keep track of events the music needs to hit. We'll cover this in detail in Chapter 5, Creating Sheet Music with MuseScore, Scoring with Fruity Video Player, and Diegetic Music. I like to have a separate project file for each scene, although I will duplicate project files and reuse the instruments and effects loaded.

Next, I need a sound I think will work for the scene. This is where the fun and experimentation begin. I'm a piano guy, so I usually start with finding chords. I'll try to figure out a chord progression that gives me the tone I want for the scene. This takes me a while, and I'll go through several iterations because I feel strongly that chord progressions are the foundation of whether a song sounds good in the end or not. Some composers aren't as picky about the chords early on and prefer to identify a specific sound that fits the scene. There are many ways to start and there are many right answers. We'll cover lots of suggestions for coming up with musical ideas in Chapter 3, Designing Music with Themes, Leitmotifs, and Scales.

Once I'm happy with my chord progression, I'll begin identifying instrumentation for the song. I'll assign melodies in my chord progression to different instruments. I'll layer on instruments. I'll play around with breaking up chords to add some rhythm. I'll tweak the arrangement to hit the various timing marks. By the end, ideally, I'll have several variations of each song.

Composing and arranging the song is the first part. Afterward you need to think about mixing and mastering the song. Sometimes, I want to send an unmixed piece to the client first to get feedback before pouring more hours into something they potentially may not like.

For mixing, I'll segment the instruments into different mix busses based on the frequency range. I'll then apply equalization and compression to isolate/enhance the instruments. I'll try to make instrument frequencies not compete with each other. I may add effects, such as reverb. I'll balance out the volume levels for the instruments.

If you want to learn the ins and outs of mixing with FL Studio, check out my book The Music Producer's Ultimate Guide to FL Studio 20:

https://www.amazon.ca/Music-Producers-Ultimate-Guide-Studio/dp/1800565321

Once I have some song drafts I'm happy with, I'll export the song and label and organize it so that the client can easily identify what it should be used for. I'll upload it to a shared drive folder. I'll make some notes in the Soundtrack Planner to update it with information about any new songs. Then, I may send a little message to the client, letting them know there's some new music to be reviewed.

At regular intervals, there will also be meetings or phone/video calls with the client to discuss the client's vision for the project and review music to collect feedback. With any feedback, I'll take notes in the music design document to use for reference moving forward.

We've learned about the daily tasks of composing; next, let's learn how to collect revenue from music royalties.

How to collect music royalties

Some client projects pay you through a fixed rate whereby you sign over all the rights for your music. When you're working on a low-budget independent film, you have significantly more negotiating power than when working with large studios. Sometimes (especially if they're hiring you for cheap), you can negotiate so that the client only gets the rights to use your music but you get to keep the ownership rights. This means you can reuse and profit off the music outside of the client's project.

If you can keep ownership rights, you can register your music to collect music royalties. That way, the music you create will generate additional revenue for you whenever someone plays it.

How revenue gets collected for music plays can be very complex. Different regions around the world have different organizations that collect revenue. Trying to keep track of when a song of yours was played on a radio station would be impossible to do yourself. Thankfully, you don't have to.

There are several organizations tasked with collecting revenue from music plays and allocating the music revenue back to creators. These organizations do take a small cut of the revenue, but you wouldn't be able to collect the money without them, so you don't really have a choice.

One kind of royalty to be collected is called reproduction royalties, also known as mechanical royalties. Whenever your song is placed in a digital file, such as for online music distribution, this is a reproduction, and you are owed royalties for the play.

To collect reproduction royalties in the United States (US), you would use a performing-rights organization, such as the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI), or the Society of European Stage Authors and Composers (SESAC). You can only join SESAC by invitation, though.

You'll pick one of these organizations and register each of your songs with them. The organization will then collect royalty revenue for you. If you're in a different country, you'll want to check the designated collection body for that region.

Information about ASCAP is available at https://www.ascap.com/. You can see their logo here:

Figure 1.11 – ASCAP

Information about BMI is available at https://www.bmi.com/. Their logo is shown here:

Figure 1.12 – BMI

There are also public performance royalties. Whenever a song is played on the radio, on television, in a theatre, or at a concert, this is a performance royalty. If you are in the US and you're a performing artist and/or own the master recordings, you'll use an organization called SoundExchange to collect royalties. This organization collects and distributes performance royalties to the owners of the rights. If you're in another country, there may be a different organization that you'll need to register with.

Information about SoundExchange is available at https://www.soundexchange.com/. Their logo is shown here:

Figure 1.13 – SoundExchange

What about online stores? There are lots of online stores and streaming platforms that can sell your music. Here's a list of some of them:

Spotify, Apple Music, iTunes, Instagram/Facebook, TikTok/Resso, YouTube Music, Amazon, Soundtrack by Twitch, Pandora, Deezer, Tidal, iHeartRadio, Claro Música, Boomplay, Anghami, KKBox, NetEase, Tencent, Triller, Yandex Music, MediaNet

To make it easier to upload your music to all platforms at once instead of one by one, you can use a digital distribution service. This allows you to manage your music from a central dashboard and for revenue for online streaming and purchasing to be collected on your behalf. You only need one, but they do offer slightly different prices and services, so you'll likely want to compare them.

Here are some examples of digital distribution services you could use:

- DistroKid (https://distrokid.com/)

- LANDR (https://www.landr.com/)

- CD Baby (https://cdbaby.com/)

- TuneCore (https://www.tunecore.com/)

- Ditto Music (https://www.dittomusic.com/)

- Loudr (https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/loudr)

- Record Union (https://www.recordunion.com/)

- ReverbNation (https://www.reverbnation.com/)

- Symphonic (https://symphonicdistribution.com/)

- iMusician (https://imusician.pro/en/)

Note:

If you choose to use DistroKid as your digital distribution provider service, the following link provides you with a discount on your first year: https://distrokid.com/vip/seven/701180.

If you can, try to negotiate to keep the rights to your songs. Collecting royalties on your music is an additional source of revenue available to composers.

Summary

In this chapter, we learned about the business of composing music for clients. We learned about how to land a job creating music for clients to jumpstart your composing career. We discussed advice for how to come across as professional so that clients take you seriously, and we learned how to prepare for client meetings so that you use your client's time effectively. We learned how to plan out film scores so that you can schedule properly, how to collaborate with others when sharing project files, and how to use Splice for version control. Finally, we discussed how to collect royalties for your music.

In the next chapter, we'll learn how to use a digital audio workstation so that you can get started composing music.