Chapter 1: An Introduction to IAM and AWS IAM Concepts

Identity is the perimeter of security, and every transaction, capability, administrative event, and infrastructure component of cloud providers such as Amazon Web Services (AWS) ultimately depends upon identity services to govern all its capabilities. If that scope wasn't large enough already, tying AWS' native capabilities to an existing enterprise, customer, administrative, or infrastructure identity deployment can seem so complex as to make it difficult for cloud identity administrators to know how or where to start. This book will help you overcome the paralysis caused by the capabilities of the platform by approaching the implementation of AWS IAM (IAM) in a use case driven fashion, informed by real experiences working in large enterprise AWS environments.

By the end of this chapter, you will be familiar with the foundational concepts of IAM and see how they are applied within an organization. You will learn the purpose of the AWS IAM service, its components, and how they all work together to secure access to AWS resources. Finally, you'll use the AWS Management Console to create and manage AWS IAM resources, including IAM users, groups, and policies.

This chapter will cover the following topics:

- Understanding IAM

- Exploring AWS IAM

- Putting it all together

Understanding IAM

Identity is the most granular unit of security. The users, services, and systems that interact with infrastructure, applications, APIs, and endpoints must all be identified, authenticated, and authorized in order to perform their functions. The AWS platform operates under a rigid identity-centric model. Bridging that model with your own organization's identity implementation can be daunting.

Identity practitioners can (and do) argue about the minutiae and nuances of the terminology used within IAM. However, for our purposes, we can afford to use a broad definition of IAM in AWS:

For something purported as a simple definition, that sure is a mouthful. However, if we break the statement down into its constituent components and consider a typical use case, it affords us an opportunity to see how many technical disciplines you may already be familiar with that relate to IAM:

In layman's terms, we have these digital accounts that can be used to access computer systems. These accounts either directly or indirectly map to a person. This means that the account is either a digital representation of that person or the person owns and controls those accounts. That person can demonstrate proof of control of those accounts and is accountable for actions taken with those accounts. And those accounts have a life cycle, meaning under certain conditions they are created, under other conditions they may change, and at some point, they may eventually cease to be.

This is called identity management. Identity management is responsible for the following:

- Keeping accounts up to date

- Keeping downstream consumers of those accounts synchronized with the authoritative sources that define the account

- Provisioning and deprovisioning accounts entirely from various data stores

In short, it's a collection of processes responsible for managing account life cycle events in accordance with business, legal, or technical controls. These controls trigger life cycle events for accounts, such as account creation, modification, and disablement. What those life cycle events are will vary depending upon the event, type of account, business, and requirements of the system using those identities.

Now, let's look at the rest of the definition:

Those accounts, having been created, can be used to execute specific activities. What they can do is determined by rules and policies. In order to do anything, the account must first provide proof that whoever or whatever is using it to perform an activity is actually allowed to do so. That proof comes through a shared secret that validates the authenticity of the actor behind the account. This second part of our IAM definition addresses something called access management. Access management addresses the authentication of the account (proving you are who you say you are) and the authorization of that account (proving that you are allowed to do what you are trying to do with that account) to access resources or to perform certain tasks in accordance with established policies.

IAM applied to real-world use cases

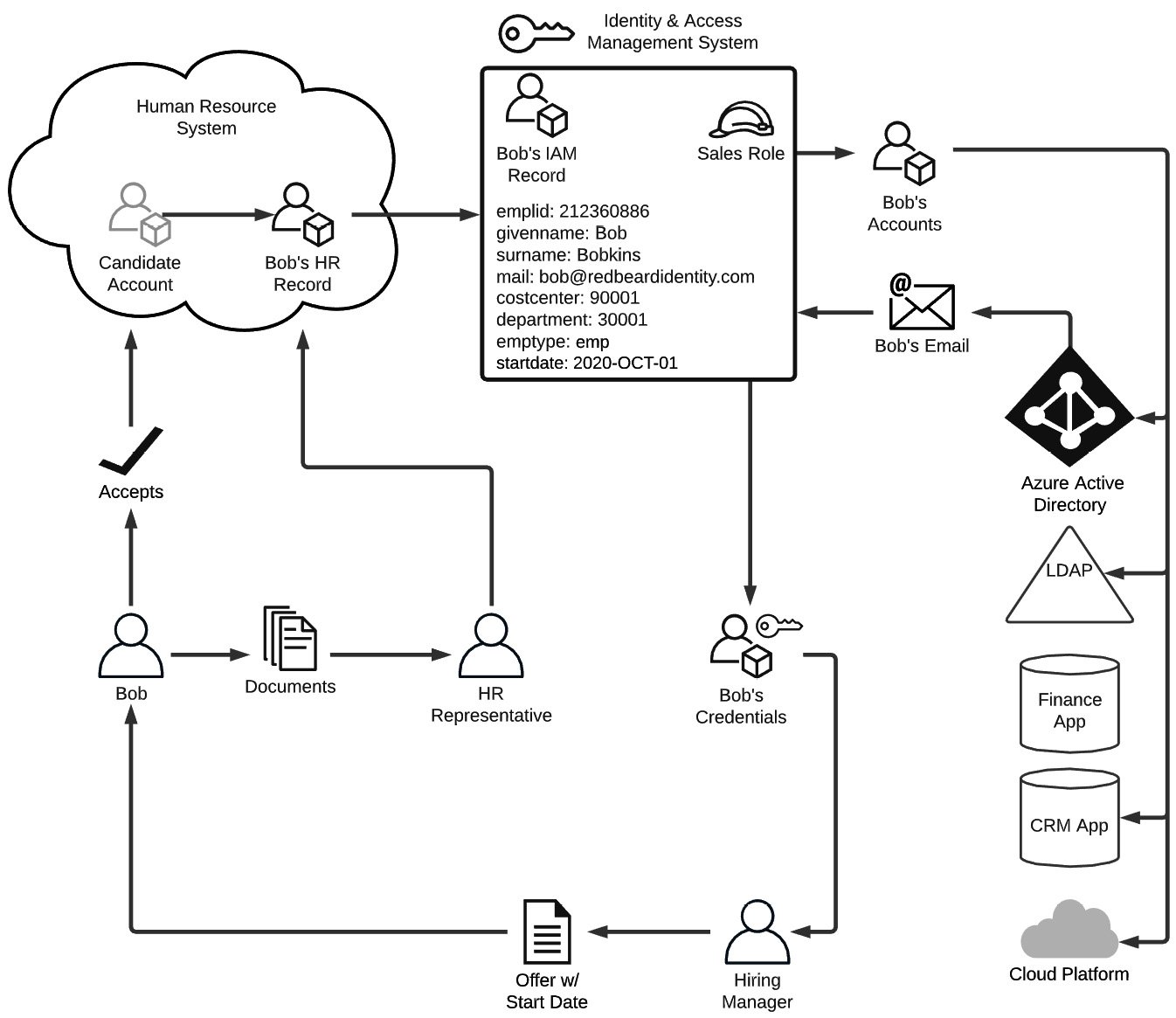

To understand this better, and to provide a flimsy pretext to introduce some additional concepts that are not so easily derived from that definition of IAM, let's imagine what happens when someone joins a new company. To help visualize all the actors, systems, and life cycle events in play, take a look at the diagram in Figure 1.1.

In this example, Bob has applied for a sales role at a large identity services organization called Redbeard Identity, which has a reasonably mature internal IAM program, application portfolio, and cloud platform capabilities. Bob's identity experience actually began long before he got to the point where the hiring manager was prepared to make an offer, because in order to apply for the position, he had to create a profile inside of Redbeard Identity's candidate management system.

Important note

The Redbeard Identity organization will be the organization referenced for several use cases and scenarios throughout this book. Whereas real organizations typically have a fixed enterprise architecture, we will adjust the architecture, capabilities, services, user accounts, and other characteristics of the Redbeard Identity organization from chapter to chapter in whatever ways we need to best demonstrate the material of that chapter. Please don't be confused if our example organization's characteristics are not entirely consistent throughout the book.

This marks the first identity life cycle event in Bob's onboarding journey: user account creation. Bob, as a user of the candidate management system, is providing self-issued, unverified information about himself such as his name, contact information, and details about his work history. As there is neither external proof nor an outside source of control validating the information he enters into this system, his candidate account is considered a low-assurance record. As long as Bob remains merely a candidate for the sales role, that low level of assurance is sufficient for the purpose that the candidate record system account serves:

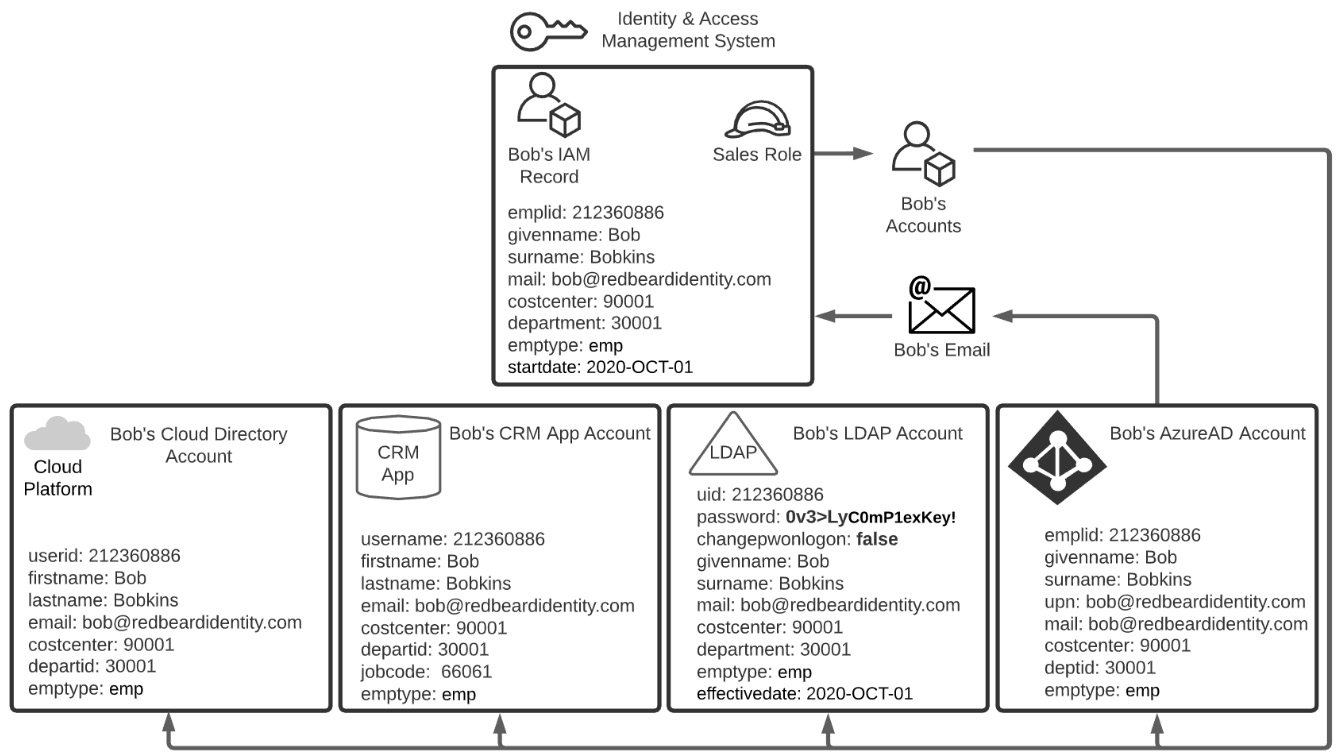

Figure 1.1 – Example of IAM life cycle events and flows

Bob knows his craft well, is an impressive salesman, and aces his interviews. After the details are agreed upon, the hiring manager sends Bob the offer letter confirming the details of his role, along with instructions for accepting the offer. Bob accepts by signing into the candidate portal and accepting the job offer. Now that Bob is more than just a candidate, the authenticity of the details that Bob provided when populating his candidate account must now be verified. To ensure that he is who he says he is, the HR representative will start a process called identity verification. This process is defined by the US Department of Commerce's National Institute of Standards and Technology as a process ''to ensure the applicant is who they claim to be to a stated level of certitude'' (NIST Special Publication 800-63A, Digital Identity Guidelines, Section 4, NIST).

The HR representative asks Bob to provide some identifying documents to facilitate his onboarding and help corroborate the information that he already entered as part of his candidate profile, such as a copy of his passport, a state-issued identification card, and his tax information. For the sake of argument, let's just say Bob hands the HR representative these documents in person to ensure that Bob himself has been compared against these artifacts. Thus, he sidesteps any concerns about him stealing valid credentials from someone else to use in his efforts to secure employment. The HR representative will finally validate these artifacts against their authoritative sources to ensure their authenticity, proving that Bob really is who he says he is. With the confidence that Bob is Bob and that the information Bob entered into the candidate management system is accurate, the HR system creates Bob's employee record and sets it to become active on Bob's start date.

As we said earlier, this organization has a reasonably mature IAM program. As part of a nightly process, the IAM system checks the HR system for any discrepancies in the data between the records stored there and its own corresponding identity records that it maintains in order to keep them in sync. When a change is made to an existing HR record that has a corresponding identity record, such as in the case of an employee changing departments, the department attribute on that employee's identity record also gets updated with the new department value. This is an example of attribute and metadata synchronization being used to ensure the consistency of identity data across data stores. In this case, the HR system is acting as an authoritative source for the IAM system, meaning that the records, attribute values, and other information from that system will overwrite any changes made directly against the records in downstream systems.

This organization uses business logic that tells the IAM system to create new identity records for new joiners one week from the start date listed on the new joiner's HR record. Once Bob's start date is less than a week away, that logic triggers the IAM system to provision, or create, his identity record. This will be the authoritative account record for all downstream systems, which in turn look to the IAM system as their own respective authoritative source. The IAM system will create Bob's identity record based upon an established pattern of attributes and characteristics, or a schema. It contains certain attribute types and values based upon the kind of account that Bob's identity record is. In Figure 1.1, we see a sample of (an admittedly spartan) schema for Bob's identity record. Let's pretend that we can actually take a look at the identity schema for Bob's record within the IAM system using Table 1.1:

Table 1.1 – Sample schema record for Bob within the IAM system

This shows us the attribute names, their current values, and the authoritative sources for each of the attributes in this schema. You'll notice that for the most part, the HR system provides the bulk of the authoritative data for the attributes, with the exception of ''mail,'' which is currently null (or without a value), and which also uses Azure Active Directory (AD) as its authoritative source.

You aren't constrained to a single authoritative source for your identity schema. In fact, you can have nearly infinite combinations of conditional clauses, secondary sources, and compound sources when defining your schema and the authoritative sources used to populate the schema's attributes. Beyond that complexity, you can also have several distinct schemas depending on the type of identity you are defining. We've only been examining Bob's identity journey as he gets onboarded at Redbeard Identity, and he is an employee as denoted by the emptype attribute. Contractors will likely have distinct schemas, as will bot process automation accounts, service accounts, business-to-business accounts, and customer accounts. But to keep things simple, we will stick with Bob the employee.

Bob works in sales, but it is doubtful that Redbeard Identity is a pure-sales organization given that they have enough technical wherewithal to run their own IAM infrastructure. Even if they were that operationally lean, there are regulations that demand evidence that some workers with certain job responsibilities cannot perform other, complementary responsibilities in order to reduce the risk of malfeasance. The go-to example for this is the protection control between accounts receivable and accounts payable in financial services organizations in order to prevent someone entitled to issue invoices from also approving their payment.

Separation of duties requires more than one person in order to complete a business task. Organizations implement separation of duties by applying technical controls that restrict or enable what a person can do based on business and regulatory requirements. Those rules, restrictions, and permissions are called policies, and a collection of policies that grants somebody the full range of access that they are entitled to depending upon their responsibilities is called a role. Aligning policies to roles, and roles to users through attributes or business logic is one part of access management. Providing evidence that those controls function as designed and comply with business and regulatory requirements is identity governance and audit. Identity governance and audit, access management, roles, and policy, all work to ensure that Bob will only be able to access the systems and resources that are appropriate for him to access, or in other words, that he is authorized to access.

This ''all or nothing'' approach to access is an example of coarse-grained authorization. Here, access is determined on a seemingly binary ''yes/no'' level based on the role that Bob was assigned provisioning him an account in the system. In Bob's case, he received the Sales role because, as we've said more than a few times now, he works in sales. However, there was no attribute labeled ''role'' that indicated which role he would be assigned. And there doesn't need to be. The logic that determines which entitlements get applied to an identity upon creation can vary wildly. In this scenario, Redbeard Identity's IAM system assigns roles based on the combination of the ''costcenter'' and ''department'' attributes. There could also be application-level roles and policies that provide fine-grained authorization to certain application-specific functions.

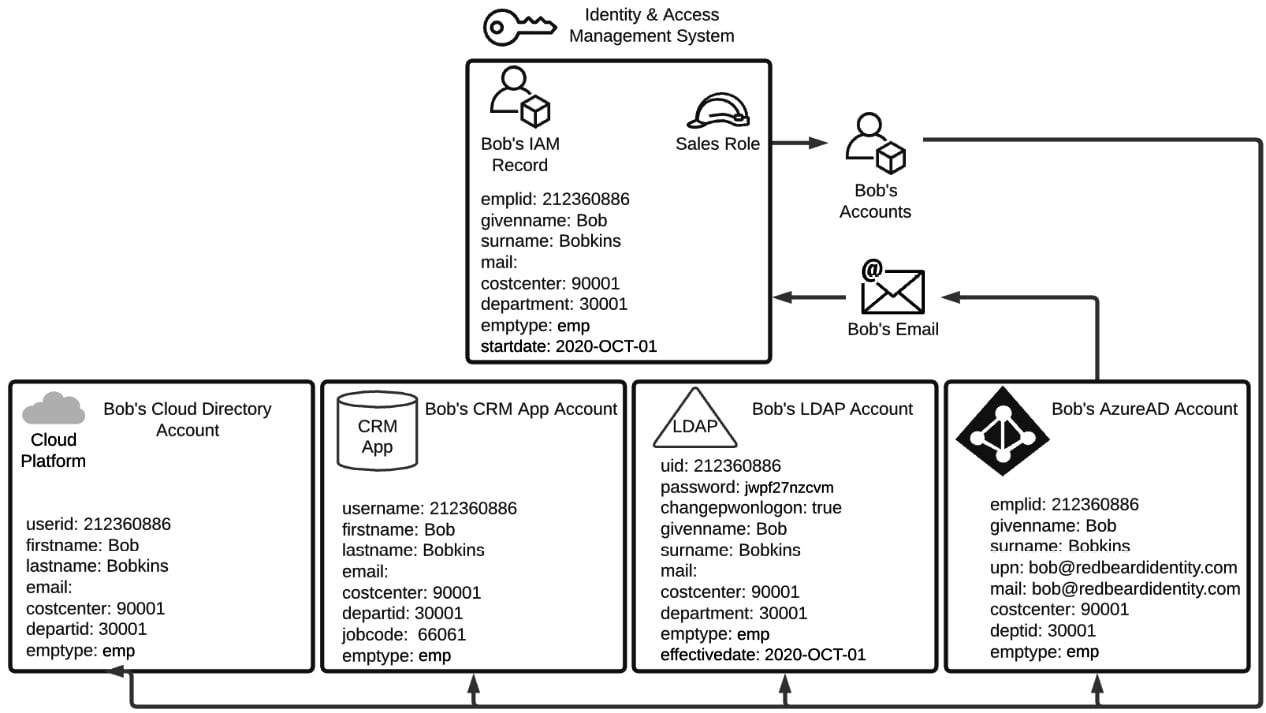

Now that Bob's identity has been provisioned and the IAM system has determined what role aligns to that identity, the next step is for the IAM system to begin provisioning Bob's accounts in the various downstream systems that he is entitled to access. Users with the Sales role get certain birthright entitlements, which are accounts and access that everyone gets just by being active employees within Redbeard Identity with that basic Sales role. Figure 1.2 shows the provisioning process from the IAM system into these account stores in greater detail, with information about the schema for each of the accounts that Bob will be getting:

Figure 1.2 – Different account schemas across different identity stores

The IAM system provisions the following:

- Bob's Azure AD account

- An LDAP account in the company's directory

- A user account in Redbeard Identity's customer relationship management system where Bob will be spending most of his workdays

- An account in the cloud directory used by Redbeard Identity's cloud-hosted applications

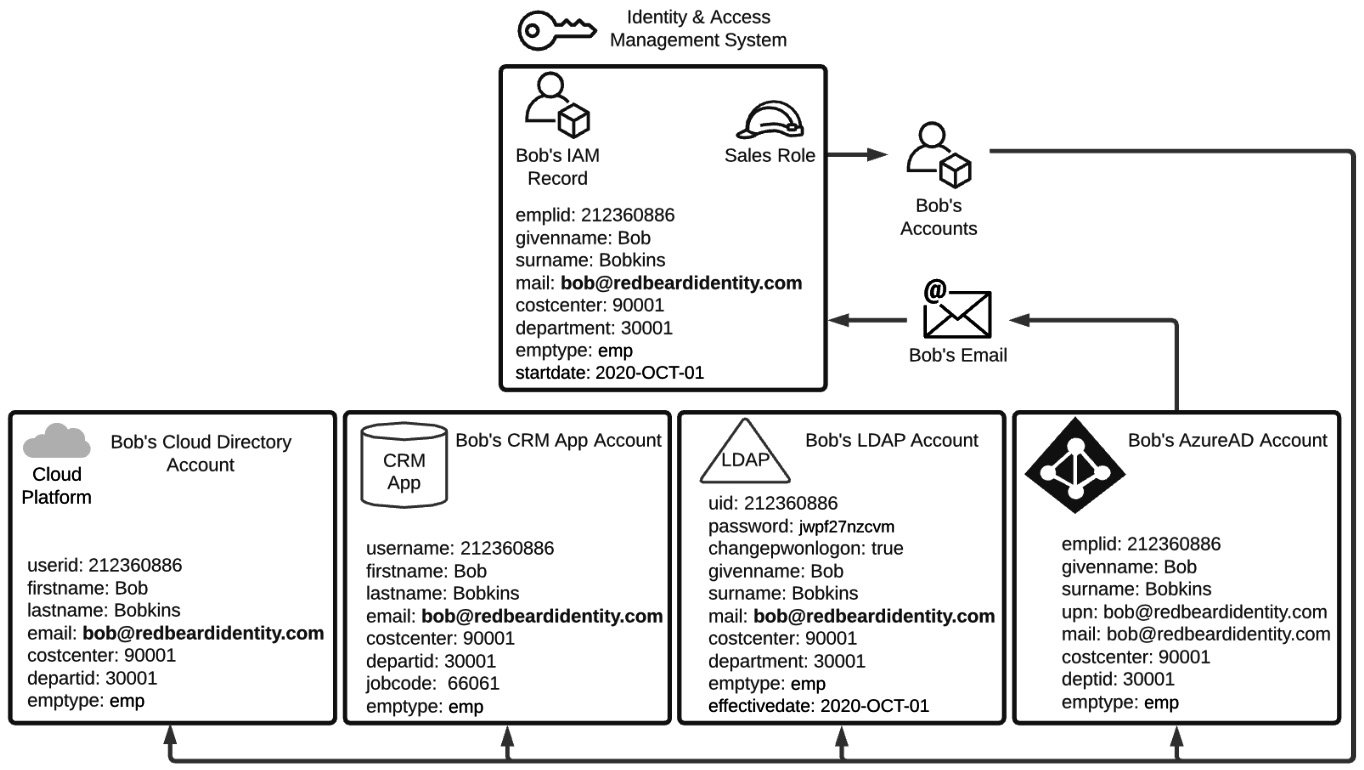

Each one of these account stores is an example of an identity store. This is the place where an application or system can store its own instance of Bob's account with all the application-specific attributes added on. Just like how the HR system was the authoritative source for the IAM system, the IAM system is the authoritative source for these accounts and for many of the attributes within these identity stores. Now that Bob has an Azure Active Directory Account, he can get a mailbox and email address. If you recall from Table 1.2, Bob's main identity record did not have a value under the mail attribute when it was first provisioned. It is only now that the IAM system will detect Bob's email address when checking Azure AD for any new account updates. Upon detecting the discrepancy between the null value for the mail attribute in the identity record it has for Bob and the email attribute it reads on Bob's Azure AD account, the IAM system imports that update into Bob's IAM record with the new information obtained from that authoritative source. But the updates don't stop there! Look at Figure 1.3:

Figure 1.3 – Account attribute synchronization across authoritative sources

Remember that the IAM record itself is an authoritative source for several of the attributes on the downstream accounts that were provisioned as part of Bob's Sales role. In this instance, Bob's LDAP, CRM, and Cloud Directory account will each get Bob's new email address value written to the attribute that each has mapped to correspond to the IAM record's mail attribute value. Now that Bob has all of his accounts provisioned and synchronized with their authoritative sources, Bob is poised to be productive on his first day on the job.

That is to say Bob could be productive, assuming he knew how to identify himself as the owner of the account in each of these systems. This takes us to the last life cycle event depicted in Figure 1.1, which is the issuance of Bob's credentials. Credentials are the evidence used to attest that the person accessing a resource is who they say they are.

When talking about user accounts, credentials most often take the form of a unique identifier (such as a username) and a shared secret. This shared secret is between the person attempting to access a resource and the system that is trying to validate the identity of the person attempting to access a resource (such as a password). Bob's username plus his account password are his credentials to access these Redbeard Identity systems. Let's take a look at how that credential was created and delivered to Bob, as well as how the downstream applications can also verify Bob's identity despite not necessarily needing to maintain a set of their own for Bob to use.

Within Redbeard Identity, the mechanics of creating Bob's credentials are fairly straightforward. As part of the initial account creation process, the IAM system generates a random password to use as the password value on Bob's account. As you can see in Figure 1.3, though the password was generated by the IAM system, the IAM system is not acting as the authoritative source for the password, nor is it even storing the password attribute in its main identity record for Bob. Looking more closely at the schemas on those downstream accounts, we see that the only system that stores Bob's password value (or some form of hash of this value) is the LDAP directory.

In addition to being the only place where that value is stored, there is another unique attribute on that LDAP account called changepwonlogon, which is currently set as true. When the changepwonlogon value is set to true, it will force the person who entered the username and password to enter a new value for the password. When changepwonlogon is false, the person who correctly enters the account's username and password will simply be permitted to access the system or resource they were attempting to access when challenged for their credentials.

Providing the credentials is how a user can authenticate themselves, or how they prove that they are who they say they are. As Bob can't receive that initial password directly from Redbeard Identity's systems since he does not have access to Redbeard Identity's network yet, the IAM system instead issues the first password for Bob's account to Bob's hiring manager.

So why isn't the password written into all of the other identity stores where Bob has an account? In the specific situation we are examining using Bob's onboarding into the Redbeard Identity organization, they are maintaining a single authoritative identity store for all of their application authentication. This means that Bob will use a single, centrally managed username and password to access the applications and systems he needs to use to perform his job. This is as opposed to a system where he would be required to memorize a unique username and password stored and managed by each individual application. This is single sign-on (SSO).

Applications maintain application-specific user records for each user that they use for their own purposes (such as authorization). However, the application delegates authentication to a central identity store using a directory services protocol such as LDAPS or Kerberos, or in the case of many modern web apps, a federated web-based protocol such as SAML or OpenID Connect. Using SSO reduces the number of credentials and the locations where those credentials are stored. This reduces the attack surface that a malicious actor can try to exploit to steal a credential. Using SSO also helps keep Redbeard Identity workers happy since they only have one password to manage.

Bob's first day at Redbeard Identity arrives. He shows up at the office for new hire orientation, receives his laptop, and his hiring manager shares the initial password for his account with him so he can sign into his account. After his credentials are validated, the changepwonlogon attribute triggers the life cycle event responsible for ensuring that the initial password gets changed. Bob enters a new password.

Once that is accepted and written to his LDAP account, the changepwonlogon value flips to false, and Bob becomes the sole owner of his account, which is essential for non-repudiation. From now on, any actions logged under emplid can be tied solely to him since he is the only one who can access resources and applications by authenticating using those credentials. And with that, Bob's identity onboarding experience is complete:

Figure 1.4 – Bob takes ownership of his account

Now that Bob has his account, he needs to sign into the applications he will use to perform the majority of his job duties. As we mentioned earlier, the Redbeard Identity organization maintains its users' passwords exclusively in its LDAP directory. Though Bob has accounts in the user stores of other systems and applications, those applications have delegated their user authentication to that LDAP directory. Applications can perform lookups and password validations directly against the LDAP using LDAPS, but that model has constraints that limit its usefulness as a modern authentication pattern.

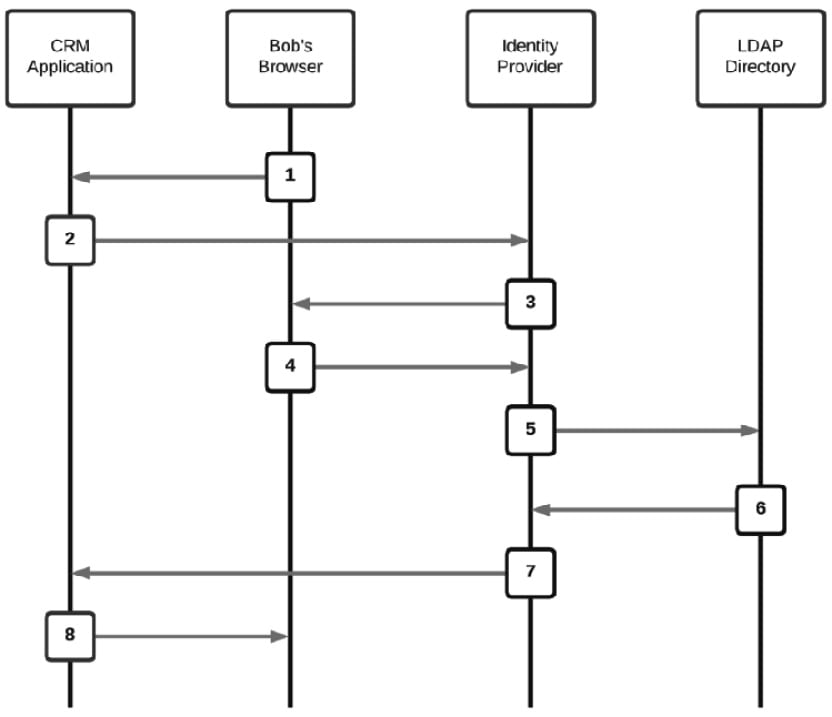

Modern applications should rather use identity federation for user authentication, which is a model where the application looks to an external identity authority to receive trusted identity information. The CRM application that Bob will be spending most of his time in uses identity federation to authenticate its users. The process for the CRM app receiving an authentication token for Bob's identity from the identity provider is shown in Figure 1.5:

Figure 1.5 – Federated authentication transaction using an identity provider

- From a browser, Bob goes to the CRM application.

- Since Bob doesn't have a session cookie, the CRM application redirects the browser to the Identity Provider that it uses for user authentication.

- The Identity Provider redirects Bob's browser to a logon form to collect Bob's username and password.

- Bob's username and password are posted to the Identity Provider.

- The Identity Provider performs the password validation on Bob's account against the authoritative source it uses for authentication – in this case, the LDAP directory where the Redbeard Identity organization stores its user credentials.

- The LDAP directory responds that the credentials are valid and may optionally send along some additional attributes that the CRM application may need to reference at authentication time.

- The Identity Provider creates a signed authentication token using its private signing certificate and posts that to the CRM application. The CRM application is assured that Bob has been authenticated by the external Identity Provider due to the unique cryptographic signature on the authentication token.

- The CRM application looks at the subject of the authentication token, which in this instance is the

emplidfrom the LDAP directory, and matches it to its local account under that sameusernamevalue. The CRM application examines its local user record for Bob for hisjobcodevalue to determine what application role he can assume. Job code66061corresponds to a sales representative role. The CRM app establishes an application session for Bob under that authorization context, and Bob is now logged in.Important note

It is important to remember that the example we just walked through was meant to highlight IAM concepts, not necessarily IAM architecture or engineering best practices. Organizations' IAM and security maturity can vary greatly as they balance the risk equation of facilitating their core business against the monetary and opportunity costs of identifying and remediating potential security threats.

The Redbeard Identity scenario has provided us with an example of IAM principles in action and shows how the various components of the IAM system combine to form a platform that facilitates business outcomes and secure organizational resources. Now that we have an idea of what an IAM is, let's begin our exploration of it within AWS.

Exploring AWS IAM

''Wait,'' you may be saying, ''I thought this book was supposed to be about AWS IAM? What's the deal with the overwrought organizational identity scenario I just spent the last several pages reading? When do we get to the AWS stuff?'' AWS is a cloud provider that is ultimately governed by identity. AWS environments are owned by Amazon accounts and organizations, and each of the resources created within those environments has life cycle events governing its creation, modification, and eventual termination.

Additionally, the scope and scale of what someone or something can do with those resources are governed by identity, access management policies, and delegated authorization models. Where organizations and technologists encounter difficulty is in understanding the how, what, and why of AWS in the context of identity in light of its rich, and seemingly overlapping, infrastructure-as-a-service and platform-as-a-service components.

Taking a moment to recontextualize your organization's use of AWS through the lens of identity, and especially in the context of the business, security, and governance challenges you may have already solved in on-premises infrastructure in ways similar to the Redbeard Identity scenario, will aid us as we demystify this seemingly complex topic.

According to Amazon (What is IAM?, at https://docs.aws.amazon.com/IAM/latest/UserGuide/introduction.html),

This reads very similarly to our initial, high-level definition of IAM that we outlined in Understanding IAM. AWS IAM creates and manages the accounts used to sign in to the AWS Management Console and handles credential management and strong authentication capabilities for the accounts it manages.

Access management and authorization for users, services, and even resources, including fine-grained authorization to AWS resources, are managed through access policies that are defined, governed, and validated against AWS IAM. Governance, compliance, and audit are also reported through AWS IAM and presented through other AWS services. AWS IAM and its supporting identity security services offer a complex and feature-rich IAM capability for administrating and controlling who has access to what and under what context that access is authorized.

IAM for AWS and IAM on AWS

AWS IAM is not the only tool that is capable of providing IAM services inside of the AWS cloud. As we saw in the Redbeard Identity scenario, a comprehensive IAM solution at an organizational level is composed of several different systems and services. These fulfill the business and security use cases required for that business. There is not a monolithic ''Redbeard Identity IAM Service.'' Rather, it is a mix and match of various provisioning, governance, authentication, and directory services.

AWS IAM is the service to govern access to AWS services, but there are several other services that can be mixed and matched in pursuit of solutioning business IAM challenges. When speaking about AWS IAM, we are referring to IAM for AWS, specifically in the context of AWS as infrastructure-as-a-service. When we use other AWS services to solve IAM challenges, we are applying IAM on AWS and using those services in the context of AWS as a platform-as-a-service. We will address what some of those other services are and their use cases in later chapters.

Tip

AWS IAM provides identity services for AWS as an infrastructure-as-a-service platform. Other AWS identity services provide identity capabilities for AWS as a platform-as-a-service.

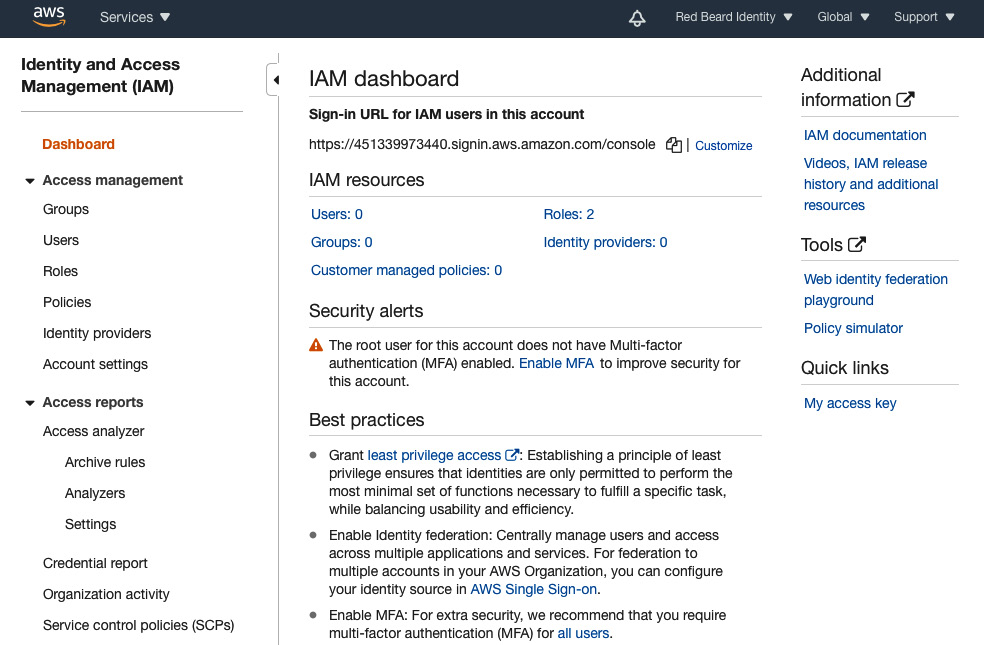

The AWS IAM dashboard

With so much capability, it can be difficult to see how all the pieces fit together, let alone figure out how to mash all of those pieces together in order to develop solutions to identity challenges in the cloud without first familiarizing yourself with the tool directly. Let's start by taking a quick look at the tool as it appears from inside of an AWS environment:

Figure 1.6 – AWS IAM dashboard

The center panel offers a single-pane-of-glass scoreboard for the counts of critical identity objects that are live in the environment. Already, you may recognize some of the IAM terms and concepts that we touched upon in the Redbeard Identity organization example earlier in this chapter, particularly roles, users, and policies. In the context of AWS, each of these terms has a specific definition, which we will discuss in more detail momentarily.

Links to the individual administrative panes for Groups, Users, Roles, Policies, Identity providers, and Account settings are on the left side of the AWS IAM dashboard. Each one of those links will allow you to individually view and administrate the components.

Further down, we have some reports and analytics tools designed to facilitate policy administration and aid in the creation and audit of policy structures. They govern access to AWS resources in the environment. The Credential Report details the status and age of the credentials for every AWS IAM user managed by the environment. Finally, the Organization activity and Service control policies (SCPs) sections are special administrative sections. They are only activated when an AWS account is part of something called an AWS organization. This is a construct that allows large organizations to govern multiple AWS accounts in line with a single, centralized policy.

Principals, users, roles, and groups – getting to know the building blocks of AWS IAM

In case you couldn't tell, we are already experiencing some namespace collision on the terms we used earlier to describe Bob's onboarding and authentication journeys at Redbeard Identity and those used within AWS. For example, we could get away with interchangeably referring to ''Bob's identity record'' and ''Bob's identity'' in the example. The definitions used when referring to the components that compose and interact with AWS IAM have very specific definitions. You will need to understand that taxonomy to ensure you understand how AWS IAM, and AWS as a platform at large, operates. The following definitions are taken from the AWS IAM User Guide (https://docs.aws.amazon.com/IAM/latest/UserGuide/intro-structure.html#intro-structure-terms):

- Principals: A person or application that uses the AWS account root user, an IAM user, a federated user, or an IAM role to sign in and make requests to AWS.

- Entities: The IAM resource objects that AWS uses for authentication. These include IAM users, federated users, and assumed roles.

- Identities: The IAM resource objects that are used to identify and group. You can attach a policy to an IAM identity. These include users, groups, and roles.

- Resources: The user, group, role, policy, and identity provider objects that are stored in IAM. This can be an action in the AWS Management Console or an operation in the AWS CLI or AWS API.

To ensure topical clarity moving forward, we will be using the AWS definitions of these terms unless a distinct definition is specifically referenced in context. Speaking of topical clarity, those definitions are far from clear. A principal authenticates with an entity, but is that entity considered an AWS identity? An identity can be an AWS IAM role, user, or group, and an entity can be an AWS IAM user or role, but can both of them have an access policy attached to them? Both entities and identities are resources, and both entities and identities can be roles or users, but are roles and users themselves resources? Perhaps it will make things easier to approach these definitions with an old-fashioned Venn diagram. Take a look at Figure 1.7:

Figure 1.7 – The relationship amongst AWS IAM principals, entities, identities, and resources

Let's start with the circle that's all by itself, Principals. The best way to think about Principals is in terms of the subject of a sentence, or the who or what that performs the action in the sentence's predicate. In the case of AWS, individual users act as principals when they sign into their AWS IAM user accounts. However, principals don't have to be tied to a flesh-and-bone person.

Consider service accounts, bot process automation accounts, or even programmatic access when calling APIs – each one of those use cases acts as the principal when either signing into a corresponding account or assuming a delegated role that permits that service to access a resource. What's more, other AWS services, such as S3 or EC2, may assume a service-level role to act as principal and authenticate and get access to manipulate resources.

On the topic of resources, resource is a very broad term in AWS. In this particular AWS IAM context, it refers specifically to all of the things stored and managed in AWS IAM that appeared on the at-a-glance dashboard on the landing screen of AWS IAM we saw in Figure 1.6, such as users, groups, and roles. If you create it in AWS IAM, it is an AWS IAM resource. Similarly, S3 bucket objects are resources within the S3 service. In the broader context of AWS as a platform, a resource is an object created and managed within an AWS service in an AWS environment.

That is also the reason why both entities and identities are fully encapsulated within the resources circle in the diagram, as they both only exist in the context of AWS IAM. The entity is the AWS IAM resource that a principle uses during authentication, and as such provides information about the principal through policy objects attached to that IAM user, assumed role, or federated user. If entities can be described as AWS IAM resources used by a principal during authentication, then identities are the corresponding resources assumed by principals for authorization.

Since identities cover users, groups, and roles under the auspice of grouping and identification, this means that the foundation for authorization decisions within AWS IAM are actually the user, groups, and role identity resources. The two act in conjunction when a principal is engaged with the service, with the entity as the surrogate for the principal within AWS IAM correlating the principal to an authenticator or credentials, and the user identity's attached policy supplies the information for AWS IAM to determine what that principal is and isn't allowed to do:

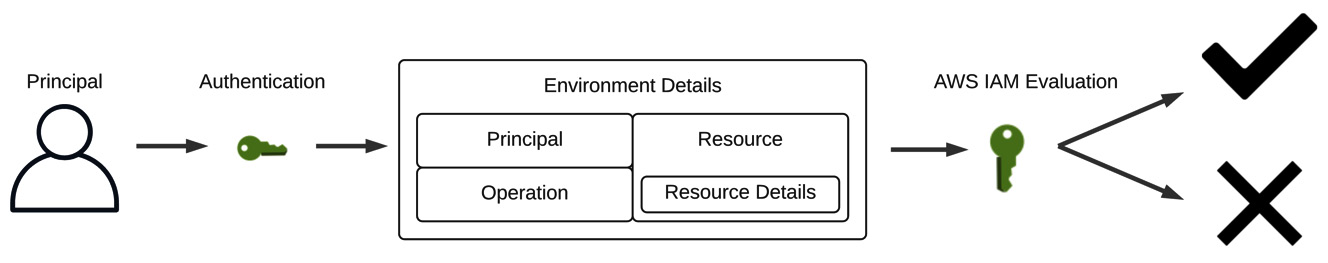

Figure 1.8 – AWS IAM evaluates principal authentication and request context to permit or deny actions on a resource

But how does AWS IAM decide what the principal can and cannot do? AWS IAM evaluates each request in light of a request's context, which is to say a combination of characteristics that can be evaluated against a policy. Take a look at Figure 1.8 to see a breakdown of what contributes to a request's context. AWS IAM considers who is attempting to take action, or the principal. Any time that principal interacts with the AWS Management Console, they are performing operations against resources.

The AWS IAM service has about 40 specific operations that a principal can perform against its resources. For the most part, they align with the familiar CRUD acronym, (create, read, update, delete), but the actions specify the AWS IAM resource targeted by that operation in the operation name, for example, create-user, update-group, get-role, delete-policy. Further details about a specific resource that will be the target of the operation narrow the scope of action further. Finally, there are the environmental details in which the request takes place, such as the time of day or originating IP address.

AWS IAM considers the full request context against the policy applicable to the principal's identity resource and decides whether the action is permitted or authorized, assuming the principal's entity has been sufficiently authenticated.

Authentication – proving you are who you say you are

In the Redbeard Identity scenario, we made several references to both ''verifying the authenticity'' of things, such as Bob's personal information, and ''authenticating'' that Bob really was the account holder entitled to access the CRM application by providing his password, a shared secret.

The first, while an authenticating activity, is identity verification. Identity verification ensures that the principal you are issuing credentials to really is who they say they are through the validation of that identifying information by an authoritative source. Conversely, proving possession of a shared secret or token to demonstrate ownership and control of an account in the context of gaining immediate access to a system with that account is authentication as we will refer to it from here on out.

As we briefly touched upon in the previous section, before any principal is permitted to take action on an AWS resource, they must first authenticate themselves through the AWS IAM service. The most common way to do this is with a username and password pair through the AWS Management Console.

We will discuss the differences between the root user and IAM users and best practices on securing and administrating your AWS administrative users in Chapter 3, IAM User Management. But not every principal is a human behind a keyboard. For other principals, such as applications requiring programmatic access where a username and password validation flow would not serve, there is also the option to authenticate via an access key ID and secret key ID. You have the option of granting either access type to new IAM users.

Authorization – what you are allowed to do and why you are allowed to do it

Truth be told, we've already discussed authorization at length throughout this chapter. AWS IAM's primary function is arguably making authorization decisions based upon a policy evaluation against a request's context. That said, we've mentioned ''policy'' several times without defining what it means both in the broader context of IAM and specifically as a component of AWS IAM.

Policies are rules that define a course of action. IAM policies are rules that determine whether a user or system can access or manipulate a resource based on their attributes, role, or security context. AWS IAM authorization policies are a variety of rules and evaluation logic that combine to determine whether a given request is authorized based upon the information present in its request context. We will be diving very deeply into the various policy types and the anatomy of AWS IAM's JSON-based policy structure in a future chapter, but the policies that may be evaluated based on a request's context include the following:

- Identity-based policies: These are inline policies that are attached to IAM identity resources, namely users, groups, and roles.

- Resource-based policies: These are inline policies that are attached to AWS resources, such as a policy on an S3 bucket that indicates what a specific principal can do with that specific bucket's contents.

- Permissions boundaries: A policy that sets limits on what a specific IAM user or role can do with a service or resource. This policy represents a ''boundary'' for the IAM user or role it is applied to, meaning that other policies outside of that boundary will not be respected.

- The organization's service control policies: A policy that is similar to permissions boundaries but applies to AWS accounts governed by that organization.

- Access Control Lists (ACLs): ACLs restrict the resources that principals from different AWS accounts can access within your AWS account. This policy is unique as it does not use AWS IAM's JSON-based policy structure.

- Session policies: Session policies create a hybrid policy that lasts only the duration of the principal's session based upon attributes programmatically passed during authentication time and an identity-based policy. This is an ''advanced'' policy according to the AWS IAM User Guide.

AWS evaluates all applicable policies based on the request context to determine how the request should be evaluated. Generally speaking, if the request context fails any evaluation criteria for any of the applicable policies, the entire request is rejected unless a policy includes an explicit ''allow'' statement.

The AWS IAM dashboard is the jumping-off point for applying identity to AWS services and provides administrators an at-a-glance view of the IAM objects that currently exist within their AWS account. Don't be intimidated by the flood of terminology, or the obtuse relationships between the various IAM objects and authorization policies. These things may be difficult to fully grasp right now as they are devoid of context. This will become clearer as we work through some examples of how IAM objects are governed by AWS IAM.

Putting it all together

Now that we've seen the AWS IAM dashboard, familiarized ourselves with the terminology used with the service, and examined the relationship between principals, entities, identities, roles, groups, and policies, let's create some AWS IAM resource objects using the AWS Management Console. In order to complete this exercise, you will need to sign up for an AWS account at https://aws.amazon.com.

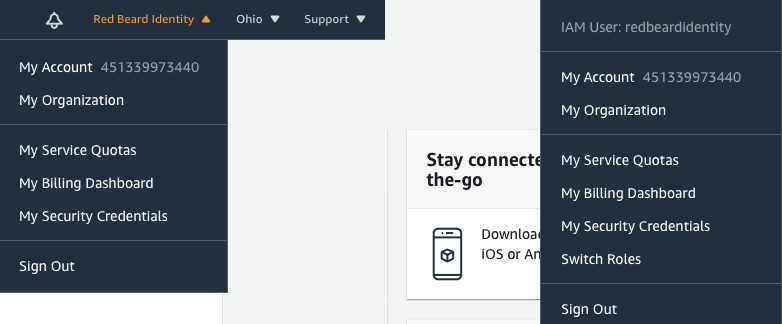

Signing in with the root user

If you have signed up with a new account, the first and only option you have to sign in to the AWS Management Console is with the Root user. The Root user is the owner of the AWS account, and similar to a root user in a Linux system, it is a super administrator with full access to all the services and resources available. Just as one would when configuring a server, we should only use the Root user for as long as it takes to set up a different administrative account to use:

- From the AWS IAM dashboard, expand Access management on the left and click on Users. From this screen, you can see every non-root user in your account, including important security information such as group membership information, access key age, password age, last activity, and whether or not that account has multifactor authentication enabled:

Figure 1.9 – AWS IAM user administration console

- As this is a new environment, our user list is empty. We create a new user by clicking Add user:

Figure 1.10 – User configuration and access type

- Let's name the new account

redbeardidentityand give it both programmatic access and AWS Management Console access. This means the account will be issued two sets of credentials, a password for console access, and the access key ID and secret key ID for use with the AWS command-line interface: - Since we will be using this account, we can select the option to populate our own password and uncheck the box that requires a new password on first login. If we were provisioning an account for another administrator, we would leave the ''password reset on first logon'' requirement in place to ensure that the other administrator was the only person who knew their password. Click on the Next: Permissions button:

Figure 1.11 – Permissions options

On the next screen (Figure 1.11), we see several options for granting permissions for the new account. Let's examine the options available to us. If this were a shared account with several different administrators performing different job functions, we could set up a group for each one of those job functions and attach policies to the group. Then by adding the new user accounts to the appropriate group, those users inherit the policies from the group. Alternatively, we could just copy the permissions from an existing user. This is a non-starter for our use case as we are currently creating the very first non-root user account in the environment and have no other account from which to copy permissions. Finally, we can create and attach a policy directly to the user. Since the wizard is selling groups as a ''best-practice way to manage users' permissions,'' we'll do that. This is also where we can optionally set a permissions boundary for this user. Since this user is an administrator, we don't need to set such a boundary:

Figure 1.12 – Create group and attach policy

- Clicking Create group takes us to the group creation screen where we can name the group and attach AWS-created policies to it. We also have the option to create our own custom policy for the group, but as the goal for this group is to grant full administrative privileges to the environment, and AWS already has a policy that grants those entitlements, we'll spare ourselves the administrative overhead.

- We give our administrator's group a name that will help ourselves and others recognize its purpose and click Create group:

Figure 1.13 – Create group and attach policies

The group is created, and we are returned to the user creation screen. The form now shows the new user as a member of the

FullAdministratorgroup. Click on the Next: Tags button. On the next screen, we can optionally create some tags to associate with this user. Tags are customizable attributes in the form of key-value pairs that you can define on nearly every resource object type in AWS, and you can use tags for reporting, searching, and perhaps most importantly, authorization policy. - Tags are powerful tools for governance, so we will define some

costcenterandjobcodetags and populate them with values that we may be able to use to define some session policies later. As we type, the console opens new rows for other tags. Type something like what is shown in Figure 1.14 and click on the Next: Review button:

Figure 1.14 – Attaching tags to the new IAM user

- After that, we can review all of our selections and create the user. Simply click on the Create user button and the operation is finished:

Figure 1.15 – Review and create the new user

The AWS IAM dashboard has been updated to reflect the new user and group creation, and the Users and Groups control panels now give us options to administrate the new IAM resource objects:

Figure 1.16 – Updated IAM dashboard

If we check the list of users, we see the new IAM user we've created, complete with an at-a-glance view of the group membership, the age of its credentials, its last activity, and whether it has multifactor authentication enabled:

Figure 1.17 – Updated IAM user administration console

- Now we can sign in using the non-root account. Note the Sign-in URL for IAM users in this account in Figure 1.16. It is an account-specific sign-in link for IAM users to use when signing into this particular AWS account so we will not need to memorize and enter the account number each time we sign in through https://aws.amazon.com:

Figure 1.18 – Root user on the left, IAM user on the right

Once signed in under the redbeardidentity IAM user account, and despite it having full administrator permissions to the AWS account just like the root account, we can see that it is an IAM user account based on the differences in the account information displayed in the menu bar.

Now that we've created our first AWS IAM user, let's recall once again why we bothered to do so in the first place. IAM is the discipline of managing the life cycle of digital accounts that correspond to and are under the control of a person and ensuring that only the correct resources are accessed by the correct actor at the correct time and under the correct context. Understanding how identity life cycle events and processes interact to achieve a specific business or technological outcome helps us understand how to achieve those same outcomes within the cloud. AWS IAM is the service that an AWS account uses to authenticate and authorize users and applications that use the account's services and handles the IAM use cases for AWS services.

AWS IAM controls IAM resource objects, including the entities that users, applications, or federated users use to authenticate themselves to the service. IAM users, roles, and groups are identity objects used to identity or group IAM resource objects for the application of authorization policy. AWS IAM assesses requests to take actions on AWS objects using the request context, which is a combination of details about the request, in conjunction with authorization policy objects that apply to the user, role, group, or resource that the principal is trying to manipulate. Each AWS account gets a root user, which is the superuser for the account. Best practice recommends that you use an appropriately scoped IAM user when accessing your AWS account, and not the root account.

Summary

Over the course of this chapter, we've learned the basics of IAM and seen it applied to a typical enterprise worker scenario. We also learned about the AWS IAM service, and how it applies IAM to AWS itself. Additionally, we learned about the types of objects managed by the AWS IAM service and got a high-level overview of how AWS IAM uses authentication, authorization, and request context to evaluate every request that comes into an AWS account. Finally, we took a tour of the IAM dashboard inside of the AWS Management Console and created our first non-root administrative user.

The next chapter will introduce us to an alternate method for interacting with our AWS account – the AWS CLI. We will learn how to install and configure it on Windows and macOS/Linux, including setting up different profiles for different use cases. We'll also examine the command syntax and get introduced to some tools that will help us discover command syntax and administrate objects. By the end of the chapter, we will have learned how to make programmatic calls to an AWS account.

Questions

- What is IAM?

- What is authentication?

- What is authorization?

- An IAM user, a role, a federated user, and an application are examples of what in an AWS service request?

- What are some examples of AWS IAM objects?

- How does the AWS IAM service decide whether a request to access a resource is permitted?

- Name the AWS policy types that can impact an authorization decision.

Download code from GitHub

Download code from GitHub