Introduction to Multi-Cloud

Multi-cloud is a hot topic with companies. Most companies are already multi-cloud, sometimes even without realizing it. They have Software as a Service (SaaS) such as Office 365 from Microsoft and Salesforce, for instance, next to applications that they host in a public cloud such as Amazon Web Services (AWS) or Google Cloud Platform (GCP). It’s all part of the digital transformation that companies are going through, that is, creating business agility by adopting cloud services where companies develop a best-of-breed strategy: picking the right cloud service for specific business functions. The answer might be multi-cloud, rather than going for a single cloud provider.

The main goal of this chapter is to develop a foundational understanding of what multi-cloud is and why companies have a multi-cloud strategy. We will focus on the main public cloud platforms of Microsoft Azure, AWS, and GCP, next to the different on-premises variants of these platforms, such as Azure Stack, AWS Outposts, Google Anthos, and some emerging players.

The most important thing before starting the transformation to multi-cloud is gathering requirements, making sure a company is doing the right thing and making the right choices. Concepts such as The Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF) and Quality Function Deployment (QFD) will be discussed as tools to capture the voice of the customer (VOC). Lastly, you will learn that any transformation starts with people. The final section discusses the changes to the organization itself needed to execute the digital transformation.

In this chapter, we’re going to cover the following main topics:

- Understanding multi-cloud concepts

- Multi-cloud—more than just public and private

- Setting out a real strategy for multi-cloud

- Introducing the main players in the field

- Evaluating cloud service models

- Gathering requirements for multi-cloud

- Understanding the business challenges of multi-cloud

Understanding multi-cloud concepts

This book aims to take you on a journey along the different major cloud platforms and will try to answer one crucial question: if my organization deploys IT systems on various cloud platforms, how do I keep control? We want to avoid cases where costs in multi-cloud environments grow over our heads, where we don’t have a clear overview of who’s managing the systems, and, most importantly, where system sprawl introduces severe security risks. But before we start our deep-dive, we need to agree on a common understanding of multi-cloud and multi-cloud concepts.

There are multiple definitions of multi-cloud, but we’re using the one stated at https://www.techopedia.com/definition/33511/multi-cloud-strategy:

Multi-cloud refers to the use of two or more cloud computing systems at the same time. The deployment might use public clouds, private clouds, or some combination of the two. Multi-cloud deployments aim to offer redundancy in case of hardware/software failures and avoid vendor lock-in.

Let’s focus on some topics in that definition. First of all, we need to realize where most organizations come from: traditional datacenters with physical and virtual systems, hosting a variety of functions and business applications. If you want to call this legacy, that’s OK. But do realize that the cutting edge of today is the legacy of tomorrow. Hence, in this book, we will refer to “traditional” IT when we’re discussing the traditional systems, typically hosted in physical, privately owned datacenters. And with that, we’ve already introduced the first problem in the definition that we just gave for multi-cloud.

A lot of enterprises call their virtualized environments private clouds, whether these are hosted in external datacenters or in self-owned, on-premises datacenters. What they usually mean is that these environments host several business units that get billed for consumption on a centrally managed platform. You can have long debates on whether this is really using the cloud, but the fact is that there is a broad description that sort of fits the concept of private clouds.

Of course, when talking about the cloud, most of us will think of the major public cloud offerings that we have today: AWS, Microsoft Azure, and GCP. These are public clouds: providers that offer IT services on demand from centralized platforms using the public internet. They are centralized platforms that provide IT services such as compute, storage, and networking but distributed across datacenters around the globe. The cloud provider is responsible for managing these datacenters and, with that, the cloud. Companies “rent” the services, without the need to invest in datacenters themselves.

By another definition, multi-cloud is a best-of-breed solution from these different platforms, creating added value for the business in combination with this solution and/or service. So, using the cloud can mean either a combination of solutions and services in the public cloud or combined with private cloud solutions.

But the simple feature of combining solutions and services from different cloud providers and/or private clouds does not make up the multi-cloud concept alone. There’s more to it.

Maybe the best way to explain this is by using the analogy of the smartphone. Let’s assume you are buying a new phone. You take it out of the box and switch it on. Now, what can you do with that phone? First of all, if there’s no subscription with a telecom provider attached to the phone, you will discover that the functionality of the device is probably very limited. There will be no connection from the phone to the outside world, at least not on a mobile network. An option would be to connect it through a Wi-Fi device, if Wi-Fi is available. In short, one of the first actions, in order to actually use the phone, would be making sure that it has connectivity.

Now you have a brand-new smartphone set to its factory defaults and you have it connected to the outside world. Ready to go? Probably not. You probably want to have all sorts of services delivered to your phone, usually through the use of apps, delivered through online catalogs such as an app store. The apps themselves come from different providers and companies, including banks and retailers, and might even be coded in different languages. Yet, they will work on different phones with different versions of mobile operating systems such as iOS or Android.

You will also very likely want to configure these apps according to your personal needs and wishes. Lastly, you need to be able to access the data on your phone. All in all, the phone has turned into a landing platform for all sorts of personalized services and data.

The best part is that in principle, you, the user of the phone, don’t have to worry about updates. Every now and then the operating system will automatically be updated and most of the installed apps will still work perfectly. It might take a day or two for some apps to adapt to the new settings, but in the end, they will work. And the data that is stored on the phone or accessed via some cloud directory will also still be available. The whole ecosystem around that smartphone is designed in such a way that from the end user’s perspective, the technology is completely transparent:

Figure 1.1: Analogy of the smartphone—a true multi-cloud concept

Well, this mirrors the concept of the cloud, where the smartphone in our analogy is the actual integrated landing zone, where literally everything comes together, providing a seamless user experience.

How is this an analogy for multi-cloud? The first time we enter a portal for any public cloud, we will notice that there’s not much to see. We have a platform—the cloud itself—and we probably also have connectivity through the internet, so we can reach the portal. But we don’t want everyone to be able to see our applications and data on this platform, so we need to configure it for our specific usage. After we’ve done that, we can load our applications and the data on to the platform. Only authorized people can access those applications and that data. However, just like the user of a smartphone, a company might choose to have applications and data on other platforms. They will be able to connect to applications on a different platform.

The company might even decide to migrate applications to a different platform. Think of the possibility of having Facebook on both an iPhone and an Android phone; with just one Facebook account, the user will see the same data, even when the platforms—the phones—use different operating systems.

Multi-cloud—more than just public and private

There’s a difference between hybrid IT and multi-cloud, and there are different opinions on the definitions. One is that hybrid platforms are homogeneous and multi-cloud platforms are heterogeneous. Homogeneous here means that the cloud solutions belong to one stack, for instance, the Azure public cloud with Azure Stack on-premises. Heterogeneous, then, would mean combining Azure and AWS, for instance.

Key definitions are:

- Hybrid: Combines on-premises and cloud.

- Multi-cloud: Two or more cloud providers.

- Private: Resources dedicated to one company or user.

- Public: Resources are shared (note, this doesn’t mean anyone has access to your data. In the public cloud, we will have separate tenants, but these tenants will share resources, for instance, in networking).

For now, we will keep it very simple: a hybrid environment combines an on-premises stack—a private cloud—with a public cloud. It is a very common deployment model within enterprises and most consultancy firms have concluded that these hybrid deployments will be the most implemented future model of the cloud.

Two obvious reasons for hybrid—a mixture between the public and private clouds—are security and latency, besides the fact that a lot of companies already had on-premises environments before the cloud entered the market.

To start with security: this is all about sensitive data and privacy, especially concerning data that may not be hosted outside a country, or outside certain regional borders, such as the European Union (EU). Data may not be accessible in whatever way to—as an example—US-based companies, which in itself is already quite a challenge in the cloud domain. Regulations, laws, guidelines, and compliance rules often prevent companies from moving their data off-premises, even though public clouds offer frameworks and technologies to protect data at the very highest level. We will discuss this later on in Part 4 of this book in Chapters 13 to 18, where we talk about security, since security and data privacy are of the utmost importance in the cloud.

Latency is the second reason to keep systems on-premises. One example that probably everyone can relate to is that of print servers. Print servers in the public cloud might not be a good idea. The problem with print servers is the spooling process. The spooling software accepts the print jobs and controls the printer to which the print assignment has to be sent. It then schedules the order in which print jobs are actually sent to that printer. Although print spoolers have improved massively in recent years, it still takes some time to execute the process. Print servers in the public cloud might cause delays in that process. Fair enough: it can be done, and it will work if configured in the right way, in a cloud region close to the sending PC and receiving printer device, plus accessed through a proper connection.

You get the idea, in any case: there are functions and applications that are highly sensitive to latency. One more example: retail companies have warehouses where they store their goods. When items are purchased, the process of order picking starts. Items are labeled in a supply system so that the company can track how many of a specific item are still in stock, where the items originate from, and where they have to be sent. For this functionality, items have a barcode or QR code that can be scanned with RFID or the like. These systems have to be close to the production floor in the warehouse or—if you do host them in the cloud—accessible through really high-speed, dedicated connections on fast, responsive systems.

These are pretty simple and easy-to-understand examples, but the issue really comes to life if you start thinking about the medical systems used in operating theatres, or the systems controlling power plants. It is not that useful to have an all-public-cloud, cloud-first, or cloud-only strategy for quite a number of companies and institutions. That goes for hospitals, utility companies, and also for companies in less critical environments.

Yet, all of these companies discovered that the development of applications was way more agile in the public cloud. Usually, that’s where cloud adoption starts: with developers creating environments and apps in public clouds. It’s where hybrid IT is born: the use of private systems in private datacenters for critical production systems that host applications with sensitive data that need to be on-premises for latency reasons, while the public cloud is used to enable the fast, agile development of new applications. That’s where new cloud service models come into the picture. These models are explored in the next section.

The terms multi-cloud and hybrid get mixed up a lot and the truth is that a solution can be a mix. You can have, as an example, dedicated private hosts in Azure and AWS, hence running private servers in a public cloud. Or, run cloud services on a private host that sits in a private datacenter, for instance, with Azure Stack or AWS Outposts. That can lead to confusion. Still, when we discuss hybrid in this book, we refer to an on-premises environment combined with a public cloud. Multi-cloud is when we have two or more cloud providers.

Introducing the main players in the field

We have been talking about public and private clouds. Although it’s probably clear what we commonly understand by these terms, it’s still a good idea to have a very clear definition of both. We adhere to the definition as presented on the Microsoft website (https://azure.microsoft.com/en-us/resources/cloud-computing-dictionary/what-is-cloud-computing): the public cloud is defined as computing services offered by third-party providers over the public internet, making them available to anyone who wants to use or purchase them. The private cloud is defined as computing services offered either over the internet or a private internal network and only to select users instead of the general public. There are many more definitions, but these serve our purpose very well.

Public clouds

In the public cloud, the best-known providers are AWS, Microsoft Azure, GCP, Oracle Cloud Infrastructure, and Alibaba Cloud, next to a number of public clouds that have OpenStack as their technological foundation. An example of OpenStack is Rackspace. These are all public clouds that fit the definition that we just gave, but they also have some major differences.

AWS, Azure, and GCP all offer a wide variety of managed services to build environments, but they all differ very much in the way you apply the technology. In short: the concepts are more or less alike, but under the hood, these are completely different beasts. It’s exactly this that makes managing multi-cloud solutions complex.

In this book, we will mainly focus on the major players in the multi-cloud portfolio.

Private clouds

Most companies are planning to move, or are actually in the midst of moving, their workloads to the cloud. In general, they have a selected number of major platforms that they choose to host the workloads: Azure, AWS, GCP, and that’s about it. Fair enough, there are more platforms, but the three mentioned are the most dominant ones, and will continue to be throughout the forthcoming decades, if we look at analysts’ reports. Yet, we will also address Oracle Cloud Infrastructure (OCI) and Alibaba Cloud in this book when appropriate and when adding valuable extra information, since both clouds have gained quite some market growth over the recent years.

As we already found out in the previous paragraphs, in planning for and migrating workloads to these platforms, organizations also discover that it gets complex. Even more important, there are more and more regulations in terms of compliance, security, and privacy that force these companies to think twice before they bring our data onto these platforms. And it’s all about the data, in the end. It’s the most valuable asset in any company—next to people.

In the private cloud, VMware seems to be the dominant platform, next to environments that have Microsoft with Hyper-V technology as their basis. Yet, Microsoft is pushing customers more and more toward consumption in Azure, and where systems need to be kept on-premises, they have a broad portfolio available with Azure Stack and Azure Arc, which we will discuss in a bit more detail later in this chapter.

Especially in European governmental environments, OpenStack still seems to do very well, to avoid having data controlled or even viewed by non-European companies. However, the adoption and usage of OpenStack seem to be declining.

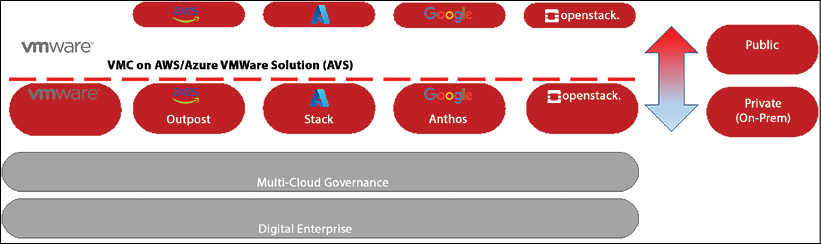

The following diagram provides an example of a multi-cloud stack, dividing private from public clouds.

Figure 1.2: An example multi-cloud portfolio: the main players

In this section, we will look briefly at both VMware and OpenStack as private stack foundations. After that, we’ll have a deeper look at AWS Outposts and Google Anthos. Basically, both propositions extend the public clouds of AWS and GCP into a privately owned datacenter. Next to this, we have to mention Azure Arc, which extends Azure to anywhere, either on-premises onto other clouds.

Outposts is an appliance that comes as a preconfigured rack with compute, storage, and network facilities. Anthos by Google is more a set of components that can be utilized to specifically host container platforms in on-premises environments using Google Kubernetes Engine (GKE). Finally, in this section, we will have a look at the Azure Stack portfolio.

VMware

In essence, VMware is still a virtualization technology. It started off with the virtualization of x86-based physical servers, enabling multiple virtual machines Virtual Machines (VMs) on one physical host. Later, VMware introduced the same concept to storage with virtualized SAN (vSAN) and network virtualization and security (NSX), which virtualizes the network, making it possible to adopt micro-segmentation in private clouds.

The company has been able to constantly find ways to move along with the shift to the cloud—as an example, by developing a proposition together with AWS where VMware private clouds can be seamlessly extended to the public cloud. The same applies to Azure: the joint offering is Azure VMware Solution (AVS).

VMware Cloud on AWS (VMConAWS) was a jointly developed proposition by AWS and VMware, but today Azure and VMware also supply migration services to migrate VMware workloads to Azure. VMware, acquired by Broadcom in 2022, has developed new services to stay relevant in the cloud. It has become a strong player in the field of containerization with the Tanzu portfolio, for instance. Over the last few years, the company has also strengthened its position in the security domain, again targeting the multi-cloud stack.

OpenStack

There absolutely are benefits to OpenStack. It’s a free and open-source software platform for cloud computing, mostly used as Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS). OpenStack uses KVM as its main hypervisor, although there are more hypervisors available for OpenStack. It was—and still is, with a group of companies and institutions—popular since it offers a stable, scalable solution while avoiding vendor lock-in on the major cloud and technology providers. Major integrators and system providers such as IBM and Fujitsu adopted OpenStack in their respective cloud platforms, Bluemix and K5 (K5 was decommissioned internationally in 2018).

However, although OpenStack is open source and can be completely tweaked and tuned to specific business needs, it is also complex, and companies find it cumbersome to manage. Most of these OpenStack platforms do not have the richness of solutions that, for example, Azure, AWS, and GCP offer to their clients. Over the last few years, OpenStack seems to have lost its foothold in the enterprise world, yet it still has a somewhat relevant position and certain aspects are therefore considered in this book.

AWS Outposts

Everything you run on the AWS public cloud, you can now run on an appliance, including Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2), Elastic Block Store (EBS), databases, and even Kubernetes clusters with Elastic Kubernetes Service (EKS). It all seamlessly integrates with the virtual private cloud (VPC) that you would have deployed in the public cloud, using the same APIs and controls. That is, in a nutshell, AWS Outposts: the AWS public cloud on-premises.

One question might be what this means for the VMConAWS proposition that both VMware and AWS have in their portfolio. VMConAWS actually extends the private cloud to the public cloud, based on HCX by VMware. VMware uses bare-metal instances in AWS to which it deploys vSphere, vSAN storage, and NSX for software-defined networking.

You can also use AWS services on top of the configuration of VMConAWS through integration with AWS. Outposts works exactly the other way around: bringing AWS to the private cloud. The portfolio for Outposts is growing rapidly. Customers can buy small appliances with single servers and also so-called rack solutions. In both cases, the infrastructure is completely managed by AWS.

Google Anthos

Anthos brings Google Cloud—or more accurately, GKE—to the on-premises datacenter, just as Azure Stack does for Azure and Outposts for AWS, but it focuses on the use of Kubernetes as a landing platform, moving and converting workloads directly into containers using GKE. It’s not a standalone box like Azure Stack or Outposts. The solution runs on top of virtualized machines using vSphere and is more of a Platform of a Service (PaaS) solution. Anthos really accelerates the transformation of applications to more cloud-native environments, using open-source technology including Istio for microservices and Knative for the scaling and deployment of cloud-native apps on Kubernetes.

More information on the specifics of Anthos can be found at https://cloud.google.com/anthos/gke/docs/on-prem/how-to/vsphere-requirements-basic.

Azure Stack

The Azure Stack portfolio contains Stack Hyperconverged Infrastructure (HCI), Stack Hub, and Stack Edge.

The most important feature of Azure Stack HCI is that it can run “disconnected” from Azure, running offline without internet connectivity. Stack HCI is delivered as a service, providing the latest security and feature updates.

To put it very simply: HCI works like the commonly known branch office server. Basically, HCI is a box that contains compute power, storage, and network connections. The box holds Hyper-V-based virtualized workloads that you can manage with Windows Admin Center. So, why would you want to run this as Azure Stack then? Well, Azure Stack HCI also has the option to connect to Azure services, such as Azure Site Recovery, Azure Backup, Microsoft Defender (formerly Azure Security Center), and Azure Monitor.

It’s a very simple solution that only requires Microsoft-validated hardware, the installation of the Azure Stack operating system plus Windows Admin Center, and optionally an Azure account to connect to specific Azure cloud services.

Pre-warning: it might get a bit complicated from this point onward. Azure Stack HCI is also the foundation of Azure Stack Hub. Yet, Hub is a different solution. Whereas you can run Stack HCI standalone, Hub as a solution is integrated with the Azure public cloud—and that’s really a different ballgame. It’s not possible to upgrade HCI to Hub.

Azure Stack Hub is an extension of Azure that brings the agility and innovation of cloud computing to your on-premises environment. Almost everything you can do in the public cloud of Microsoft, you could also deploy on Hub: from VMs to apps, all managed through the Azure portal or even PowerShell. It all really works like Azure, including things such as configuring and updating fault domains. Hub also supports having an availability set with a maximum of three fault domains to be consistent with Azure. This way, you can create high availability on Hub just as you would in Azure.

The perfect use case for Hub and the Azure public cloud would be to do development on the public cloud and move production to Hub, should apps or VMs need to be hosted on-premises for compliance reasons. The good news is that you can configure your pipeline in such a manner that development and testing can be executed on the public cloud and run deployment of the validated production systems, including the desired state configuration, on Hub. This will work fine since both entities of the Azure platform use the Azure resource providers in a consistent way.

There are a few things to be aware of, though. The compute resource provider will create its own VMs on Hub. In other words: it does not copy the VM from the public cloud to Hub. The same applies to network resources. Hub will create its own network features such as load balancers, vNets, and network security groups (NSGs). As for storage, Hub allows you to deploy all storage forms that you would have available on the Azure public cloud, such as blobs, queues, and tables. Obviously, we will discuss all of this in much more detail in this book, so don’t worry if a number of terms don’t sound familiar at this time.

One last Stack product is Stack Edge. Edge makes it easy to send data to Azure. But Edge does more: it runs containers to enable data analyses, perform queries, and filter data at edge locations. Therefore, Edge supports Azure VMs and Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS) clusters, which you can run containers on.

Edge, for that matter, is quite a sophisticated solution since it also integrates with Azure Machine Learning (AML). You can build and train machine learning models in Azure, run them in Azure Stack Edge, and send the datasets back to Azure. For this, the Edge solution is equipped with the Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) and Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) required to speed up building and (re)training the models.

Having said this, the obvious use case comes with the implementation of data analytics and machine learning where you don’t want raw data to be uploaded to the public cloud straight away.

Azure Arc

There’s one more service that needs to be discussed at this point and that’s Azure Arc, launched at Ignite 2019. Azure Arc allows you to manage and govern at scale the following resource types hosted outside of Azure: servers, Kubernetes clusters, and SQL Server instances. In addition, Azure Arc allows you to run Azure data services anywhere using Kubernetes as clusters for containers, use GitOps to deploy configuration across the Kubernetes clusters from Git repositories, and manage these non-Azure workloads as if they were fully deployed on Azure itself.

If you want to connect a machine to Arc, you need to install an agent on that machine. It will then get a resource ID and become part of a resource group in your Azure tenant. However, this won’t happen until you’ve configured some settings in the network, such as a proxy allowing for traffic from and to Arc-controlled servers, and registered the appropriate resource providers. The Microsoft.HybridCompute, Microsoft.GuestConfiguration, and Microsoft.HybridConnectivity resource providers must be registered on your subscription. This only has to be done once.

If you perform the actions successfully, then you can have non-Azure machines managed through Azure. In practice, this means that you perform many operational functions, just as you would with native Azure virtual machines. That sort of defines the use case: managing the non-Azure machines in line with the same policies as the Azure machines. These do not necessarily have to be on-premises. That’s likely the best part of Arc: Azure Arc-enabled servers let you manage Windows and Linux physical servers and virtual machines hosted outside of Azure, on your corporate network, or on another cloud provider (such as AWS or GCP, but not exclusively).

With that last remark on Arc, we’ve come to the core of the multi-cloud discussion, and that’s integration. All of the platforms that we’ve studied in this chapter have advantages, disadvantages, dependencies, and even specific use cases. Hence, we see enterprises experimenting with and deploying workloads in more than one cloud. That’s not just to avoid cloud vendor lock-in: it’s mainly because there’s not a “one size fits all” solution.

In short, it should be clear that it’s really not about cloud-first. It’s about getting cloud-fit, that is, getting the best out of an ever-increasing variety of cloud solutions. This book will hopefully help you to master working with a mix of these solutions.

Emerging players

Looking at the cloud market, it’s clear that it is dominated by a few major players, that is, the ones that were mentioned before: AWS, Microsoft Azure, and GCP. However, a number of players are emerging in both the public and private clouds, for a variety of reasons. The most common reason is geographical and that finds its cause in compliance rules. Some industries or companies in specific countries are not allowed to use, for instance, American cloud providers. Or the provider must have a local presence in a specific country.

From China, two major players have emerged to the rest of the world: Alibaba Cloud and Tencent. Both have been leading providers in China for many years, but are also globally available, but they focus on the Chinese market. Alibaba Cloud, especially, can certainly compete with the major American providers, offering a wide variety of services.

In Europe, a new initiative has recently started with Gaia-X, providing a pure European cloud, based in the EU. Gaia-X seems to concentrate mainly on the healthcare industry to allow European healthcare institutions to use a public cloud and still have privacy-sensitive patient data hosted within the EU.

Finally, big system integrators have stepped into the cloud market as well. A few have found niches in the market, such as IBM Cloud, which collaborates with Red Hat. Japanese technology provider Fujitsu did offer global cloud services with K5 for a while, offering a fully OpenStack public cloud, but found itself not being able to compete with Azure or AWS without enormous investments.

For specific use cases, a number of these clouds will offer good solutions, but the size and breadth of the services typically don’t match those of the major public providers.

Where appropriate, new players will be discussed in this book. In the next section, we will first study the various cloud service models.

Evaluating cloud service models

In the early days, the cloud was merely another datacenter that hosted a multitude of customers, sharing resources such as compute power, network, and storage. The cloud has evolved over the years, now offering a variety of service models. In this section, you will learn the fundamentals of these models.

IaaS

IaaS is likely still the best-known service model of the cloud. Typically, enterprises still start with IaaS when they initiate the migration to cloud providers. In practice, this means that enterprises perform a lift and shift of their (virtual) machines to resources that are hosted in the cloud. The cloud provider will manage only the infrastructure for the customer: network, storage, compute, and the virtualization layer. The latter is important, since customers will share physical resources in the cloud. These resources—for instance, servers—are virtualized so they can host multiple instances.

PaaS

With PaaS cloud providers take more responsibility over resources, now including operating systems and middleware. A good example is a database platform. Customers don’t need to take care of the database platform, but simply run a database instance on a database platform. The database software, for example, MySQL or PostgreSQL, is taken care of by the cloud provider, including the underlying operating systems.

SaaS

SaaS is generally perceived as the future model for cloud services. It basically means that the cloud provider manages everything in the software stack, from the infrastructure to the actual application with all its components, including data. Software updates, bug fixes, and infrastructure maintenance are all handled by the cloud provider. The user, who typically uses the application through some form of subscription, connects to the app through a portal or API without installing software on local machines.

FaaS

FaaS refers to a cloud service that enables the development and management of serverless computing applications. Serverless does not mean that there are no services involved, but developers can program services without having to worry about setting up and maintaining a server: that’s taken care of by the cloud provider. The big advantage is that the programmed service only uses the exact amount of, for instance, CPU and memory, instead of an entire virtual machine.

CaaS

A growing number of enterprises are adopting container technology to host, run, and scale their applications. To run containers, developers must set up a runtime environment for these containers. Typically, this is done with Kubernetes, which has developed as the industry standard to host, orchestrate, and run containers. Setting up Kubernetes clusters can be complex and time-consuming. Container as a Service (CaaS) is the solution. CaaS provides an easy way to set up container clusters.

XaaS

Anything as a Service (XaaS) is a term used to express the idea that users can have everything as a service. The concept is widely spread with, for instance, Hardware as a Service (HaaS), Desktop as a Service (DaaS), or Database as a Service (DBaaS). This is not limited to IT, though. The general idea is that companies will offer services and products in an as a service model, using the cloud as the digital enabler. Examples are food delivery to homes, ordering taxis, or consulting a doctor using apps.

Although we will touch upon SaaS and containers, we will focus mainly on IaaS and PaaS as starting points to adopt multi-cloud. With that in mind, we can start by setting out our multi-cloud strategy.

Setting out a real strategy for multi-cloud

A cloud strategy emerges from the business and the business goals. Business goals, for example, could include the following:

- Creating more brand awareness

- Releasing products to the market faster

- Improving profit margins

Business strategies often start with increasing revenue as a business goal. In all honesty: that should indeed be a goal; otherwise, you’ll be out of business before you know it. The strategy should focus on how to generate and increase revenue. We will explore more on this in Chapter 2, Business Acceleration Using a Multi-Cloud Strategy.

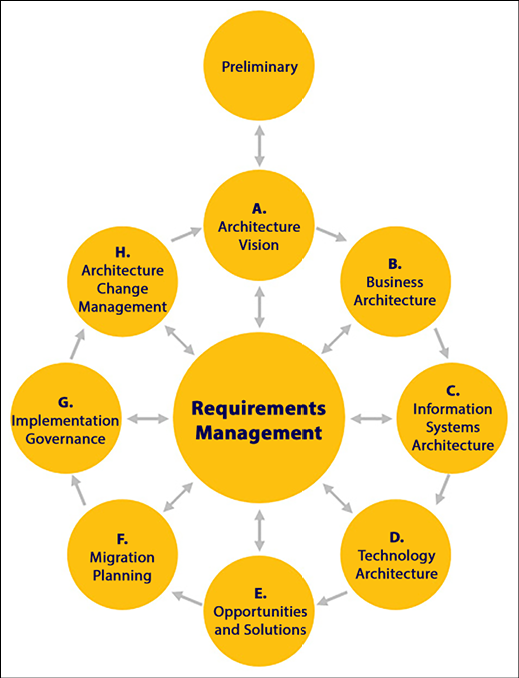

How do you get from business goals to defining an IT strategy? That is where enterprise architecture comes into play. The most used framework for enterprise architecture is TOGAF, although there are many more frameworks that can be used for this. Companies will not only work with TOGAF but also adopt practices from IT4IT and ITIL to manage their IT, as examples.

The core of TOGAF is the ADM cycle, short for Architecture Development Method. Also, in architecting multi-cloud environments, ADM is applicable. The ground principle of ADM is B-D-A-T: the cycle of business, data, applications, and technology. This perfectly matches the principle of multi-cloud, where the technology should be transparent. Businesses have to look at their needs, define what data is related to those needs, and how this data is processed in applications. This is translated into technological requirements and finally drives the choice of technology, integrated into the architecture vision as follows:

Figure 1.3: The ADM cycle in the TOGAF

This book is not about TOGAF, but it does make sense to have knowledge of enterprise architecture and, for that matter, TOGAF is the leading framework. TOGAF is published and maintained by The Open Group. More information can be found at https://www.opengroup.org/togaf.

The good news is that multi-cloud offers organizations flexibility and freedom of choice. That also brings a risk: lack of focus, along with the complexity of managing multi-cloud. Therefore, we need a strategy. Most companies adopt cloud and multi-cloud strategies since they are going through a process of transformation from a more-or-less traditional environment into a digital future. Is that relevant for all businesses? The answer is yes. In fact, more and more businesses are coming to the conclusion that IT is one of their core activities.

Times have changed over the last few years in that respect. At the end of the nineties and even at the beginning of the new millennium, a lot of companies outsourced their IT since it was not considered to be a core activity. That has changed dramatically over the last 10 years or so. Every company is a software company—a message that was rightfully quoted by Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, following an earlier statement by the father of software quality, Watts S. Humphrey, who already claimed at the beginning of the millennium that every business is a software business.

Both Humphrey and Nadella are right. Take banks as an example: they have transformed to become more and more like IT companies. They deal with a lot of data streams, execute data analytics, and develop apps for their clients. A single provider might not be able to deliver all of the required services, hence these companies look for multi-cloud, best-of-breed solutions to fulfill these requirements.

These best-of-breed solutions might contain traditional workloads with a classic server-application topology, but will more and more shift to the use of PaaS, SaaS, container, and serverless solutions in an architecture that is more focused on microservices and cloud-native options. This has to be considered when defining a multi-cloud strategy: a good strategy would not be “cloud first” but “cloud-fit,” meaning that a good strategy would not be about multi-cloud or single cloud, but having the right cloud.

Gathering requirements for multi-cloud

One of the first things that companies need to do is gather requirements before they start designing and building environments on cloud platforms. The most important question is probably: what will be the added value of using cloud technology to the business? Enterprises don’t move to the cloud because they can, but because cloud technology can provide them with benefits. Think about not only agility, speed, and flexibility in the development of new services and products but also financial aspects: paying only for resources that they actually use or because of automation being able to cut costs in operations.

Using TOGAF for requirements management

Design and build start with requirements. TOGAF provides good guidance for collecting business or enterprise requirements. As you have learned in the previous section, TOGAF starts with the business’ vision and mission. From there, an enterprise architect will define the business requirements, before diving into architectures that define the use of data, the need for specific applications, and lastly, the underlying technology. Indeed, technology comes in last. The architect will first have to determine what goals the business wants to achieve.

Requirements management is at the heart of the ADM of TOGAF. This means that from every phase of developing the architecture, requirements can be derived. Every requirement might have an impact on various stages of developing the architecture.

- TOGAF lists the following activities in gathering and managing requirements:

- Identify requirements

- Create a baseline for the requirements (the minimal set)

- From the baseline, identify changes to requirements

- Assess the impact of changes

- Create and maintain the requirements repository

- Implement requirements

- Perform gap analysis between the product specifications and requirements

This is all very generic. How would this translate to gathering and managing requirements for the cloud? The key is that at this stage, the technical requirements are not important yet. Architects shouldn’t bother about whether they want Azure Functions or Kubernetes in an AWS EKS cluster. That’s technology. It’s the business requirements that come first.

Business requirements for the cloud can be categorized into the following quality attributes:

- Interoperability

- Configurability

- Performance

- Discoverability

- Robustness

- Portability

- Usability

The number one business priority must be security. Businesses will host vital data in public clouds, so the cloud provider must provide security measures and tools to secure that data. All cloud providers do so, but be aware that cloud providers are only responsible for the cloud itself, not for what’s in the cloud. This shared responsibility model is crucial to understanding how public clouds work. Over the course of this book, you will learn much more about security.

Then, in general, there are three main goals that businesses want to achieve by using cloud technology:

- Scalability: XaaS and subscriptions are likely the future of any business. This comes with peaks in the demand for services and this means that platforms must be scalable, both upward and downward. This will allow businesses to have the right number of resources available at any time. Plus: since the cloud is very much based on OpEx, meaning that the business doesn’t have to invest upfront, you will pay for the usage only.

- Reliability: Unlike a proprietary, privately owned datacenter, public clouds are globally available, allowing businesses to have resources copied to multiple zones even in different parts of the world. If a datacenter or a service fails in one zone, it can be switched to another zone or region. Again: the provider will offer the possibilities, but it’s up to the business to make use of it. The business case will be important: is an application or data vital to a business and hence must be available at all times? In that case, business continuity and disaster recovery scenarios are valuable to work out in the cloud.

- Ease of use: Ease of administration might be a better word. Operators have access to all resources through comprehensive dashboards and powerful, largely automated tools to manage the resources in the cloud.

In multi-cloud, these requirements can be matched to services of various providers, resulting in solutions that provide the optimal mix for companies. With multi-cloud, other aspects will be evaluated, such as preventing technology lock-in and achieving business agility, where companies can respond fast to changing market circumstances or customer demands. The VOC will be an important driver to eventually choosing the right cloud and the right technology.

Listening to the Voice of the Customer

The problem with TOGAF is that it might look like the customer is a bit far away. TOGAF talks about enterprises, but enterprises exist thanks to customers. Customers literally drive the business, hence it’s crucial to capture the needs and requirements of the customers: the VOC. It’s part of an architectural methodology called QFD, which is discussed in more detail in the next section.

The challenge enterprises face in digital transformation is that it’s largely invisible to customers. Customers want a specific service delivered to them, and in modern society, it’s likely that they want it in a subscription format. Subscriptions are flexible by default: customers can subscribe, change subscriptions, suspend, stop, and reactivate them. This requires platforms and systems that can cope with this flexibility. Cloud technology is perfect for this.

However, the customer doesn’t see the cloud platform, but just the service they are subscribed to. Presumably, the customer also doesn’t care in what cloud the service is running. That’s up to the enterprise, and with the adoption of multi-cloud, the enterprise has a wide variety of choices to pick the right solution for a specific customer requirement. Customer requirements must then be mapped to the capabilities of multi-cloud, fulfilling the business requirements such as scalability, reliability, and ease of use.

This insight leads to the following question: how can enterprises expect customers to know what they want and how they want it? Moreover: are customers prepared to pay for new technology that is required to deliver a new service or product?

The VOC can be a great help here. It’s part of the House of Quality (HOQ) that is discussed in the next section. In essence, the VOC captures the “what”—the needs and wishes of the customer—and also prioritizes these. What is most important to the customer, that is, the must haves? Next, what are the “nice to haves”? These must be categorized into functional and non-functional requirements. Functional is everything that an app must be able to do, for instance, ordering a product. Non-functional is everything that enables an application to operate.

Think of the quality attributes: portability, reliability, performance, and indeed security. These are non-functional requirements, but they are just as important as the one button that allows customers to pay with a single click, integrating payment into an application with the credit card service. The latter is a functional requirement. It must all be prioritized in development since it’s rare that everything can be developed at once.

The Open Group has published a new methodology for enterprise architecture that focuses more on the needs of digital enterprises, embracing agile frameworks and DevOps. This method is called Open Agile Architecture (OAA). References can be found at https://www.opengroup.org/agilearchitecture.

In the next section, QFD and the HOQ are explained in more detail.

Defining architecture using QFD and the HOQ

The VOC has captured and prioritized the wants and needs of the customer: this is the input for the HOQ. The QFD process consists of four stages:

- Product definition: For this, the VOC is used.

- Product development: In the cloud, this refers to the development of the application and merging it with the cloud platform, including the development of infrastructure in the cloud.

- Process development: Although QFD was not designed specifically for cloud development, this can be easily applied to how development and deployment are done. Think of agile processes and DevOps, including pipelines.

- Process quality control: Again, QFD was not designed with the cloud in mind, but this can be applied to several test cycles that are required in cloud development. Think of quality assurance with compliance checks, security analysis, and various tests.

The HOQ shows the relations between the customer requirements and the product characteristics, defining how the customer needs can be translated into the product. The HOQ uses a relationship matrix to do this, listing how product characteristics map to the customer requirements. Every requirement must have a corresponding item in the product mapping. This is a design activity and must be performed on all levels of an application: on the application itself, the data, and every component that is needed to run the application. This includes the pipelines that organizations use to develop, test, and deploy applications in DevOps processes.

A good reference to get a better understanding of QFD is the website of Quality-One: https://quality-one.com/qfd/.

As with TOGAF, this book is not about QFD. QFD helps in supporting and improving design processes and with that, improving the overall architecture of business environments. Although ease of use is one of the business requirements of the cloud, it’s not a given that using cloud technology simplifies the architecture of that business. Cloud, and especially multi-cloud, can make things complex. A well-designed architecture process is a must, before we dive into the digital transformation itself.

Understanding the business challenges of multi-cloud

This might be a bit of a bold statement, but almost every modern enterprise has adopted multi-cloud already. They may offer Office 365 to their workers, have their customer base in the SaaS proposition of Salesforce, book trips through SAP Concur, manage their workforce in Workday, and run meetings through Zoom. It doesn’t get more multi-cloud than that. However, that’s not what enterprises mean by going multi-cloud.

It starts with a strategy, something that will be discussed in the next chapter. But before a company sets the strategy, it must be aware of the challenges it will encounter. These challenges are not technical in the first place, but more organizational: a company that plans for digital transformation must create a comprehensive roadmap that includes the organization of the transformation, the assessment of the present mode of operations, and the IT landscape, and next do a mapping of the IT services that are eligible for cloud transformation.

All of this must be included in a business case. In short: what is the best solution for a specific service? Can we move an application to the cloud as is, or is it a monolith that needs redesigning into microservices? What are the benefits of moving applications to the cloud? What about compliance, privacy, and security? A crucial point to consider is: how much effort will the transformation take and how do we organize it? By evaluating the services in various clouds and various solutions, businesses will be able to obtain an optimized solution that eventually fulfills the business requirements. In Chapter 2, Business Acceleration Using the Multi-Cloud Strategy, we will learn more about the business drivers for adopting multi-cloud.

In the next section, we will briefly address the organizational challenge before the start of the transformation. Chapter 2 talks about the business strategy, and Chapter 3, Starting the Multi-Cloud Journey, discusses the first steps of the actual transformation.

Setting the scene for cloud transformation

In this section, the first basic steps to start the cloud transformation are discussed. They may seem quite obvious, but a lot of companies try to skip some of these steps in order to gain speed—but all too often, skipping steps lead to failures, slowing down the transformation.

The first step is creating an accurate overview of the IT portfolio of the company: a catalog of all the applications and technology used, including the operational procedures. Simply listing that the company applies IT service management is not sufficient. What matters is how service management is applied. Think of incident, problem, change, and configuration management. Also, list the service levels to which services are delivered to the company, and thus to its business.

The following step is to map this catalog to a cloud catalog. The most important question is: what would be the benefit for the customers if services were transitioned to the cloud? To answer that question, the enterprise architect must address topics such as cloud affinity, various cloud service models, and the agreed Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) in terms of the business, security, costs, and technical debt of the company. It all adds up in a business case.

The company can now select the first candidates for cloud migration and start planning the actual migration. From that moment on, the cloud portfolio must be managed.

In Chapter 3, Starting the Multi-Cloud Journey, you will learn more about the transition and transformation of environments to the cloud, addressing topics such as microservices and cloud-native.

Addressing organizational challenges

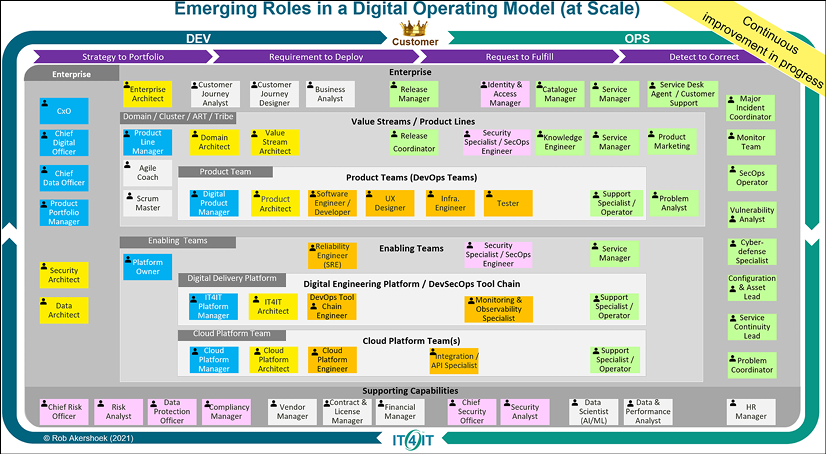

Digital and, as part of that, cloud transformation start with people. The Open Group released a digital operating model that shows how roles and skills are changing in a digital enterprise, using cloud technology. The model is continuously updated, reflecting the continuous change in transformation.

Figure 1.4: New roles in digital transformation (courtesy of Rob Akershoek)

The model shows a demarcation between enabling and product teams. The model assumes that there are more or less centralized teams that take care of the foundation, the landing zone, enabling the product teams to autonomously develop and deploy products.

Important new roles in the model are the customer journey analyst and the customer journey designer. The model places the VOC at the heart of everything.

Another important aspect of this model is the role of architecture. We can clearly see the hierarchy in architecture, starting with enterprise architecture setting the standards. The domain and value stream architects are key in translating the standards to the customer requirements, defining the architectures for the various products and releases. These architects are more business-focused. The IT and cloud platform architects are in the enabling layer of the model.

Organizing the skills of the architect

The role of an architect is changing, due to digital transformation. What is the current role of an architect do? It depends a bit on where the architect sits in the organization.

Let’s start at the top of the tower with the enterprise architect. First, what is enterprise architecture? The enterprise architect collects business requirements that support the overall business strategy and translates these into architecture that enables solution architects to develop solutions to deliver products and services. Requirements are key inputs for this and that’s the reason why requirements management sits in the middle of TOGAF, the commonly used framework for enterprise architecture.

In modern companies, enterprise architects also need to adapt to the new reality of agile DevOps and overall disruption through digital transformation. In TOGAF, technology is an enabler, something that simply supports the business architecture. That is changing. Technology might no longer be just an enabler, but actually drive the business strategy. With that, even the role of the enterprise architect is changing.

In fact, due to digital transformation, the role of every architect is changing. The architect is shifting toward more of an engineering leader, a servant leader in agile projects where teams work in a completely different fashion with agile trains, DevSecOps, and scrum, all led by product management. Indeed: you build it, you run it. That defines a different role for architecture. Architecture becomes more of a “floating” architecture, developing as the product development evolves and the builds are executed in an iterative way. There’s still architecture, but it’s more embedded into development. That comes with different skills.

The architect is shifting toward more of an engineering leader, that is, a servant leader. That’s true. The logical next question then would be: do we still need architects or do we need leading engineers in agile-driven projects? The answer is both yes and no and it’s only valid for digital architecture.

No, if architecture is seen as the massive upfront designs before a project can be started. Be aware: you will still need an architect to design a scanner. Or a house. A car. Something physical. The difference for an IT architect is that IT is software these days; it’s all code. Massive, detailed upfront designs are not needed to get started with software, which doesn’t mean that upfront designs are not needed at all. But we can start small, with a minimal viable product (MVP), and then iterate to the eventual product. There will always be a request for a first architecture or a design.

But what is architecture then? Learn from architect and author Gregor Hohpe: architecture is providing options. According to Hohpe, agile methods and architecture are ways to deal with uncertainty and that leads to the conclusion that working in an agile way allows us to benefit from architecture, since it provides options.

That’s what this book is about: options. Options in cloud providers, the services that they provide, and how businesses can use these, starting with the next chapter, about defining the multi-cloud strategy for businesses.

Summary

In this chapter, we learned what a true multi-cloud concept is. It’s more than a hybrid platform, comprising different cloud solutions such as IaaS, PaaS, SaaS, containers, and serverless in a platform that we can consider to be a best-of-breed mixed zone. You are able to match a solution to a given business strategy. Here, enterprise architecture comes into play: business requirements lead at all times and are enabled by the use of data, applications, and, lastly, technology. Enterprise architecture methodologies such as TOGAF are good frameworks for translating a business strategy into an IT strategy, including roadmaps.

We looked at the main players in the field and the emerging cloud providers. Over the course of this book, we will further explore the portfolios of these providers and discuss how we can integrate solutions, really mastering the multi-cloud domain. In the final section, the organization of the transformation was discussed, as well as how the role of the architect is changing.

In the next chapter, we will further explore the enterprise strategy and see how we can accelerate business innovation using multi-cloud concepts.

Questions

- Although we see a major move to public clouds, companies may have good reasons to keep systems on-premises. Compliance is one of them. Please name another argument for keeping systems on-premises.

- The market for public clouds is dominated by a couple of major players, with AWS and Azure being recognized as leaders. Name other cloud providers that have been mentioned in this chapter.

- We discussed TOGAF as an enterprise architecture methodology. To capture business requirements, we studied a different methodology. What is the name of that methodology and what are the key components of this methodology?

- IaaS, PaaS, and SaaS are very well-known cloud service models. What does CaaS refer to typically?

Further reading

- Every business is a software business by João Paulo Carvalho, available at https://quidgest.com/en/articles/every-business-software-business/

- Multi-Cloud for Architects, by Florian Klaffenbach and Markus Klein, Packt Publishing

Join us on Discord!

Read this book alongside other users, cloud experts, authors, and like-minded professionals.Ask questions, provide solutions to other readers, chat with the authors via. Ask Me Anything sessions and much more.

Scan the QR code or visit the link to join the community now.

https://packt.link/cloudanddevops